It must be said, however, that Bell's concept of Significant Form (borrowed from Roger Fry), and his idea of aesthetic emotion, are rather unfashionable nowadays. More characteristic of current thinking is the view put forward by the aesthetic philosopher, B. R. Tilghmann, in his book But is it Art? Tilghmann is concerned with the inadequacy of traditional aesthetic theories to deal with the sort of phenomena I have been discussing, from Duchamp's urinal to Andre's bricks. Tilghmann argues that the very idea of a theory or definition of art is a confused one. This confusion, he believes, arises from the fact that the language of aesthetic theory has simply lost contact with the sort of everyday practice we engage in when we look appreciatively at urinals, piles of bricks, muddy smears or acts of castration. Instead of trying to stretch the old aesthetic theories to accommodate these new kinds of artistic practice, we should be elaborating new theories appropriate to the new sorts of practice.

These, then, are two opposing approaches to the problem of anaesthetic art objects: the Bell position, which dismisses those objects which do not give rise to aesthetic effect - anaesthetic objects - out of the category of 'Art' altogether; and the Tilghmann position, which includes everything which anyone ever designated 'Art' as art, but recommends a rejection of traditional concepts of what is and what is not aesthetic experience.

While most discussions of this issue tend to take up a position somewhere between these polarities, I'd like to argue that this whole line of reasoning should be refused.

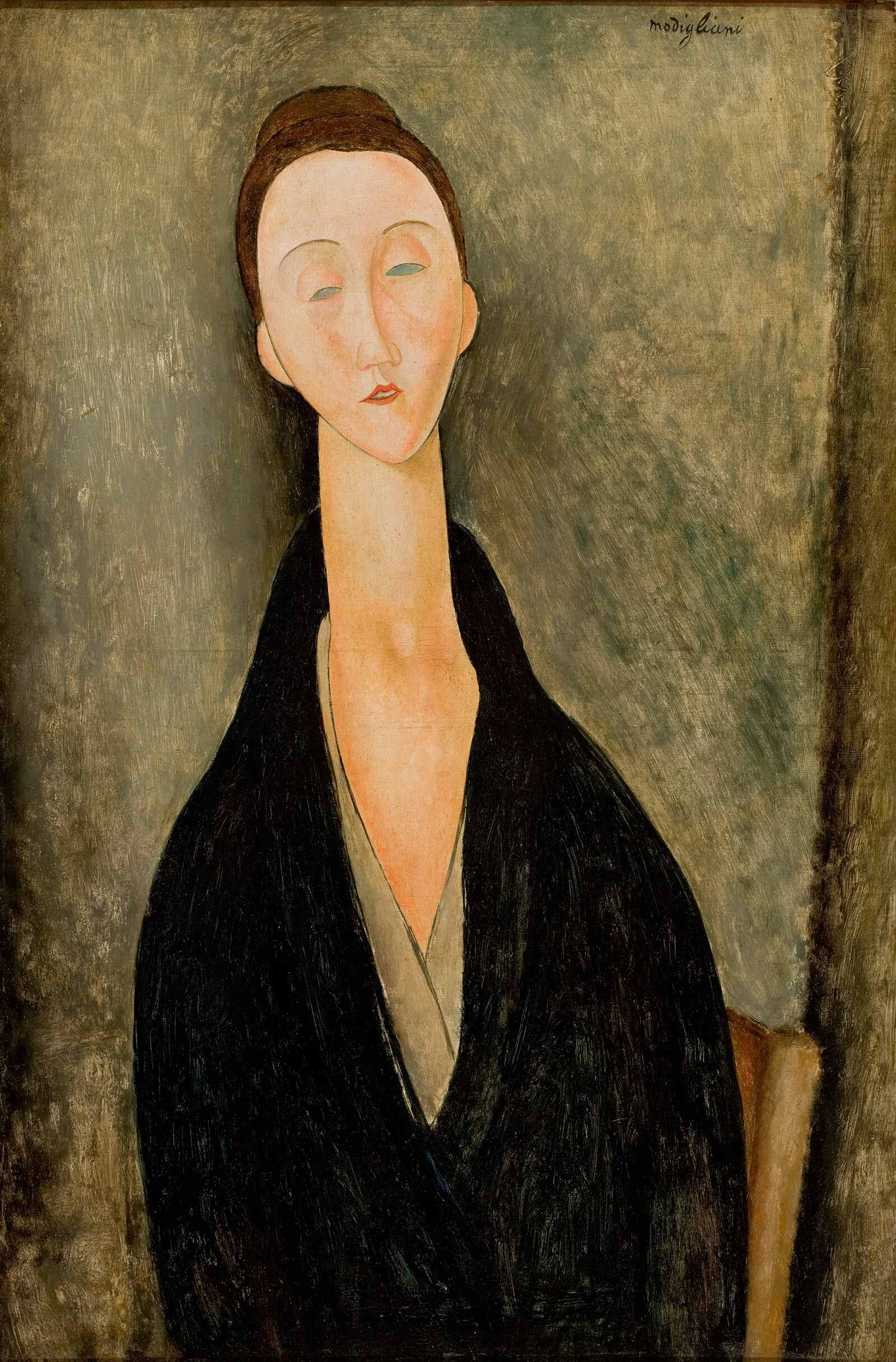

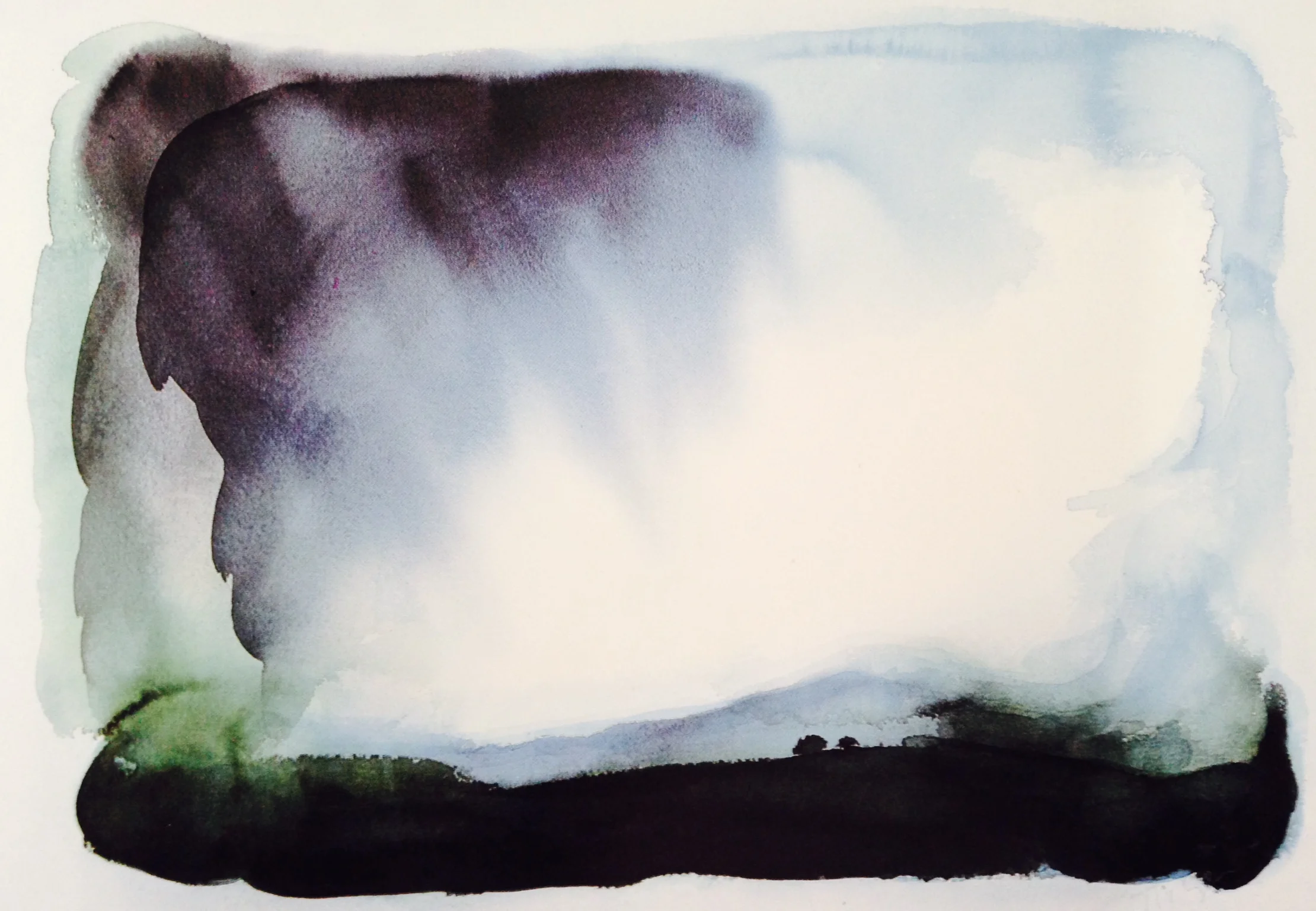

From Baumgarten onwards, aesthetic response and experience were never regarded as being synonymous with what was called 'art'. The early philosophers of the aesthetic recognised that a great many natural phenomena - flowers, minerals, waterfalls, landscapes, forests and the song of the nightingale among them - also gave rise to aesthetic response; a disinterested response, unrelated to price, necessity or whatever. It may well be that this view depended upon a 'Natural Theology'. That is, the belief that the natural world was, in some sense or other, a revelation of the handiwork of God. As Friedrich Schlegel put it, 'As God is to His creation, so is the artist to his own.'

Natural Theology is no longer very popular, even among Christians. And this may have something to do with the fact that most aesthetic theories do not even pay lip service to the 'non-artistic' aspects of the aesthetic experience. My own belief, however, is that the aesthetic faculty has its roots in our continuities with - and ultimately helps establish our differences from - the remainder of the animal kingdom. It can be understood in terms of our specifically human natural history. This aesthetic potentiality, though threatened by the decline of religious belief and the growth of industrial, and latterly, electronic production, is not necessarily destroyed by it.

Rather than see aesthetic theory rewritten in such a way that it incorporates anaesthetic 'Art', I think we should be attending to the independence of 'the Aesthetic Dimension' from 'Art'. If this implies that we should not go along with Tilghmann, I think it also means that we should not go along with Bell's argument. There is, perhaps, something inherently wrongheaded in the view that most works of art are not 'really' works of art at all. (It is reminiscent of that Left argument which accounted for repression in Socialist countries by arguing that most of these countries weren't really Socialist.)

I think one can, indeed should, concede to the Post-Post- Structuralist contextualisers that art is a category constituted within ideology and maintained by institutions, especially the institutions of contemporary art. But the same does not apply to aesthetic experience and aesthetic values, which are orders of innate and inalienably human potentiality. Aesthetic experience of an imaginative order is a terrain which we can enjoy because we are the sort of creatures that we are. Some art embodies aesthetic values and gives rise to aesthetic experience of the highest order, but much art does so only minimally or not at all.

This statement may seem Lea platitude, but important consequences flow from it, since it implies a new - or, more accurately, an old - set of priorities. We must first of all recognise that the freedom to engage and develop innate aesthetic faculties is being impinged upon by present social and cultural policies. Here I am not launching into a defence of 'artistic freedom', a catch-cry which has been used to justify so many contributions to the spread of General Anaesthesia, and which so often proves to be little more than a rallying cry for philistines. On the contrary, I see my practical task as a critic, as one of fostering those circumstances in which the aesthetic potential can thrive, even if it means opposing certain kinds of 'art'.

One question which I have left in brackets is 'Why, in our own time, has there been such a preponderance of anaesthetic art?' For a start, I believe that post-second world war theories of art education must bear much of the blame.

About fifteen years ago, Dr Stuart MacDonald, an historian of art education, referred to what he called 'articidal tendencies' among art teachers. In my language that would be 'aestheticidal tendencies', but that sounds even worse. He was, I think, concerned with counteracting the continuing effects of the 'Basic Design' approach to art education, which was effectively debilitating the idea of Fine Art.

'Art educationalists,' he wrote, 'have been busy demolishing the subject which supports them . . . "Beauty" as a quality of an artefact was vaporised some years back. "Craft", with its connotation of old-fashioned hard work, has been given short shrift. "Artefact" is now being replaced by "museumart". Art education was deleted recently in favour of "visual education".' Dr MacDonald concluded that 'Art itself will go shortly', and he has since been proven right.

This is not to say that art itself has disappeared. Art remains in abundance, but aesthetic education, the nurturing of aesthetic intelligence and, inevitably, the creation of objects of aesthetic value, have all but gone. What is happening in our schools and colleges of art is a calamity of national proportions. Children in some schools receive lessons in 'Design Education' and 'Information Technology' but not in art. An education in art is becoming indistinguishable from an education in design, which is anything but disinterested.

However, it isn't simply education which is to blame for the general anaesthetisation of our culture. One must not forget how left-wing thinkers have long blamed everything on the market in art. This was, in essence, the teaching of my teacher, John Berger, who argued that there was a special relationship between oil painting and capitalism, and that pictures were 'first and foremost' portable capital assets. This led him to express hostility towards the very idea of 'true' aesthetic values, or of connoisseurship, which he saw as being merely derivatives of oil painting's functions in exchange and as property. Despite my respect for Berger I came to feel that there was something strangely circular in the argument that aesthetic discourse and connoisseurship were simply derivatives of the market. If they were, it was not at all clear what it was that the market could be said to be corrupting, distorting or infecting.

Indeed, there was a very real sense in which the left-wing aesthetic theories of the 1960s and 1970s provided the 'programme' for the right-wing governments of the 1980s; for that unholy alliance between philistines of the Left and the Right. For example, John Berger argued that photography had displaced painting as the uniquely modern, democratic art-form of the twentieth century. Margaret Thatcher's Government squeezed the Fine Arts courses and shifted everything towards design. Berger argued that museums were 'reactionary' middle-class institutions that should 'logically' be replaced by children's pinboards. Margaret Thatcher proceeded to pressurise every one of our art institutions in a way which the Director of the National Gallery likened to the destruction of the monasteries during the Reformation.

Berger led the assault on the idea of Fine Art values, which he dismissed as 'bourgeois' and anachronistic. Mrs Thatcher initiated a regime of stunning philistinism and destructiveness, which aimed to sweep away the last vestige in public arts policy of exactly those things to which the Marxists had objected. If the point is not to understand the world but to change it, then in England the palm must be awarded to Mrs Thatcher. She 'deconstructed' aesthetic values much more effectively than a thousand polytechnic Marxists and art school Post- Structuralists.

Nowadays, the philistine complicity of Left and Right is a fact of life for Britain's art institutions. Charles Saatchi, the advertising man (inventor of the slogan 'Labour isn't working', which did so much to bring Mrs Thatcher to power), has amassed a large collection of anaesthetic art, praised by many of the trendiest Left theorists of recent years. Meanwhile, Gilbert and George have become the salon artists of our times. Praised by Left critics for their hatred of unique objects, painting and 'elitist' aesthetic ideas, they are vociferous supporters of Mrs Thatcher.

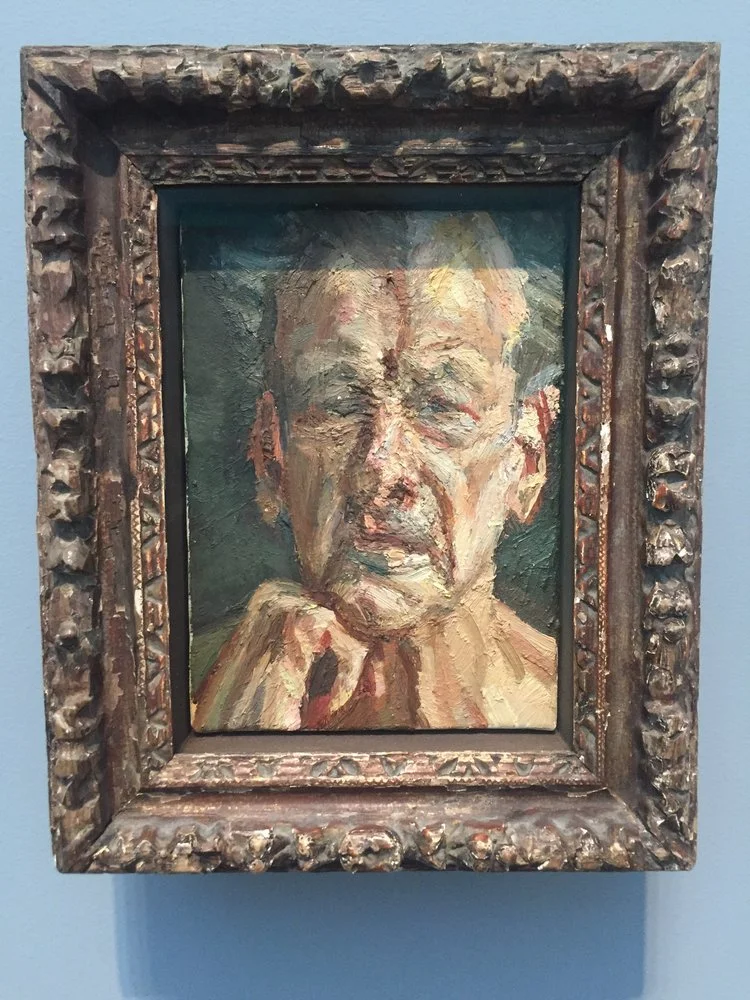

Even though I believe that the left-wing thinkers have provided the best moral justification for the growth of institutional anaesthesia, there is also a ring-wing version of the 'corrupting market' theory, as put forward by Suzi Gablik in her slim and slight book, Has Modernism Failed? Here she suggests that the market somehow corrodes 'Higher Values' through the very nature of commercial activity. However, there remains strong empirical evidence against any such line of reasoning. Gablik does not mention Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, Barbara Hepworth or Ben Nicholson, all of whom were enmeshed in the higher reaches of the art market but whose work embodies precisely those spiritual and aesthetic values which are so often absent from the work of those less commercially- successful artists of today's official, state-subsidised avant- garde. It also seems to me that the evidence of history is against Gablik's view. The market, in and of itself, did not corrupt the art of sixteenth-century Venice or seventeenth-century Holland. On the contrary, in these cases at least, intense activity in the picture markets seems to have been inextricably bound up with extraordinary efflorescences of aesthetic life.

But this observation must also be qualified, since I have no wish to draw any neat equations between the vitality of capitalism and aesthetics. While it is perfectly true that much anaesthetic art involves an element of subsidy, both historically and in our own time public subsidy has also been associated with high aesthetic achievement. One doesn't have to look back to the heyday of Athens or the Gothic period to find instances of such successful uses of public funds. Not so very long ago, the Arts Council and the British Council helped foster an exceptional generation of British artists, including Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland.

While some dealers may prefer to deal in works of quality, rather than in trash, if the art institutions foster a demand for trash, then most dealers will happily service that taste. From this, all one can conclude is that the market clearly does not cause good art (i.e. art of high aesthetic value) or bad art (anaesthetic art, art of low aesthetic value). The operations of the market are, in a certain sense, neutral; neither implying nor eliminating aesthetic values. On its own, the market is simply insufficient or incapable of creating that 'facilitating environment' in which good art can be created. If the Left is wrong to blame the market for destroying art, the Right is equally wrong to suppose that art can be preserved and invigorated by the market.

So what does create a facilitating environment for high aesthetic achievement? Beliefs, faith and even will - but in a very different sense to the way those qualities were manifested in the culture of Modernism or in that of fashionable Post- Modernism.

Modernism resembled the other great styles of the past in at least one important aspect; it aspired to universality, and sought to become 'the genuine and legitimate style of our century' - to use Nikolaus Pevsner's phrase. In this sense, the Modern movement had to be rooted in the Zeitgeist, to be expressive of what Pevsner called 'faith in science and technology, in social science and rational planning, and the romantic faith in speed and the roar of machines'.

Or, as the scientific populariser, C. H. Waddington put it, from a slightly different angle, the artist who wished to paint, or the architect who wished to build for a scientific and sceptical age, 'had to, whether he liked it or not, find out what was left when scepticism had done its worst'.

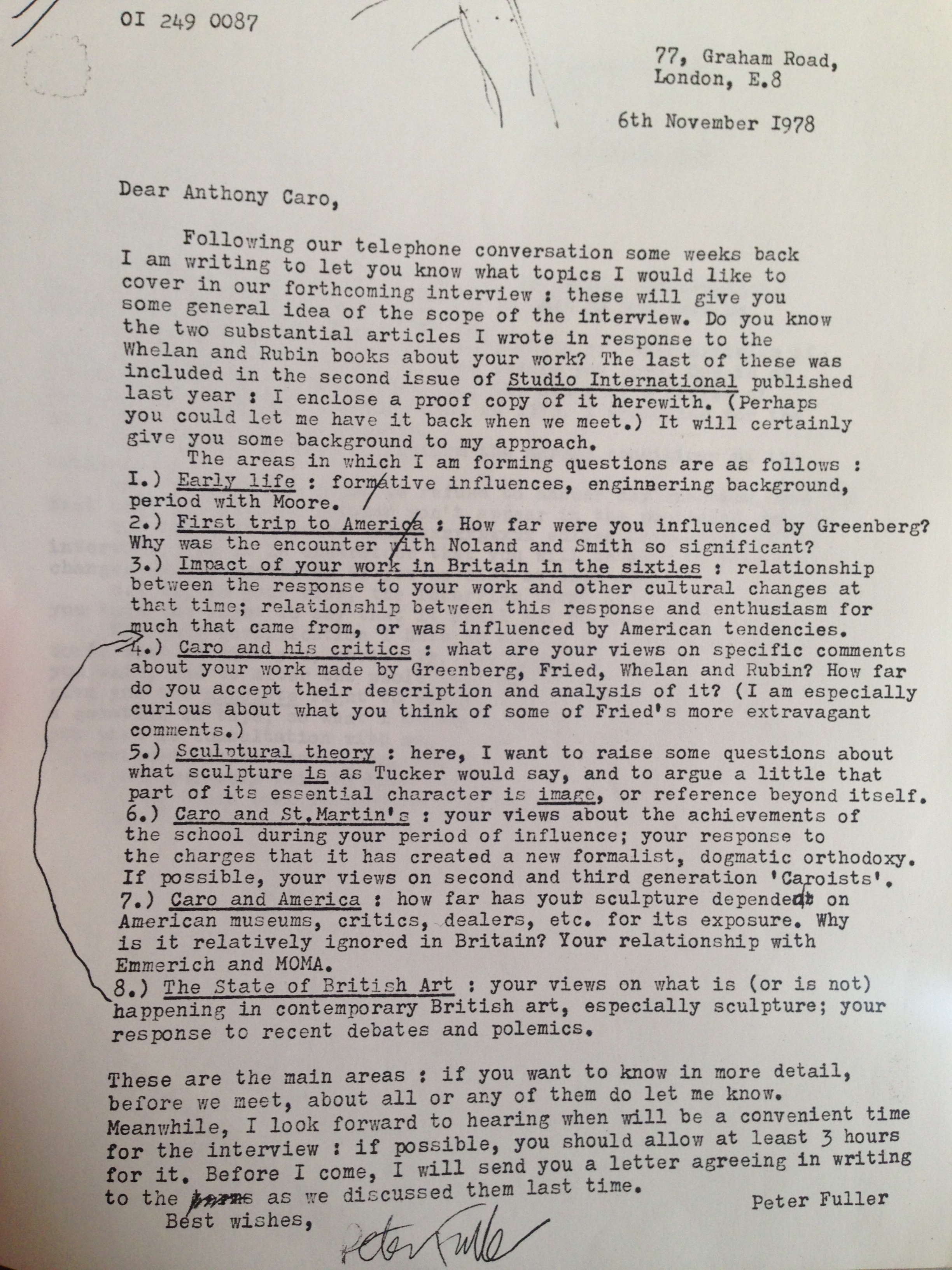

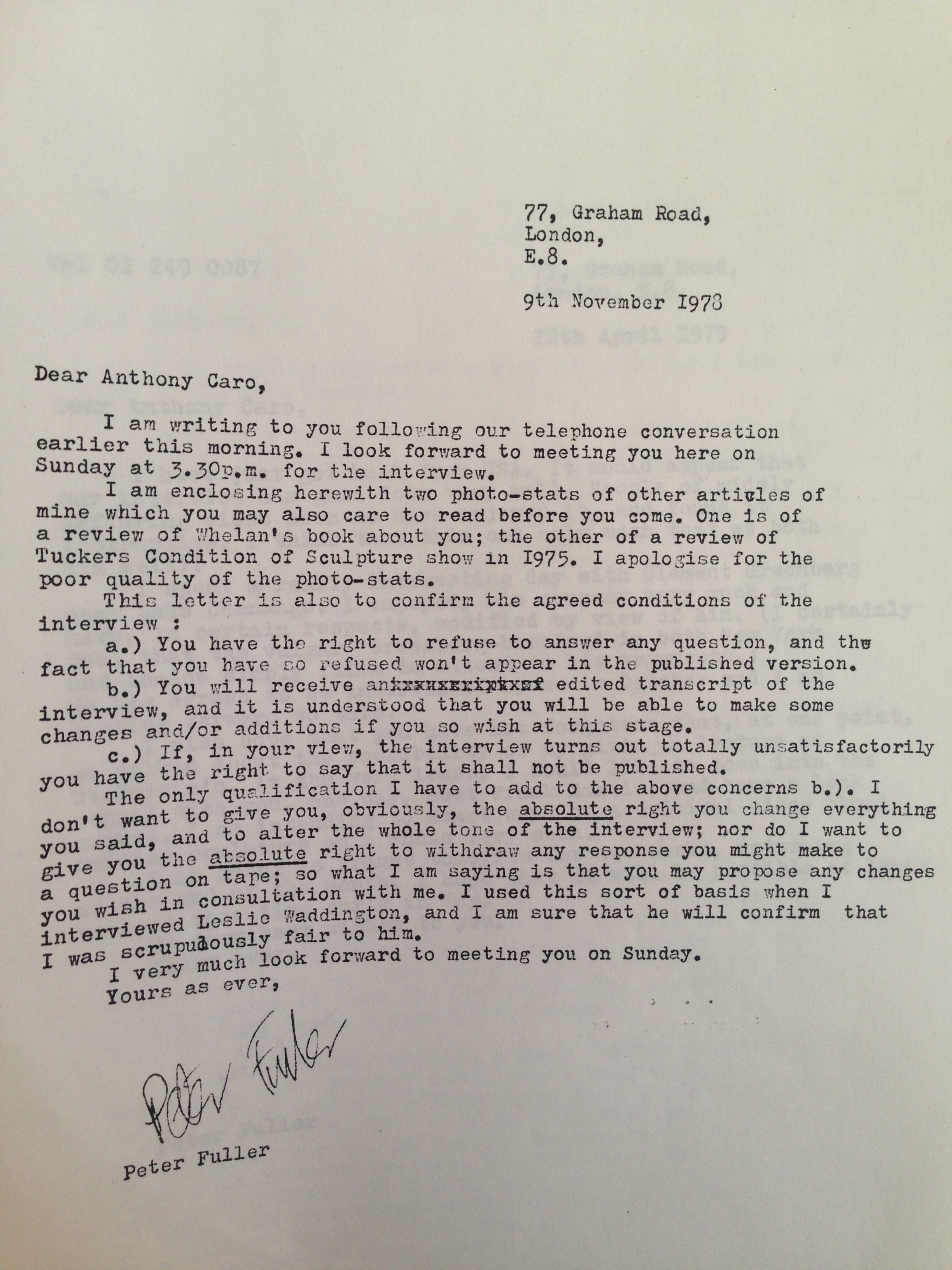

For a critic of American painting like Clement Greenberg in the late 1940s, 'Cubist and Post-Cubist painting and sculpture, ''modern'' furniture [as he called it], decoration and design,' were all part and parcel of the Modern Movement, which he described as 'Our Period Style'.

'The highest aesthetic sensibility,' Greenberg wrote, 'rests on the same basic assumptions as to the nature of reality as does the advanced thinking contemporaneous with it.' For Greenberg, as for Pevsner and Waddington, this 'advanced thinking' was a belligerent, scientific materialism, which, in terms of painting, meant an art of sensation and materials 'uninflated by illegitimate content - no religion or mysticism or political certainties'. Hence Greenberg's hostility to Neo- Romanticism and to the spiritual and humanist aspirations of a sculptor like Henry Moore, whom he accused of being 'half- baked'. (Even Jackson Pollock was reprimanded for his 'Gothickness'.) Hence, too, Greenberg's notorious talk about the ineluctable search for the material essence of the medium, and the pursuit of 'the minimum substance needed to body forth visibility'.

Greenberg's Modernism has had its day, but its passing entailed not merely the waning of a style of architecture or painting, it was bound up with the decline of those beliefs I have outlined above. It became sceptical of its own aspirations to triumph over nature, it began to recognise the limits of that rampant materialism embodied in Pevsner's 'faith in science and technology'. While we may make ever greater use of gadgets such as personal computers and car phones, who among us now believes that such things are initiating us into a brave new world? As for Modernist ideals of social planning, they are quite routinely despised, now that we can see the horrors to which they led. Modernism is, quite simply, no longer open to us as an option.

So what is Post-Modernism? The critic, Charles Jencks set out to answer this question in a pamphlet of that name, and numerous ancillary tomes on Post-Modernism in architecture and art. Jencks's What is Post-Modernism? essentially argues that Post-Modernism is the Counter-Reformation to Modernism. Jencks even contends that it involves 'a new Baroque'. This is disconcerting to those of us still trying to accommodate ourselves to the idea that Post-Modernism in painting simultaneously involves some kind of appeal to classicism, especially to Poussin, the opponent of the Counter-Reformation, par excellence. But matters become even more perplexing when Jencks declares that, unlike the real Counter-Reformation, Post- Modernism involves 'no new religion and faith to give it substance'. Where then is the parallel? A Counter-Reformation without faith? But this is precisely the point. Post-Modernism is the first of the world styles to have no spiritual content at all, not even the misguided faith of materialist Modernism. For what the Post-Modernists are saying is that the certainties of Modernism - its 'meta-narratives' in Jean-Frangois Lyotard's overused phrase - can only be replaced by self-conscious incredulity about everything. Jencks echoes Umberto Eco, who says that Post-Modern man cannot say to his beloved, 'I love you madly', but must express his passion in such terms as, 'As Barbara Cartland would say, "I love you madly'' '; or perhaps 'as Fuller said Jencks said Eco said Barbara Cartland would say "I love you madly".' Likewise, the Post-Modern sculptor cannot build a monument to his nation's dead, he can only build a structure which refers to what such a monument might look like if honouring the dead were what one did, any more, as it were.

Post-Modernism knows no commitments. It is the opposite of that which is engage. Post-Modernism takes up what Jencks himself once described as 'a situational position', in which 'no code is inherently better than any other'. The west front of Wells Cathedral, the Parthenon pediment, the plastic and neon signs of Caesar's Palace, Las Vegas, even the hidden intricacies of a Mies curtain wall: all these things are equally 'interesting'. We are left with a shifting pattern of strategies and substitutes, a shuffling of semiotic codes and devices varying ceaselessly according to audience and circumstances. This is authenticity dissolved. Historicity takes precedence over experience and knowingness is substituted for a genuine sense of tradition.

Speaking as an absolutist and a dogmatist, it has always seemed to me that this Post-Modernist stuff does not escape from the dilemma of all relativist, eclectic and pluralist positions; namely that they are constrained to exempt themselves from those strictures and limitations with which they wish to hem in every other position. For relativism is never able to turn back on itself, to view itself relatively. No relativist will ever proclaim his own position as being only an option, with no greater claims than rival dogmatisms. And so, by subsuming all other positions, relativism is doomed to re-establish itself on the pedestal of the very authoritarianism which it was its sole raison d'etre to challenge. In other words, for all its shifting pluralism, like Modernism before it, Post-Modernist radical eclecticism wants us to know that it is 'the genuine and legitimate style of our century'.

Now I happen to believe, with John Ruskin, that the art and architecture of a nation are great only when they are 'as universal and as established as its language; and when provincial differences of style are nothing more than so many dialects'. I am not a Modernist because I don't believe in a style rooted in the values of triumphant, technist, scientific materialism, and I am not a Post-Modernist because I don't believe in the historical necessity of culture succumbing to a shabby, fairground eclecticism.

Perhaps to prove how all-encompassing Post-Modernism really is, at the end of What is Post-Modernism? Charles Jencks even mentions me. He writes: 'The atheist art critic, Peter Fuller, in his book Images of God: The Consolations of Lost Illusions, calls for the equivalent of a new spirituality based on an ''imaginative yet secular response to nature herself.” ' (This is a bit Post-Modernist - quoting Jencks quoting me.) He continues by arguing that, like himself, Fuller is seeking 'a shared symbolic order of the kind that a religion provides, but without the religion'. He asks, 'How is this to be achieved?'

To answer this question I would like to emphasise three points: the human imagination, the world of natural form and the idea of national traditions in art. In these, I believe, lies the framework for a 'facilitating environment' in which the aesthetic dimension of life can still flourish.

To begin with the imagination, I think it is very important to resist the idea that Post-Modernism is 'the language of freedom'. It would be more appropriate to see it as the language of corporate uniformity in fancy dress. A greater relativist than Jencks was Walter Pater, who, in the mid-nineteenth century, wrote vividly of the fragmentation of human experience into 'impressions' that seemingly did not add up into a coherent whole. Like the Post-Modernists he argued that one ought to take the best from Hellenic and Gothic or Christian traditions, and synthesise them. But, he added, 'what modern art has to do in the service of culture is so to rearrange the details of modern life, as to reflect it, that it may satisfy the spirit'. For Pater, unlike the Post-Modernists, 'a sense of freedom' was rooted not in stylistic eclecticism, but rather in the cultivation of what he called 'imaginative reason'.

To turn specifically to the case of British art, when Baudelaire wrote in the 1850s that British artists were 'representatives of the imagination and the most precious faculties of the human soul', I think that what he was referring to was the persistence in British cultural life of a Romantic tradition, whose twin characteristics were a belief in the human imagination and a close, empirical response to the world of natural form.