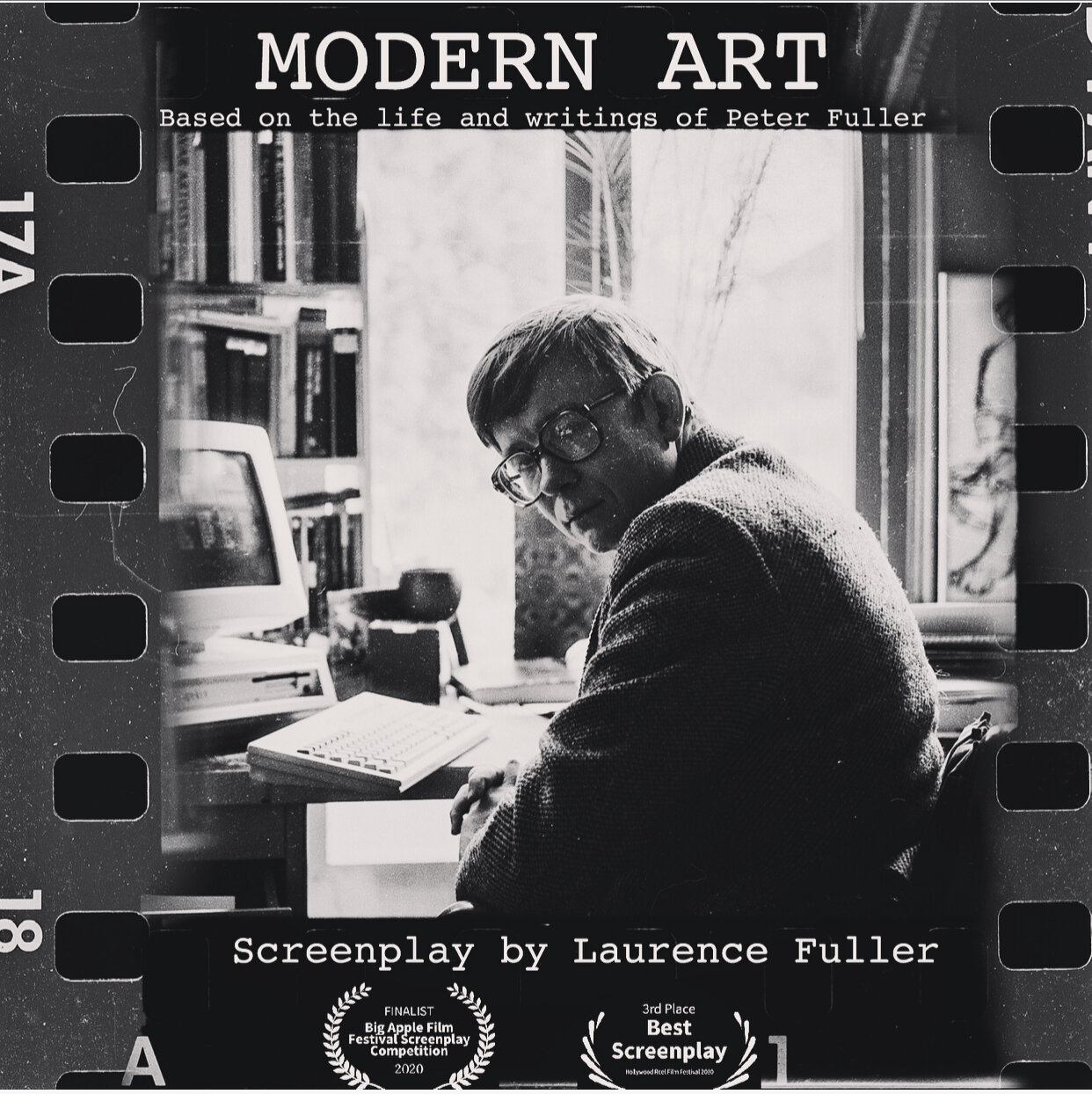

MODERN ART chronicles a life-long rivalry between two mavericks of the London art world instigated by the rebellious art critic Peter Fuller, as he cuts his path from the swinging sixties through the collapse of modern art in Thatcher-era Britain, escalating to a crescendo that reveals the purpose of beauty and the preciousness of life. This Award Winning screenplay was adapted from Peter’s writings by his son.In September 2020 MODERN ART won Best Adapted Screenplay at Burbank International Film Festival - an incredible honor to have Shane Black one of the most successful screenwriters of all time, present me with this award:

As well as Best Screenplay Award at Bristol Independent Film Festival - 1st Place at Page Turner Screenplay Awards: Adaptation and selected to participate in ScreenCraft Drama, Script Summit, and Scriptation Showcase. These new wins add to our list of 25 competition placements so far this year, with the majority being Finalist or higher. See the full list here: MODERN ART

The arts across the world are under attack right now, the telling comments by the likes of Rishi Sunak that artists should ‘re-train’, clearly show the administration’s priorities when it comes to supporting the arts at this time. I know that my father would have had a great deal to say about this. So you can read selected essays by Peter Fuller here on my blog during lockdown! I will be posting regularly.

FINE ART AFTER MODERNISM

by Peter Fuller, 1978

The London art community is very like a gymnasium. Every time you enter into discourse with your colleagues you first have to take a look around and see what posture everyone is adopting today. The collapse of the central, modernist consensus has led to exceptional enthusiasm among those who were once its High Priests for the volte-facing horse. For example, one critic, really quite recently, argued — and I quote — ‘the ongoing momentum of art itself’ is ‘the principal instigator of any decisive shift in awareness’. He dismissed all but a handful of ultra avant-gardists gathered around an obscure Paddington gallery as ‘obsolescent practitioners of our own time’. He assured us that the future would ‘overlook’ all but this minority he had identified.1 Thus he adopted the classical modernist position. Today, this same critic has spoken of his blinding experience on the road to Wigan; he is now urging upon us the joys and necessities of collaboration without compromise. I have never been of an athletic disposition : the sight of the vaulting-horse filled me with terror as a child, and it still does. Unfortunately, this means that those of you who have been following the overheated polemics and debates which have been going on within the art community, and in the art press, may therefore find many of my arguments, some of my examples, and especially my overall position, familiar. I can only apologize for my rheumatic fidelity to a position which expresses the truth as I perceive it. I hope you will bear with me.

When I was asked to come to this conference to discuss the artist’s ‘individual’ and ‘social’ responsibilities under the rubric, ‘Art: Duties and Freedoms’, I sensed, perhaps wrongly, the subtending presence in the very terms of the debate of that common, but I believe erroneous, assumption that the artist’s individual freedoms and social responsibilities stand in some sort of irreconcilable and potentially paralysing opposition which is somehow destined to reproduce itself in one historical situation after another.

In fact, there are many historical situations in .which this opposition cannot take us very far. For example, an artist who works under the ‘Socialist Realist’ system in, say, the USSR can fulfill his social responsibilities only by an apparently individualist defiance of his ‘social duty’, at least as that is externally defined by the official artists’ organizations, the Party, and the State. Not every artist who defies the ‘Socialist Realist’ system is necessarily exercising social responsibility; but for those who attempt through their art to bear witness to the truth as they see it, individualistic defiance constitutes social responsibility. Take Ernst Neizvestny : in all of the USSR there was probably no artist with a comparable individualistic, narcissistic energy. But Neizvestny rejected his so-called ‘social duties’ and harnessed his narcissism for the creation of new and monumental sculptural forms which function not only as a great visual shout for the exploited, the suffering and the oppressed everywhere, but also imply within the way that they have been made that there is hope for a changed and a better future.2

Ernst Neizvestny

The situation for Fine Artists in Britain is very different, but here too the simple opposition of individual freedoms and social responsibilities does not work. The post-war Welfare State has invested the artist with no official ‘social duty’ which he can choose to transform into genuine social responsibility; in return for state patronage and support our artists are not required to depict cars coming off the production line at British Leyland, Party Conferences, or ‘glorious’ moments from Britain’s imperial past. Indeed, they are not required to do anything at all. The Fine Art tradition has thus become marginalized and peripheralized, and Fine Artists find they have been granted every freedom except the only one without which the others count as nothing : the freedom to act socially. It is only a mild exaggeration to say that now no one wants Fine Artists, except Fine Artists, and that neither they nor anyone else have the slightest idea what they should be doing, or for whom they should be doing it. Thus, far from there being an awkward tension between ‘social duty’ on the one hand and individual freedom on the other, it is possible to say that a major infringement of the freedom of the artist at the moment is his lack of a genuine social function. This, as I see it, is the paradox of the position of the Fine Artist after modernism. But how has this situation arisen?

Raymond Williams has pointed out how in the closing decades of the eighteenth and the opening decades of the nineteenth centuries the word ‘art’ changed its meaning.3 When written with a capital ‘A’ it came to stand not for just any human skill (as previously) but only for certain ‘imaginative’ or ‘creative’ skills; moreover, ‘Art’ (with a capital ‘A’) came also to signify a special kind of truth, ‘imaginative truth’, and artist, a special kind of person, that is a genius or purveyor of this truth. Subtending this etymological change was the emergence of a historically new phenomenon for Britain, a professional Fine Art tradition.

Given the state of national economic and political development, the arrival of this tradition was exceptionally tardy: the causes of this belatedness (which inflected the course of the subsequent development of British art) are to be sought in that peculiar lacuna in the national visual tradition which extends from the beginning of the 16th century until the emergence of Hogarth in the 18th. The medieval crafts had been eroded by baronial wars and technological advance and had fallen into terminal decay in the later 15th century; they were effectively extinguished by the mid 1530s. Although, as Engels remarked, a new class of ‘upstart landlords . . . with habits and tendencies far more bourgeois than feudal’ was coming into being at this time, a prevalent iconoclastic puritanism, associated with the dissolution of the monasteries and the formation of a national church, was among those factors which inhibited the development of a secular painting peculiar to this new class. At the level of the visual, Britain thus lacked a ‘Renaissance’: no ‘humanistic’ world-view emerged within a flourishing tradition of ecclesiastical representation, to transcend and supersede it, as happened, for example, in the Italian city states. In Britain the prior medieval tradition was literally erased during the Reformation.

Subsequently, the courts required only portraiture: competent practitioners above the artisanal level tended to be imported. Henry VII patronized a Flemish artist, Mabuse;

Henry VIII, Holbein. Successive monarchs employed immigrant painters: Scrots, Eworth, Gheeraerts, Van Somer, Mytens, Van Dyck and Lely. These artists brought with them a heterogeneous assortment of European modes. Although some took on individual pupils and apprentices, in no sense did this amount to a national visual tradition. The principal exception accentuates the predicament: Nicholas Hilliard arguably emerged out of the subtending artisanal tradition to produce a peculiarly English world-view of Queen Elizabeth and her courtiers. But Hilliard’s pictorial conception was that of a miniaturist who looked back towards the representational modes of medieval manuscript illumination. The retardate character of English painting can be gauged when one recalls that Hilliard — the most illustrious figure not only of Elizabethan painting but among all indigenous artists during the long visual lacuna — was born some seventy years after Titian. (Historical materialism has as yet no way of assessing how far this peculiar stunting of visual expression can be correlated with the precocious efflorescence of literature in the same period.)

The agrarian capitalists who consolidated their power in the 17th century created a demand for two limited but indigenous genres of painting, country-house conversation pieces, and sporting paintings — particularly of horses; but visual practice was suspended in a vacuum between aristocratic patronage and an open market. ‘Art’ and artists had yet to come into being. Horace Walpole believed this was ‘the period in which the arts were sunk to their lowest ebb in Britain’. Change came with Hogarth: he was conscious of the need to found a national visual tradition, and to oppose debased European imports. By making use of mass sale engravings, he forged a new economic (and aesthetic) base for image-making which opened a potential space (allowing for satire) between himself and the ruling class. This enabled him to refer to areas of experience — poverty, oppression, sexuality, work, criminality, cruelty and politicking — previously excluded from painting. Uniquely, he depicted the whole social range from the Royal family to the derelicts of gin lane. His real subject — rare enough in any branch of British cultural activity — was English society in its totality. But his project was only briefly possible. Although largely freed from agrarian class patronage, he opposed himself to the professionalization of painting, especially to the establishment of a national academy. He thus came into being between two traditions and was able to achieve something in terms of scope and audience which had never been before in English painting, and would never be again.

During the later eighteenth century, the outlines of the professional Fine Art tradition became increasingly discernible. It was characterized by the establishment of an open market in pictures. (This had the effect of turning the artist effectively into a primitive capitalist rather than a skilled craftsman.) The old system based upon apprenticeship and direct patronage broke up and was eventually almost entirely displaced. All sorts of related developments accompanied this change: art schools began to appear; professional organizations and institutions including a Royal Academy, were established; exhibitions open to the public, salons, journals dealing with modern art, professors of painting, and very soon museums too began to appear for the first time. None of these had existed previously. When we talk about the problems, duties, and freedoms of artists, even today, we are not talking about a transhistorical category, but about the achievements, difficulties, and potentialities — if any — of those who are working within a professional apparatus which came into being in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and which now appears to be threatened.

John Constable

The emergence of the professional Fine Art tradition was associated with, indeed was a direct product of, the transformation of the economic structure in Britain by the emergence of industrial capitalism. It would be simple if we could say that professional Fine Artists emerged and expressed the point of view of the industrial bourgeoisie; but you have only to look at the pictures themselves to realize that this cannot be the whole story. In his discourses Reynolds may have yearned for a new ‘history’ painting which we might interpret as the metaphorical vision of a class conscious that it was forging its own history; but what he produced in practice consisted largely of portraits of My Lords and Ladies embellished with flourishes of the aristocratic, European Grand Manner. Similarly, in the early nineteenth century John Constable expressed the desire to develop landscape painting as a branch of ‘Natural Philosophy’. He made impressive advances in the precise representation of the empirical world in the richness of its momentary changes and the processes of its natural becoming. But even he seems to have been held back and inhibited in his work; the economic necessity of continuing to produce ‘country house portraits’ also seems to have involved him in the internal retention of the point of view of the rural landlord. Despite the sketches there is a peculiar identity between his known political views and the nostalgic, noonday stasis of many of his larger pictures, especially perhaps The Cornfield. Similarly, the main difference between the Royal Academy and the European salons lay precisely in the fact that it was a Royal Academy, whose finances were guaranteed by the monarch himself. Thus, although it is true to say that the new Fine Art tradition was a product of the industrial revolution, we cannot simply identify the practice of its painters with the vision of an emergent, industrial middle class.

The causes of this peculiar disjuncture lie deep in the history of the social formation in Britain: here I can do no more than indicate them schematically. Perry Anderson and Tom Nairn have pointed to the way in which capitalism was established throughout the countryside in Britain by the destruction of the peasantry, the imposition of enclosures and the development of intensive farming long before the industrial revolution.4 They have suggested that no major conflict arose between the prior agrarian class and the rising industrial bourgeoisie because these classes shared a mode of production in common: capitalism. Thus there was no real social, political, or cultural revolution associated with the coming into being of an industrial bourgeoisie. Although the latter effected the titanic achievement of an industrial revolution, socially, politically, and culturally — after surmounting the tensions which came to a head in the 1830s — they fused with the old formerly aristocratic, agrarian elements to form a new hegemonic ruling bloc with a highly idiosyncratic ideology. Thus that selfsame bourgeoisie which unleashed the transforming process of the industrial revolution, conserved the Crown, Black Rod, a House of Lords, innumerable other ‘ornamental drones’ and goodness knows what other clutter from feudal and aristocratic times: it developed no new world view peculiar to itself. Now it was precisely for the benefit of, and hence through the spectacles of, this highly eccentric ruling bloc that professional Fine Artists were required to represent the world. I believe that this why so much Victorian painting seems to us to combine heterogeneous elements, to possess, albeit unwittingly, an almost surrealist quality. I also believe that the famous flat or linear aspect of British art in part arises because the flattened forms characteristic of feudalism (e.g. in stained glass windows, altar pieces, and manuscript illumination) were never thoroughly challenged and overthrown by an indigenous bourgeois realism which emphasized the tangibility and three- dimensional materiality of things. The rise of the bourgeoisie in Britain culminated in Burne-Jones’s angels, and the flat ethereality of Pre-Raphaelitism, not in the concrete sensuousness of Courbet’s apples, rocks and flesh.

Burne-Jones

It is characteristic of ruling classes — even bourgeois ruling classes shot through with feudal and aristocratic residues and encumbrances — that they like to represent everything which is peculiar to themselves, their own historically specific values, as if they were universal and eternal. John Berger has demonstrated how the representational conventions of the professional Fine Art tradition, conventions of pose, chiaroscuro, perspective, anatomy, etc., came to be taught not as the conventions which they were, but as the way of depicting ‘The Truth’.5 The same was also true of the emergent ideology of art itself. Many artists, and the new practitioners of art history too, began to propagate the view that there was a continuum of ‘Art’ (with a capital ‘A’) extending back in an unbroken chain to the Stone Age. Thus they identified the images produced by the Fine Art professionals of nineteenth-century capitalism as the apotheosis or consummation of an evolutionary tradition of ‘Art’ almost magically constituted in theory without reference to lived history, with its ruptures and divisions.

This sort of thinking, exemplified in the lay-out of museums and public art galleries, helped to create what can best be called the historicist funnel of ‘Art History’. Art historians accepted as legitimate objects of study, even if they sometimes labelled them as primitive, a very wide range of images from, say, a decorated Greek mirror to a Roman mosaic, or a Christian altar-piece. Such things had served disparate functions within disparate past cultures. All that they had in common was that they were images made by men and women. On the other hand, from existing bourgeois societies art historians accepted only the particular products of the professional Fine Art traditions. Everything else was excluded.

This kind of distortion of history should not blind us to the fact that, say, in most feudal societies there was nothing which even approximated to ‘Art’ (with a capital ‘A’) and certainly no tradition of professional, trained Fine Artists who produced free-standing works for an open-market, nor any ideology which associated the creation of visual images with ‘specialness’, or the expression of individual, ‘imaginative truth’. Thus it was not ‘Art’ (with a capital ‘A’) that formed an unbroken continuum stretching back into the earliest social formations but rather the production of images of one sort or another which took very different forms in different cultures; in Western, medieval, feudal societies such images were often realized through manuscript illumination, stained-glass windows, tapestries, wall paintings, and so on: never through free-standing oil paintings on canvas.

By and large, the professional Fine Art Tradition in Britain served the composite ruling class very well; artists went to art schools where they acquired the skilful use of certain pictorial conventions which they then put to work in representing the world to the ruling class from its point of view. These conventions were capable of fully expressing only the area of experience peculiar to that class. Some artists tried to extend them, to put them to uses — such as the depiction of working- class experience — for which they were not intended; such attempts in Britain, however, tended to be mechanical. Because the British lacked a progressive bourgeois vision they could produce a Ford Madox Brown but not a Daumier or a Millet. The peculiar ataraxy of the bourgeois aesthetic in nineteenth century England goes far beyond subject matter; after Constable the attempt to depict change to find visual equivalents for ‘moments of becoming’ in the natural and social worlds simply freezes. The Victorian world view, as expressed through Victorian paintings, is one of stasis. Even in the later nineteenth century no indigenous minority tendencies like the Impressionism of France, Cezanne’s dialectical vision, or the later manifestation of Cubism arose; all these aesthetics were characterized by a preoccupation with the depiction of change and becoming. Compare, say, a Rossetti painting with an Alma Tadema. These artists occupied polar opposites within the British Fine Art tradition and yet today we are more likely to be impressed by their similarities than by their minor differences, so narrow was the range of painting in this country in the last century. In the absence of a progressive bourgeois culture, artists fulfilled the ‘social duty’ demanded of them by the ruling class almost with servility and, despite the ideology of artistical ‘specialness’, without even that degree of imaginative distancing which led, on the continent, to the creation of Bohemia.6

Although the work of the professional Fine Artists thus dominated the visual tradition, as they re-constituted the world in images for the bourgeoisie, throughout the nineteenth century we can trace the gradual emergence of modes of reproducing and representing the world based on conventions distinct from those of the Fine Art tradition. Between 1795 and the turn of the century lithography, or chemical printing from stone, had been invented; within thirty years a colour process was in commercial use. By 1826 photography too had come into being.

Now it is sometimes suggested that it was simply the invention of these new techniques which led to the displacement of the Fine Art tradition. I cannot accept this. Professional Fine Artists, with their aesthetic conventions and their ideology of ‘Art’, remained the unquestioned, culturally central, hegemonizing component within the visual tradition until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The professional Fine Art tradition was not displaced until the competitive, entrepreneurial capitalism (whose interests it had come into being to serve) was itself superseded in the late nineteenth century and the earliest years of the twentieth century, by the emergence of the monopoly capitalist system. Among the myriad of global changes associated with this monumental upheaval of the base was the emergence of a new kind of visual tradition, peculiar to the new social and economic order. This constituted a far more profound transformation of the way that images were produced and displayed even than that which had been brought about by the rise of the professional Fine Art practitioners in the eighteenth century. The complexity, diversity, and sheer ubiquity of the visual tradition under monopoly capitalism, involving new mechanical, electrical, cinematic, and most recently holographic means of reproducing all manner of static visual images, entitles us to refer to it as the first ‘Mega- Visual’ tradition in history — a tradition which of course soon included moving as well as static images.

Now the question which really confronts us when we talk about the duties and freedoms of Fine Artists today is what has happened to the old professional Fine Art tradition in this radically changed situation. I have previously used the example of Henry Tate, of Tate Gallery fame, to illustrate this change. The example is a good one and so I hope those of you who have heard or read of it before will forgive me for citing it again.

Henry Tate was born in 1819 and apprenticed to a grocer at the age of thirteen; by the time he was twenty our budding capitalist had his own grocery business; aged thirty he had a chain of shops; aged forty he became partner in a firm of sugar refiners and soon sold off the shops to buy out his partner. In the early 1870s, at the depth of the slump, he patented the revolutionary Boivin and Loiseau sugar refining process rejected by his larger competitors. He then scrapped his original capital investment in the old method, gambled all on the new plant, and won. Soon after he patented the sugar cube. His profits rocketed. As befitted a self-made, entrepreneurial millionaire he frequented the annual exhibitions at the Royal Academy where he bought great numbers of paintings by Hook, Millais, Orchardson, Riviere, Waterhouse and so on to decorate his Streatham home. He gave these to the nation as the kernel of the Tate Gallery, which opened in 1897; and two years later he died.7

Tate had made his very considerable fortune in bitter-sweet competition with other sugar refining families, the Macfies, Fairries, Walkers and Lyles, but within a matter of years of his death all these rival firms had been swallowed up into a new swollen amalgam: Tate and Lyle’s. The growth of such monopolies meant that the kind of individualist, capitalist trajectory which Tate had so successfully pursued in the nineteenth century was much rarer in the twentieth, and with the endangerment of that species of bourgeoisie began the withering, atrophy, and shunting out towards the margins of cultural life of the academic, professional Fine Art tradition which had so efficiently represented the world to the nineteenth century middle classes.

Of course, this is not to say that the new monopolists and their burgeoning corporate empires did not require artists to produce static visual images for them as every ruling class in every known culture had done in the past. On the contrary they had an insatiable, unprecedented greed for images. At first some of the most famous Fine Art professionals benefitted from this. For example, in 1886 Levers, the soap firm, spent a grand total of £50 on advertising; but the previous year their leading rivals, Pears, had taken on Thomas Barratt as a partner. Barratt passionately believed in the value of the new-fangled advertising methods and in 1886 he spent £2,200 in purchasing Millais’ Bubbles to promote his company’s product. To go back to Lever’s accounts we now see that in response, over the next twenty years, they spent a total of £2m, or £100,000 a year, on advertising.

This increase reflected a general trend in Britain and America. In their important study, Monopoly Capitalism, Baran and Sweezy report that, in America, in 1867 expenditure on advertising was about $55m; by 1890 this had reached $360m; and by 1929 it had shot up to $3,426m. The authors point out, ‘from being a relatively unimportant feature of the system [the sales effort] has advanced to the status of one of its decisive nerve centres. In its impact on the economy it is out-ranked only by militarism. In all other aspects of social existence its all pervasive influence is second to none.’8 This may be to exaggerate the relative importance of the sales effort; nonetheless there should be no need to emphasize its significance, or the important role which visual images play within it.

As early as 1889, M.H. Spielmann, writing in The Magazine of Art, was able to predict, ‘we may find that commerce of today will, pecuniarily speaking, fill . . . the empty seat of patronage which was once occupied by the Church’.9 Certainly, the development of monopoly capitalism led to the efflorescence of a new public art, but what Spielmann failed to foresee was that the old Fine Art professionals would get less and less of the new cake. The demands of the monopolists soon created an entirely new profession which established, much as the prior Fine Art profession had done in the late eighteenth century, its own professional organizations, institutes, training courses, journals, codes of practice, and ideology, which notably excluded both concepts of artistic ‘specialness’ and imaginative truth. Ir fact, it might be said that just as monkish manuscript illumination constituted the dominant form of the visual tradition in certain feudal societies, free-standing oil painting produced by Fine Art professionals constituted the dominant form in certain entrepreneurial capitalist societies; but under monopoly capitalism, wherever it established itself, the dominant form of the static visual tradition was advertising.

This is of very great importance. For example, there is a tendency among the more cavalier type of Marxist critics to endeavour by a deft sleight of hand to equate the crisis in the arts, i.e. the indubitable decadence of the professional Fine Art tradition, with the alleged crisis of monopoly capitalism itself. But if we attend to the visual tradition as a whole, and not just to the Fine Art tradition, however much it goes against the grain we are compelled to concede that far from being in a moribund condition monopoly capitalism must be diagnosed as being unnervingly alive. I have already mentioned holograms: it is no accident that their development and display has been sponsored by Guinness. Within a few years, perhaps sooner, we will have to endure the sight of forty foot bottles projected into the night sky over the Thames, and no doubt 100 foot three-dimensional images of British Leyland trucks will be roaming above the hills and valleys of Wales.10 You may not like this prospect: I personally view it with dismay. It does not however indicate the tottering visual bankruptcy of the existing order.

Perhaps more common is the argument that in some sense or other advertising does not really count; nowadays the old continuum theory is sometimes dressed up in smart, leftist fancy dress, significantly usually by those whose leftism is first and foremost an academic, art-historical method. We tend to hear a lot about the enduring ‘autonomy’ of art, and so on. But this position can be defended only through the kind of sophistry which accepts, say, the markings on a Boetian vase, or Lascaux cave paintings, decorated Greek mirrors, Cycladic dolls, Russian icons, or Italian altar-pieces as art, but which denies that billboards, colour supplements, or posters belong to this category while going on to assert that certain (but not all) piles of bricks and certain (but not all) grey monochromes do. I believe that it really only makes sense to talk about the visual tradition as a whole as constituting a relatively enduring and autonomous cultural component. There will always be images but under different social formations they will emerge in different forms and be put to different uses. There is nothing about the institutions or ideology of the professional Fine Art tradition which makes it more likely to endure and to continue to occupy the centre of the visual tradition than, say, the great medieval tradition of manuscript illumination.

Indeed if we look at the Fine Art tradition from the closing decades of the nineteenth century until the present day it is clear that not only has it become progressively less central culturally and socially but internally it has itself been ebbing away. In the late nineteenth century in Britain theologians developed a concept which can usefully be adapted to the Fine Art situation. They found themselves pondering a persistent problem in Christian dogma: Jesus was manifestly often wrong in his judgements and limited in his knowledge yet how could this be if he was really very god of very god, who was, of course, supposed to be omnipotent and omniscient. Charles Gore, a theologian of the Lux Mundi school, attempted to resolve this tricky problem by reviving the idea of kenosis, or divine self-emptying. He held that the knowledge possessed by ‘The Christ’ during his incarnate life was limited because in taking to himself human nature god had actually emptied himself of omniscience and omnipotence. Now it is just such a process of kenosis or selfemptying that characterizes the Fine Art tradition from the late 1880s onwards. Paintings and sculpture acquire an ever more drained out, vacuous character, as if artists were voluntarily relinquishing the skills and techniques which they had previously possessed. But those skills have not vanished altogether. They have been picked up by advertising artists.

W.P. Frith was one of several Victorian artists who complained that the new advertisers were pillaging and pirating his paintings for their own purposes: his picture, The New Frock, had been incorporated without his permission into an ad for Sunlight Soap. If we look at an image like his better known Derby Day we can see how easy it was for this displacement to occur. According to Frith himself, Derby Day was the culmination of fifteen months’ incessant labour. He employed a team to produce it, including 100 models, a photographer who took pictures on the race-course for him, and J. Herring, a specialist, who added the horses. Frith knew exactly whom he was aiming his picture at; when it was first shown at the Academy the crowds were so great that they had to put a special rail round it. Frith then issued a popular print which sold in tens of thousands. It is inconceivable that any professional Fine Artist today would invest so much time, labour, and skill in a single picture. Even if he did so, it is even less conceivable that a crowd of thousands would throng round at its first exhibition. However, the elaborate work on location, the use of numerous models, the hiring of specialist skills, and indeed the eventual mass audience itself are all typical of the way in which the modern advertising poster artist constitutes his images. Indeed, Frith’s image was so close to the conventions of the new tradition that quite recently it was simply taken by the Sunday Times’s advertising agency and blown up with a superimposed slogan to fill their bill-board slots.

Whatever judgement we may wish to reach on Frith’s project, we cannot deny that he was deploying definite skills which enabled him to relate effectively to an audience capable of responding without difficulty to what he was doing. The same is also true of the modern advertising artist. Like Frith’s, his skills too are identifiable and teachable. This is by no means so manifestly true of what the professional Fine Artist does today. A recent sociologist’s study reported that ‘half the tutors and approaching two-thirds of the students of certain art colleges agreed with the proposition that art cannot be taught.’ Understandably the authors then asked, ‘In what sense then are the tutors tutors, the students students, and the colleges colleges? What if any definitionally valid educational processes take place on Pre-Diploma courses?’ The authors reported that nearly all tutors ‘rejected former academic criteria and modalities in art’ — but none had any other conventions to put in their place.11 The kenosis within the professional Fine Art community has reached such an advanced stage that although the apparatus of a profession persists, no professionalism, or no aesthetic, survives to be taught; such a professionalism would be dependent on the social function which the Fine Artist does not have.

Why then has the professional Fine Art tradition not withered away altogether? Why has advertising not supplanted Fine Art in a more definitive sense? Even if we cannot attribute absolute transhistorical resilience to ‘Art’ (with a capital ‘A’), we can say that the Fine Art tradition has acquired a relative autonomy, through its institutional practitioners and intellectuals, which allows it to reproduce itself like the Livery Companies of the City of London, or the Christian Church, long after its social function has been minimalized and marginalized. Its survival has also been assisted by the disdain of the intelligentsia for the new profession of advertising. John Galbraith has pointed out that to ensure attention advertising material purveyed by billboards and television ‘must be raucous and dissonant’. Fie writes: ‘it is also of the utmost importance that’

advertisements ‘convey an impression, however meretricious, of the importance of the goods being sold. The market for soap,’ he continues, ‘can only be managed if the attention of consumers is captured for what, otherwise, is a rather incidental artifact. Accordingly, the smell of soap, the texture of its suds, the whiteness of textiles treated thereby and the resulting esteem and prestige in the neighbourhood are held to be of the highest moment. Housewives are imagined to discuss such matters with an intensity otherwise reserved for unwanted pregnancy and nuclear war. Similarly with cigarettes, laxatives, pain-killers, beer, automobiles, dentifrices, packaged foods and all other significant consumer products.’ But, Galbraith goes on, ‘The educational and scientific estate and the larger intellectual community tend to view this effort with disdain... Thus the paradox. The economy for its success requires organized public bamboozlement. At the same time it nurtures a growing class which feels itself superior to such bamboozlement and deplores it as intellectually corrupt.’12

Although the intellectuals knew that they deplored advertising and indeed all the mass arts, they were much less certain about what images they wanted the residual professional Fine Artists to produce, though they knew that they wished them to continue to be ‘real’ artists who took as their content and subject matter not soap-suds but all that was left after the kenosis, i.e. art itself. This is spelled out in the critical writings of the American modernist-formalist critics. Clement Greenberg, for example, has written: ‘Let painting confine itself to the disposition pure and simple of colour and line and not intrigue us by associations with things we can experience more authentically elsewhere.’13 Geldzahler, a sub-Greenbergian hatchet man of late modernism, has explained that art today ‘is an artists’ art; a critical examination of painting by painters, not necessarily for painters, but for experienced viewers.’ This ‘artists’ art’ was, he said, limited to ‘simple shapes and their relationships’. He thoroughly approved of the fact that ‘there is no anecdote, no allusion, except to other art, nothing outside art itself that might make the viewer more comfortable or give him something to talk about.’ Very soon, of course, even the intellectuals preferred the texture of soap-suds, or whatever, and so there were very few viewers either. This did not worry Geldzahler unduly: ‘There is something unpleasant in the realization that the true audience for the new art is so small and so specialized,’ he wrote. ‘Whether this situation is ideal or necessary is a matter for speculation. It is and has been the situation for several decades and is not likely soon to change.’14

In Britain, the position of the residual professional Fine Art tradition was worse even than in America. There was almost no basis for the acceptance of modernism among the intellectuals with the exception of those few who were themselves involved in the art community. Furthermore, in contrast to the US, the domestic picture market in modernist work failed to boom. Indeed, after the last war an impartial observer might well have come to the conclusion that the Fine Art tradition was about to contract into a residual organ, rooted in the Royal Academy, but with perhaps a ‘populist’ penumbra, serving the needs of a shrinking squirearchy and the continuing demands of clergy, army, Masters of Oxford and Cambridge Colleges, chairmen of the board, sporting men, etc. for portraits of themselves, their fantasies about the past, and animals, boats, and trains.15 But in 1954 Sir Alfred Munnings, sometime President of the Royal Academy and campaigner against ‘Modern Art’, wrote to The Daily Telegraph describing a day out at the Tate with Sir Robert Boothby when they roared with laughter at new English works which, he wrote, ‘today rival the wildest and drollest of French and other foreign cubists, formalists, and expressionists of the past’. The ‘drolleries’ were to flourish, and culturally, at least, to eclipse the residual academic works.

For just at the moment when the professional Fine Art tradition in Britain seemed destined to go the way of manuscript illumination, politics stepped in to save it. Although, unlike the CIA,16 MI5 did not choose to promote modernism throughout the world as a cultural instrument in the Cold War, the post-war Welfare State became heavily involved in the patronage of it. Keynes advocated increased intervention in the economy to ameliorate the worse effects of capitalism. One of the first institutions of the Welfare State to be set up after the declaration of peace was the Arts Council. So far as visual arts policy was concerned, the Arts Council committed itself to the exhibition and subsidy of the professional Fine Arts tradition alone; it commissioned nothing and imposed no constraints on artists of any kind. According to the Council, professional Fine Artists were supposed to be ‘free’ in an absolute, unconditional sense. The early Arts Council reports make clear that this policy was intended to show the world that in the so-called ‘Free World’ artists produce works of great beauty and imaginative strength, whereas the Soviet ‘Socialist Realist’ system produces only hollow, rhetorical, academic art officiel. Keynes himself wrote of ‘individual and free, undisciplined, unregimented, uncontrolled’ artists ushering in a new Golden Age of the arts which, he said, would recall ‘the great ages of a communal civilized life’.17 Moreover the Arts Council itself was no more than the cherry on the top of the state patronage cake. This included increased subsidies to museums and above all the rapid expansion of the art education system.

The injection of money into the Fine Art tradition on what has come to be called the ‘hands-off’, or totally unconditional basis, has proved an unmitigated failure. Far from producing the new Golden Age, the splendid efflorescence envisaged in the Keynesian dream, it has ushered in an unparalleled decadence. Piles of bricks, folded blankets, soiled nappies, grey monochromes, and what have you, can hardly demonstrate to those nasty Russians, or to anyone else for that matter, the creative power with which ‘freedom’ invests our artists in the West.

What went wrong? The real comparison was never between the residual Fine Art professionals in the West and the ‘Socialist Realists’ in the USSR, but between their respective visual traditions as a whole. Thus advertising artists served the interests of the ruling organizations in the West just as ‘Socialist Realists’ served the Party and the State in the USSR. The majority of artists under monopoly capitalism were thus hardly more ‘free’ than under the Soviet system. As servants of the great commercial corporations they were required to produce visual lies about cigarettes, beer, cars and soap suds, whereas Socialist Realists were required to produce parallel lies about the condition of the peasantry and the proletariat in the Soviet Union. Monopoly Capitalism thus had its art officiel, too, which, if anything, was more pervasive, banalizing, and destructive of genuine imaginative creativity than its equivalent in the USSR.

Meanwhile, it soon became apparent that whatever freedoms subsidized professional Fine Artists in Britain had been given, they had been deprived of the greatest freedom of all: the freedom to act socially. What were they supposed to be doing? For whom were they supposed to do it? They just had to be artists, and neither the Arts Council, nor the Tate, nor anyone else was prepared to tell them what that meant. Some sought to escape merely by imitating what the Mega- Visual professionals were doing: hence Pop Art. But it became more and more apparent that the subsidized Fine Art professionals were becoming like Red Indians herded into a reservation. Their state hand-outs meant that they could not die a decent death, nor were they likely to drift off and take up some other activity in the world beyond the art world corral. And yet, by the very fact that they were artists, they were insulated from lived experience, from social life beyond the art world compound. As people on reservations are wont to do, many committed incest: i.e. they did nothing but produce paintings about paintings, and train painters to produce yet more paintings about paintings, leading to an endless tide of vast, boring, thoroughly abstract pictures, expansive in nothing except their repetitive vacuity. Others of course went insane, and, abandoning their ‘traditional’ crafts altogether, raced round the reservation tearing off their clothes, gathering leaves and twigs, sitting in baths of bull’s blood, getting drunk, walking about with rods on their heads, insisting that their excrement, or sanitary towels, were ‘Art’ — either with or without the capital ‘A’.

Recently it has become quite clear that something has to be done; but there is little agreement about what. False solutions abound: in 1978, a crude ‘Social Functionalism’ was paraded at several exhibitions, most notably the justifiably slated ‘Art for Whom?’ show at the Serpentine. Richard Cork, a recent convert to this tendency, ended a polemical article with the sentence, ‘Art for society’s sake ought to become the new rallying-cry and never be lost sight of again.’18 The kind of work he appeared to favour was either the most deadening, dull, derivative, work carried out in a quasi-‘Socialist Realist’ style or the sort of modernist, non-visual art practice which packages bad sociology and even more dreadful Lacanian structuralism and presents them as art because they would not stand up for one moment when presented in any other way. Now it may be that those who are peddling this solution at the moment are no worse than naive. Time will show. But one would be foolish to forget that it was under just such banners as ‘Art for society’s sake’ that the National Socialists made bonfires of ‘decadent’, that was very often truthful, art. When ‘society’ is posited as an unqualified, homogeneous mass in this way we are forced to admit that we have had altogether too much of ‘Art for society’s sake’. But, in the end, it is probably not necessary to take this ‘Social Functionalist’ charade too seriously. To revert to our earlier metaphor it is rather as if some Red Indians within the reservation rebelled by dressing up in factory workers’ overalls, without, of course, ever leaving the confines of the corral. This sort of protest tends to fade out through its own ineptitude. Unlike the ‘Social Functionalists’ I believe that it is absurd superficially to politicize overt content and subject matter and then to shout, ‘Look, we are acting socially!’ But, despite everything I have said, I believe the professional Fine Art tradition is worth preserving. Why? Simply because it is here and only here that even the potentiality exists for the imaginative, truthful, depiction of experience through visual images, in the richness of its actuality and possible becoming. This is not an idealist assertion: despite all that I have said about the ideological character of the concept of ‘Art’, I consider that certain material practices — namely drawing, painting, and sculpture — preserved within the Fine Art traditions cannot themselves be reduced to ideology — least of all to bourgeois ideology. It is not just that these practices have a long history antedating that of ‘Art’ and artists: the material way in which representations are imaginatively constituted through them cannot be reproduced through even the most sophisticated ‘Mega-Visual’ techniques in static imagery. (The hologram, for example, can only reproduce a mechanically reflected image.) For these reasons despite its roots in emergent bourgeois institutions, despite the historical specificity of its conventions, despite the narrowness and limitations of its past achievement in Britain, and its virtually unmitigated decadence in the present, despite all this, I believe that the professional Fine Art tradition should be defended. For this to happen, the art community must change position rather than posture. From a new position one can act effectively in a different way; a new posture is just for show. Concretely, this means the pursuit of changes in the existing system of state patronage, changes in art education, and changes in the museum system. For example, it could involve the development of machinery for implementing group or community commissioning of artists (with a right of rejection of the end product); the introduction of mural techniques courses into the Pre-Diploma syllabus; and an overhaul of the currently disastrous procedures through which the Tate makes its acquisitions in modern art. The Arts Council itself may have much to learn from those small-scale, local traditions of image-making which, far from the failure at the centre of the modernist compound, have persisted in relation to small, disparate, often localized, but very definite and tangible publics.

Although I regard measures of this kind as necessary, I see them as also being relatively independent of the question of aesthetics. The process of modernist kenosis means that the professional Fine Art practitioner has no aesthetic, by which I mean, in this context, no identifiable skills and no set of usable representational conventions in the present. There are those, including many ‘Social Functionalists’, who simply wish to revive the old 19th century bourgeois aesthetic and mechanically to apply it to contemporary social and working- class subjects. Self-evidently, this is a disastrous course. However, in more general terms, it may be said that what the professional Fine Artist lacks, whether or not he is reinstated with a genuine social function, is that initial resistance at the level of the materiality of his practice which Raymond Williams has described as the necessary constraint before any freedom of expression is possible, for writers; deprived of 19th century pictorial conventions, the Fine Artist appears to have no language. One way out of this impasse may be to begin to emphasise again the specificities and potentialities of those material practices, drawing, painting and sculpture, which are not reducible to the ideology of ‘Art’. Indeed, not all bourgeois achievement within these practices is necessarily so reducible: the classical tradition and science of ‘expression’, for example, owed much to the scrutiny of certain material elements of existence, and biological processes, which, though mediated by specific social and historical conditions, are not utterly transformed by them.

The preservation of the Fine Art tradition, and of these material practices, seems to me a political imperative. If we look to the possible historical future, I am not prepared to put it more strongly than that, to a future of genuine socialism, one can foresee that the genuinely free artist will be in a culturally central position again. In such a society, the truthful, imaginative, creative depiction of experience through visual images would take the place of both the drab ‘Socialist Realism’ we see in the USSR today, and the banal spectacle of corporate advertising. These artists will be free to act socially not in any travestied sense, but in the fullest sense, to act socially, that is, within a socialist society. What will their works be like? We do not know. We cannot even be certain that we know what the experiences they will be endeavouring to represent will be like. Nevertheless, in the present the visual artist must dare to take his standards from this possible future. He must, and I say must simply because in effect he has no choice if he is to produce anything worthwhile, try to produce, a ‘moment of becoming’, or a visual equivalent of that future which realizes a glimpse of it as an image now. The artist who does this, through whatever ‘style’ or composite of styles in which he works, will embody exactly that socially responsible individualism which I set out by hinting at.

It has sometimes been said that when I talk about ‘moments of becoming’ I am talking about a mystical or quasi-religious experience. I cannot accept this view. I am not advocating some vague utopianism. On the contrary, I would argue that we can learn about our future potentialities only by attending more closely to our physical and material being in the present. (If the concept of transcendence means anything to me it is transcendence through history, not above history.) Like the Italian Marxist, Sebastiano Timpanaro, I believe there are elements of biological experience which remain relatively constant despite changes at the historical and socioeconomic levels.19 One such relatively constant component was effectively suppressed, or conspicuously ignored, for social reasons, by the Victorian Fine Art professional aesthetic: significantly, that was the experience of becoming itself. The new aesthetic which we can only hope to realize in momentary fashion, the new realism in effect, must contain an equivalent for that experience.

The physicist A.S. Eddington — who was, admittedly, an idealist ‘in the last instance’ — once contrasted the nature of the experience of colour with that of becoming. Eddington’s point was that the experience of colour is wholly subjective: what he calls ‘mind-spinning’, or mental sensation. Colour bears no resemblance to its underlying physical cause or its ‘scientific equivalent’ of electro-magnetic wave-length. Thus Eddington believed that when a subject experiences colour he does so at many removes from the world which provides the stimuli: ‘we may follow the influences of the physical world up to the door of the mind’, he writes, ‘then ring the doorbell and depart.’ But he goes on to say that the case of the experience of becoming is very different indeed. ‘We must regard’, he wrote, ‘the feeling of “becoming” as (in some respects at least) a true mental insight into the physical condition which determines it. If there is any experience in which this mystery of mental recognition can be interpreted as insight rather than image-building, it should be the experience of “becoming”; because in this case the elaborate nerve mechanism does not intervene.’ Thus Eddington concludes: ‘ “becoming” is a reality — or the nearest we can get to a description of reality. We are convinced that a dynamic character must be attributed to the external world. I do not see how the essence of “becoming” can be much different from what it appears to us to be.’20

I believe that imaginative image-building has to attempt to find a visual equivalent for becoming: indeed, the hope for a new ‘realism’ may depend upon this. Some of those artists who are attempting to use their freedom with social responsibility by taking their standards from the future may at least hope to make some progress by further exploration of this possibility.