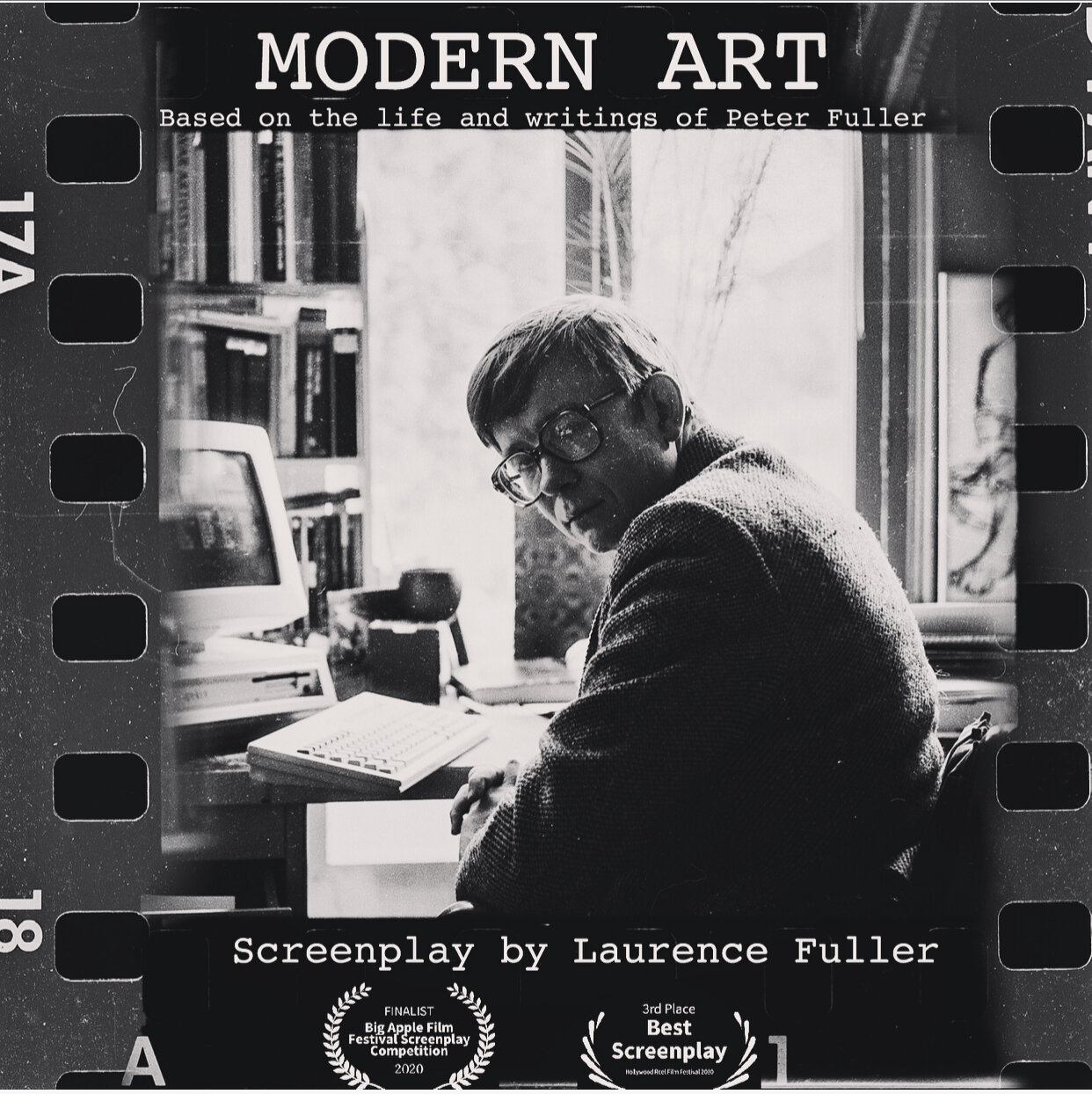

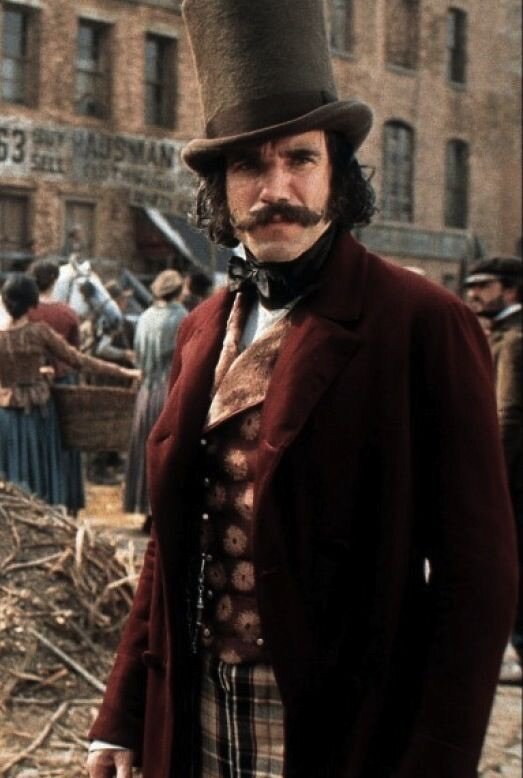

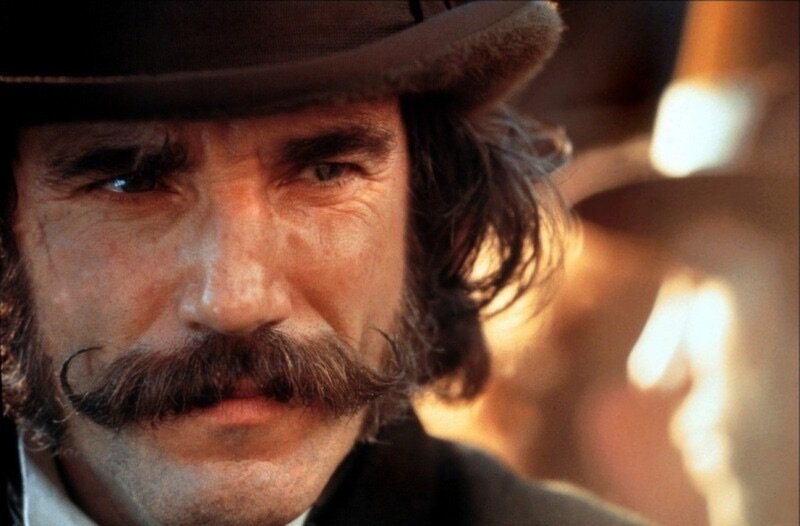

MODERN ART chronicles a life-long rivalry between two mavericks of the London art world instigated by the rebellious art critic Peter Fuller, as he cuts his path from the swinging sixties through the collapse of modern art in Thatcher-era Britain, escalating to a crescendo that reveals the purpose of beauty and the preciousness of life. This Award Winning screenplay was adapted from Peter’s writings by his son.In September 2020 MODERN ART won Best Adapted Screenplay at Burbank International Film Festival - an incredible honor to have Shane Black one of the most successful screenwriters of all time, present me with this award:

As well as Best Screenplay Award at Bristol Independent Film Festival - 1st Place at Page Turner Screenplay Awards: Adaptation and selected to participate in ScreenCraft Drama, Script Summit, and Scriptation Showcase. These new wins add to our list of 25 competition placements so far this year, with the majority being Finalist or higher. See the full list here: MODERN ART

The arts across the world are under attack right now, the telling comments by the likes of Rishi Sunak that artists should ‘re-train’, clearly show the administration’s priorities when it comes to supporting the arts at this time. I know that my father would have had a great deal to say about this. So you can read selected essays by Peter Fuller here on my blog during lockdown! I will be posting regularly.John Berger and Peter’s relationship was fascinating spanned decades and was built on the foundations of true art criticism lived out in an emotional and personal dynamic. Their correspondences remain the most passionate, compelling, engage and moving letters I have ever read. This essay Seeing Berger for obvious reasons signaled a change in their relationship as the son took aim at the father.

SEEING BERGER

by Peter Fuller

In their recent polemic against Ways of Seeing, the authors of Art-Language write, ‘It might be argued that Ways of Seeing has already been dispensed with, that it is obvious to anyone worth talking to that it is a bad book.I can only suppose that I am not worth talking to. Ways of Seeing has had a decisive and continuing effect on my development as a critic. The book and programmes taken together had, I think, a greater influence than any other art critical project of the last decade.

Ways Of Seeing by Mike Dibb starring John Berger

Of course, I am not trying to project Berger beyond criticism. But before I outline my reservations concerning Ways of Seeing, I want to say something about the relationship of my work to Berger’s.2 Berger once wrote of Frederick Antal, the art historian: ‘More than any other man (he) taught me how to write about art.’3 What Berger said of Antal, I can say of him: more than any other man, he taught me how to write about art. It is as simple and as complex as that. I have never been Berger’s pupil in any formal sense nor did I study his work and extract from it any theory, formula, or ‘method’. Rather Berger taught me how to learn to know and to see for myself.

Today, the art world pullulates with self-acclaimed ‘political’ practitioners. It is not easy for us to imagine what things were like in 1951 when Berger began to write his weekly column in the New Statesman. This was the time of the Cold War, of anti-Marxist witch-hunts and hysteria. By bearing witness as a Marxist commentator on art, Berger invited vilification which he received in no uncertain measure. Stephen Spender, for one, unforgivably compared Berger’s first novel, A Painter of Our Time, with Goebbel’s Michael.4 Today, of course, Berger is criticised from his ‘left’ as much as from the right. Art-Language'?, incoherent and illiterate tirade against Berger sneers again and again at his ‘sensitivity’ (as if that were some sort of crime) and accuses him of ‘anti-working class poesy’, ‘immanently empty apologetics for the dominance of bourgeois pseudo-thought’, and so on, and so forth, through 123 barren pages. I respect Berger, however, because he has borne consistent testimony to a possible future other than a capitalist one, and to the fact that great art, authentic and uncompromised art, can contribute to our vision of that future by increasing ‘our awareness of our potentiality’.5 This testimony, however, is not always easily reconcilable with some of the central theses of Ways of Seeing.

John Berger

Ways of Seeing is really the only one of Berger’s books in which he spells out anything approaching a ‘theory of art’, and also provides an overview of the Western tradition. The bulk of Berger’s contribution on art is neither aesthetics, nor art history, but practical criticism, i.e. his evaluative reflections upon his experience of specific works of art. What then are the central theses of Ways of Seeing! Well, firstly that European oil painting involved a way of seeing the world that was indissolubly bound up with private property. The painting, for Berger, is first and foremost a thing that can be owned and sold; post-Renaissance pictorial conventions and connoisseurship are derivatives of the oil painting’s status as property. Although traditional aesthetics have in fact been rendered obsolete by the rise of the new mechanical means of producing and reproducing imagery, he argues, they are still perpetuated because of the painting’s continuing function in exchange and as property.

Now it should be said straight away that, in part, the value of Ways of Seeing was polemical - and that it therefore suffers from the limitations of polemics. Berger was consciously offering an alternative conception of art history to that promoted by Kenneth Clark in his book and television series, Civilization. Berger raised a series of ‘uncivilized’ questions about the social and economic functions of art which Clark studiously evaded. Berger did not accept that Western art history could be legitimately portrayed as a succession of isolated men of genius. He showed that by attending to what has been called ‘the totality of the average’, the tradition of painting since the Renaissance could be revealed as being pervaded by class specific and ideological elements, deriving from bourgeois social and property relations.

In the early 1970s, these were original and contentious emphases, the more so since they were elaborated not within the enclaves of the art world or the left, but through an award-winning television series and an eminently readable, popular, paperback book. But within the art world at least, the raising of such questions became more commonplace as the decade wore on. The impact of Ways of Seeing itself certainly had something to do with this. Whatever the causes, much officially sponsored art practice, an influential school of art history, and a great deal of art criticism, tended to reduce art to ideology, tout court. Today, therefore, I think it is more important to defend a materialist version of the kernel of truth within ‘bourgeois’ aesthetics than to support the rabid left idealism purveyed by many of those who are either monstrous off-spring of Ways of Seeing, or at least products of the same cultural, common ancestors.

But before I engage in such a defence, I want to stress that one central argument of Ways of Seeing has been established beyond question: from the Renaissance until the late 19th century, some sort of ‘special relationship’ existed between art and property. This ‘special relationship’ becomes almost self-evident when one attends to the tradition as a whole, and not just to its exceptional works. No one has ever refuted this argument - and Berger may therefore be said to have delivered an historic blow to the self-conception of ‘civilized’ man. He has confirmed his own assertion: ‘We are accused of being obsessed by property. The truth is the other way round. It is the society and culture in question which is so obsessed. Yet to an obsessive his obsession always seems to be of the nature of things and so is not recognized for what it is.’6

As it happens, I think that some of the ways in which Berger describes and defines this ‘special relationship’ will require modification and revision. Berger is, of course, largely concerned with works painted before the beginning of this century; even so, I do not think he gives sufficient weight to what has been in recent years a real movement of works of art from the private to the public domain. Nonetheless, the problematic relationship persists. I came to realise just how strong it still is when, in 1975, I assisted Hugh Jenkins, then Minister of Arts, in his struggle to ensure that the proposed universal Wealth Tax was applied to works of art - with special arrangements for those works on public exhibition. Such a measure would have greatly increased access to what is often called (by those who wish to keep it to themselves), ‘The National Heritage’. In pursuing these goals, I was, of course, strongly influenced by Ways of Seeing. The sort of hysterical, irrational opposition which I encountered from the dealer-collector lobby, led by Hugh Leggatt, Denis Mahon, and Andrew Faulds, M.P., was quite unlike that provoked by any of the aesthetic battles in which I have been involved. These events confirmed for me the truth of the central argument of Ways of Seeing. Berger’s insights into the ‘special relationship’ between art and property should not be relinquished until that relationship has itself been dissolved through the historical process.

John Berger by Jean Mohr

Having said this, however, I must add that I do not think this political-economic dimension provides the only, or even the most rewarding, avenue of approach to works of art of the past. And, indeed, it is not that ‘special relationship’ which forms the subject of this critique of Ways of Seeing. My own view is that art practice and aesthetics, even in the grand era of oil painting, were not mere derivatives or epiphenomena of the work of art’s function as property. Indeed, the greater the work of art, the less it seems to be reducible to the ideology of its own time. Paradoxically, I believe that Berger’s practice as a critic, both before and after Ways of Seeing, simply assumes this point - even though Ways of Seeing (despite the fact that it attempts an overview) offers no explanation of it. Thus Berger has written numerous essays, of great brilliance, on painters from Vermeer to Monet which have not assumed that the fundamental fact of the artist’s vision and practice was a relationship to property. This should, perhaps, have caused one to question some of the arguments of Ways of Seeing. But to make this point more clearly, we now have to turn to the text itself.

Peter Fuller

Early in the book, Berger discusses the way in which learned assumptions people hold about art concerning concepts like beauty, truth, genius, civilization, form, status, taste, etc., mystify the art of the past for them. Thus he puts the constituent elements of bourgeois aesthetics into the wastepaper basket. They mystify, he says, because ‘a privileged minority is striving to invent a history which can retrospectively justify the role of the ruling classes and such a justification can no longer make sense in modern terms.’7 Thus bourgeois aesthetics are no longer of value because, the argument goes, the original authority of oil paintings (which had to do with their uniqueness and particular location) has been shattered by the development of a new technology: the various mechanical means of reproduction. (This is what I call elsewhere the 'mega-visual tradition’.8) But before he explores the effects of the rise of photography and mechanical reproduction on the way we see oil paintings, Berger gives a specific example of this process of anachronistic mystification.

He cites the way a typical academic art-historical scholar discusses Hals’ last two major paintings which portray the Governors and Governesses, respectively, of an alms house for old paupers. Berger reminds us that these were official portraits made when Hals, over 80 years old, was destitute. Those who sat for him were administrators of the public charity upon which he depended.

I want to scrutinise Berger’s discussion here. Although the academic art historian recorded the facts of Hals’ situation, he also insisted that it would be incorrect to read into the paintings any criticism of the sitters. There is no evidence, the academic says, that Hals painted them in a spirit of bitterness. He then goes on to say that they are remarkable works of art and explains why. Basically, for the academic, it is compositional elements that count. He stresses such things as the ‘firm rhythmical arrangement’ of the figures and ‘the subdued diagonal pattern formed by their heads and hands’. Berger complains that the art historian’s method transfers emotion provoked by the image from the plane of lived experience to that of disinterested ‘art appreciation’. Insofar as the art historian refers to the relationship between Hals’ painting and experience beyond the experience of art, it is in terms of Hals’ enrichment of ‘our consciousness of our fellow men’ and the close view which he gives of ‘life’s vital forces’. This says Berger is mystification: ‘One is left with the unchanging “human condition”, and the painting considered as a marvellously made object.’

Against such a reading, Berger poses what he describes in a revealing phrase as ‘the evidence of the paintings themselves’, which, he argues, renders unequivocally clear the painter’s relationship to his sitters. What is that evidence for Berger? Through reproductions he isolates the faces of three of the sitters: their expressions are allowed to speak for themselves. The academic, too, was aware of the power of these expressions, but he denied what they said. Thus he wrote about the way in which 'the penetrating characterisations’ almost ‘seduce’ us into believing that we know the personality and even the habits of the men and women portrayed. But, Berger retorts, what is this ‘seduction’ but the paintings working upon us?

John Berger

How do the paintings work upon us? Berger explains:

They work upon us because we accept the way Hals saw his sitters. We do not accept this innocently. We accept it in so far as it corresponds to our own observation of people, gestures, faces institutions. This is possible because we still live in a society of comparable social relations and moral values.

Thus Berger says Hals examines the Regent and Regentesses ‘through the eyes of a pauper who must nevertheless try to be objective, i.e. must try to surmount the way he sees as a pauper’. This rather than the juxtaposition of white and flesh tones, he says, is the ‘unforgettable contrast’ which provides the drama of these paintings.9

Here we have two opposed ways of accounting for essentially the same judgement, i.e. that these are powerful paintings which have a profound effect upon us if we attend to them. The bourgeois academic stresses the importance of formal, aesthetic and compositional elements and also the relationship between the work and culturally constant elements of human experience - ‘life’s vital forces’. Berger stresses historically specific ‘meaning’ and the fact that the painting has been constituted through particular signifying practices - observations of gesture, faces, institutions, etc., meaningful to us only because we share comparable social relations.

Regentesses of the Old Men’s Alms House, Frans Hals

One reason why I am no longer prepared to decide as unequivocally in favour of Berger as I once was is that in order to refute the ‘mystifications’ of the academic’s bourgeois aesthetics he appeals convincingly to the authority of the paintings themselves, which he reveals through reproduction of photographic details. Yet it is precisely this authority which, he maintains, modern mechanical means of reproduction - like photographs of details in art books - have shattered. Berger seems aware of this contradiction. He argues that the authority of the Hals paintings is not absolute or trans-historical. These pictures are accessible to us only because we still live in a society of comparable social relations and moral values. Hals was the first portraitist to paint the new characters and expressions created by capitalism. We, of course, still live in a capitalist society and so the meaning of these works is accessible to us.

But there is a serious contradiction here, too, because Berger goes on to argue that ‘today we see the art of the past as nobody saw it before. We actually perceive it in a different way.’ Ways of Seeing claims that later capitalism, monopoly capitalism, has so transformed perception that it is quite unlike that to which the old bourgeois aesthetic and art practice appealed. But if this is the case, then it is no use also saying that we can appreciate Hals’ paintings because our socially conditioned ‘ways of seeing’ are very much the same as those of the artist.

Clearly there is something missing from Berger’s account. Similarly, although it is of course pervaded by ideology, I do not think the academic’s account is reducible to ideology: by treating it as such, Berger comes close to throwing out the baby with the bath-water. One of the strengths of what the academic says is his attendance to the material facts of the way in which the picture has been painted. Indeed, through such attendance the academic was propelled towards conclusions at odds with the ideological preconceptions he brought to the work. That, surely, is why he reports a feeling of ‘seduction’, of the paintings working upon him, and why he feels the need to engage in all the special pleading to ‘prove’ that one of the good bourgeois governors was not drunk.

Peter Fuller

Berger says that the paintings work upon us directly through Hals’ way of seeing. There were probably many beggars in 17th century Haarlem who, if invited to paint portraits of these governors and governesses, would have seen them much as Hals did. But one is entitled to doubt whether many, if any, could have painted them anything like as well. A way of seeing is not, of itself, a way of painting. This is not a trivial or insubstantial quibble, nor just a matter of words. Berger really has nothing to say about Hals’ way of painting at all. But the bourgeois academic, albeit in a mystified fashion, recognises painting as a material process.

Of course, the academic’s ideology inhibited him from a full response to what he experienced as the paintings’ ‘seduction’. He falls back on the beauty of the paintings as objects in a way which elides that which they signify. But he does not talk about these works in complete isolation from experience beyond the experience of art. He speaks about their power in relation to what he assumes to be an ahistorical human condition. Berger dismisses this position, but perhaps there is more in it that he allows. As we saw, Berger suggested the ‘expressions’ in Hals were accessible to us because we, too, lived in a capitalist society. How then are we to explain, say, our powerful responses to the sculpture of the Laocoon, or Griinewald’s crucified Jesus? There are many works of art which come from societies where quite different ‘social relations and moral values’ prevail but which nonetheless move us powerfully and are expressive for us.

I do not think it is enough just to brush aside talk about ‘life’s vital forces’, or whatever. We have rather to stand such idealism on its head and reveal its material basis. And the kernel of truth embedded within it is that, despite historical transformations and mediations, there is a resilient, underlying ‘human condition’ which is determined by our biological rather than our socio-economic being, by our place in nature rather than our place in history. As the Italian Marxist Sebastiano Timpanaro, has said, ‘cultural continuity’ through which, as Marx observed, we feel so near to the poetry of Homer, has been rendered possible, among other reasons, by the fact that man as a biological being has remained essentially unchanged from the beginnings of civilization to the present and those sentiments and representations which are closest to the biological facts of human existence have changed little.11

A significant component in the capacity of the Hals’ paintings to move us derives from the way in which they are expressive of such ‘relative constants’ as old age (manifested through loosening of the flesh, thinning of the lips, hollowing of the eye-sockets, etc.) and the physical manifestations of power, drunkenness, arrogance and disdain. Such things are not peculiar to the emergent capitalism of the 17th century Holland, nor, I suggest, will they be unknown under socialism. This observation does not negate Berger’s reading that Hals shows us the new characters created by capitalism.

Elsewhere in Ways of Seeing Berger seems to recognize the significance of this relatively constant underlying human condition when he writes that in non-European traditions, for example in Indian, Persian and Pre-Columbian art, female nakedness is ‘never supine’ as he considers it to be in the Western fine art tradition. Berger says that if, in the non-European traditions, ‘the theme of a work is sexual attraction, it is likely to show active sexual love as between two people, the woman as active as the man, the actions of each absorbing the other’. Now Berger of course comes from a society in which ‘social relations and moral values’ are quite distinct from those prevailing in, say, ancient Persia. However he is able to make this judgement on the ‘evidence’ of the three works of art he illustrates because (whatever he says in the section on Hals) he in fact assumes an underlying human condition, embracing definite characteristics and potentialities, in this case the potentiality for reciprocal sexual love, which is not culture-specific; moreover he also appears to recognize that widely diverse sets of artistic conventions, e.g. those of Persian miniature painting and Pre-Columbian sculpture, can nonetheless be expressive of this, same area of experience in ways which are immediately accessible, indeed transparent, to those who live in a modern capitalist society.

Mithuna Couple, 1340

The problem with Berger’s account of the Hals paintings is that he lacks a fully materialist theory of expression. I see expression as involving the imaginative and physical activity of a human subject who carries out transforming work upon specific materials (in which I include both historically given pictorial conventions and, of course, such physical materials as paint, supporting surface, etc.). Expression through painting is thus in itself a specific material process: indeed, it is only through this process that the artist’s way of seeing, and beyond that of course his whole imaginative conception of his world, is made concretely visible to us. We know nothing of his way of seeing apart from that process. Max Raphael grasped this when he wrote:

Art is an ever-renewed creative art, the active dialogue between spirit and matter; the work of art holds man’s creative powers in crystalline suspension from which it can again be transformed into living energies.

This is a long way from the kind of ‘signifying practices’ approach which Berger deploys in relation to the Hals paintings; indeed, it has more in common with the bourgeois academic’s emphasis on composition and ‘life’s vital forces’. But I do not think that Raphael’s formulation betrays his position as either Marxist, materialist or empiricist.

Enough of Hals paintings. It could be said, however, that the remainder of Ways of Seeing is a sustained assault on the validity of the bourgeois academic art historian’s approach and on the bourgeois aesthetics he espouses. Berger’s argument is that aesthetics based on attendance to ‘beautifully made objects’ and the ‘unchanging human condition’ are of no value because ways of seeing have been utterly changed by the development of mechanical means of producing and reproducing images. Thus he contrasts the way in which perspective tended to make the world converge on a human subject with that process of decentering seemingly initiated by the camera, which demonstrated how ‘What you saw depended upon where you were and when. What you saw was relative to your position in time and space.’14

The invention of the camera, Berger claims, ‘also changed the way in which men saw paintings painted long before the camera was invented’. The camera destroyed the way a painting belonged to a particular place. ‘When the camera reproduces a painting’, he writes, ‘it destroys the uniqueness of its image. As a result its meaning changes. Or, more exactly, its meaning multiplies and fragments into many meanings.’15

The academic art historians mystify because they act as if that change had not come about - even when they themselves make use of the new means of production and reproduction, for example through popular art books or television. Thus Berger calls them, ‘the clerks of the nostalgia of a ruling class in decline’, not before the proletariat, but before the new power of the corporation and the state. Berger turns a blow torch upon that tenuous but central category of bourgeois aesthetics: authenticity. This, he argues, is an obsolete category in an era of mass reproduction. ‘The art of the past no longer exists as it once did. Its authority is lost. In its place is a language of images.’ This is because, ‘In the age of pictorial reproduction the meaning of paintings is no longer attached to them; their meaning becomes transmittable: that is to say it becomes information of a sort, and, like all information, it is either put to use or ignored.’16

In this situation, Berger argues, it is no longer what a painting’s image shows that strikes one as unique; its first meaning is no longer to be found in what it says, but in what it is. And what is it? Certainly not for the Berger of Ways of Seeing a crystalline suspension of creative powers. Berger insists, ‘before they are anything else, (paintings) are themselves objects which can be bought and owned. Unique objects.’ Objects whose value depends upon rarity and is ‘affirmed and gauged’ by market price.17

And so, Berger says, the attempt to erect spiritual values upon works of art is quite bogus. It is a by-product of the high market price of the painting as unique object - nothing more. Thus he reduces the notion of ‘authenticity’ to that authentication, or identification on behalf of the market - the sort of thing carried out by Sotheby’s assistants. ‘If the image is no longer unique and exclusive, the art object, the thing, must be made mysteriously so.’18

So, for Berger, the art of the past does not exist any more as it once did: instead, there is on the one hand, the world of bourgeois aesthetics which mystifies its concern with art-as- property into a wholly bogus religiosity; and, on the other, this ‘language of images’ created by the new means of reproduction. What matters now, Berger argues, is ‘who uses that language’ and ‘for what purpose’.19

Now I hope you will see why I placed so much emphasis on the lacunae in Berger’s account of the power of the Hals paintings. His lack of a materialist theory of expression leads him to talk about meaning slipping in and out of paintings in the way that an image slips on (or off) a light-sensitive film. Indeed, Berger uses the word ‘image’ to refer both to paintings and to photographs: but this disguises the fact that they are very different sorts of thing.

Photography is much closer to being a mechanical record of a way of seeing than painting. The photographer can freeze a moment of vision with the suddenness with which the window cut off the shadow of Peter Pan. Photography is merely process, a true medium. The image slides into the camera as the spirit is supposed to slip into a medium during a spiritualist seance. But painting is not like this at all. It requires a prior imaginative conception, which is not given, but made real, through the exercise of human activity, i.e. transforming work upon materials, conventional and physical. A painting is constituted, not processed. A painting is thus the material embodiment of an artist’s expressive activity in a way which a photograph is not. The Victorian view that photography, whatever it is, is not an art is by no means as silly as the photographic apologists like to make out.

And so when we make a photographic reproduction of a painting, the nature of the original is not wholly assimilated into the copy; nor can we regard the original, as Berger seems to do, as just a drained residue from which all that is of value, other than commercial value, has been detached. The reproduction refers back to an absent original. Aspects of the worked human object remain visible through the passivity of the photographic process. In New York recently I saw an exhibition of Rockefeller’s technically ‘perfect’ reproductions of his painting collection. You could buy, for example, Picasso’s Girl with Mandolin for $850, a reproduction, that is, in Cibachrome.20 But the contradiction between the flat, synthetic smoothness of the surfaces, and those of originals, reminded me that chemical and mechanical processes in and of themselves are neither imaginative nor expressive, however well (or badly) they may be able to reproduce products of the creative activity of human subjects.

Of course, we can look at reproductions assuming that they are the same sort of thing as originals. The mega-visual tradition of monopoly capitalism conditions us towards this way of seeing; one can even view originals made long before the advent of monopoly capitalism in this way. Many late modernist artists actually produce paintings or other ‘works of art’ which are in fact like reproductions.21 But I would argue that this occlusion of aesthetic sensitivity is itself ideologically determined; it involves capitulation to a reductionist way of seeing peculiar to the culture of the prevailing economic order.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres: La Grande Odalisque

In certain respects Ways of Seeing may be infected by this way of seeing. Through the concept of a ‘language of images’ the book effectively equates photographs and paintings. This is underlined by poor reproductions - much poorer than the average popular art book - in which few of those aspects of originals I have described are even remotely discernible. For example, Berger juxtaposes the expression on the face of an Ingres nude with a detail from a modern pin-up, glamour photo.23 On the page, the equation looks just. Now I am no great admirer of Ingres. Nonetheless, Ways of Seeing leaves out of account, visually and verbally, the radical differences between the two images. I would not dispute that Ingres’ paintings often contain elements of sexism. But the painstaking, imaginative and constitutive activity involved in the production of his odalisques cannot be reduced to the cynical, commercial voyeurism of glamour photography. Ingres did not pose his models and click the shutter. Even when the images are roughly equivalent, a painting, or drawing, of a naked woman implies a greater respect towards her, as a person, than a photograph. If Berger had juxtaposed his pin-up with the original, or even beside a good reproduction of Ingres, this would have been evident. Whatever our judgement on Ingres, we travesty him if we suggest that he was simply producing aids to masturbation.

Berger is unwittingly guilty of a kind of left idealism, a dissolution of painting into a chimerical world where images have no existence apart from an ideological existence. This is reflected in his view of the nature of the original after its meaning has been, according to his argument, stripped from it through the new means of mechanical reproduction. Berger sees the original as being only a social relation, i.e. a piece of property: spiritual or aesthetic values are, in his view, just a sort of golden halo, or monetary after-glow, wholly determined by a work’s property status. Thus he attacks the oil-painting medium as such for its inherent materialism, which he equates with bourgeois proprietorial values. He says that in Western oil-painting, ‘when metaphysical symbols are introduced... their symbolism is usually made unconvincing or unnatural by the unequivocal, static materialism of the painting method.’24 This he says is what makes the ‘average religious painting of the tradition appear hypocritical’. The claim of the theme is made empty by the way the subject is painted.

As an example, he reproduces three paintings of Mary Magdalene. He says that the point of her story is that she repented on her past and came to accept the mortality of flesh and the immortality of soul. But, for Berger, oil paint ‘contradicts the essence of this story’. The method of painting is incapable of making the renunciation she is meant to have made. Berger says, ‘She is painted as being, before she is anything else, a takeable and desirable woman. She is still the compliant object of the painting-method’s seduction.’251 have no wish to exonerate that sickly, Christian voyeurism which often enters into paintings of the Magdalene. However, Berger gives no weight whatever to the way the painting method demystifies the Magdalene story, it reveals, if you like, that her repentance was not what she took it to be, because immortality of the soul is not possible for us fleshy mortals whose being is limited by natural conditions, including the absolute finality of an inevitable death without resurrection. There was, if you like, a truthfulness inherent within the painting method which ruptured the religious ideology of the theme. More generally it might be said that oil painting played a significant part in the extrication of man’s selfconception from mystifying religious ideologies.

The Bathers, Gustave Courbet

Take the case of Courbet. Perhaps to a greater degree than any other painter, he manifests the materialism and concrete sensuality of this medium. But it is worth reminding ourselves how abrasive Courbet’s paintings were to prevailing bourgeois ‘visual ideologies’. Similarly, although the fat, naked woman in The Bathers is so corporeal that one can almost feel the smothering weight of her flesh, she is neither takeable, nor desirable - nor was she intended to be either. Writing about Courbet outside Ways of Seeing, Berger has convincingly related the intense physicality of his paintings to his peasant perceptions. There is no simple or necessary correlation between materialism, oil painting, and bourgeois attitudes towards property.

The realism of Western oil-painting was, however, certainly one of the ways in which men and women began to conceive of themselves in their own image, rather than God’s. Ways of Seeing castigates the materialism of this new world view: but I see it as having been historically progressive, and not only in the sense that it formed part of the ideology of what was then a historically progressive class.27 However, I am certainly not advocating a mechanical realism, or vulgar verism, as such. I would suggest that, in its very sensuality, oil painting helped to initiate an unprecedented form of imaginative, creative, yet thoroughly secular art which (though initiated by the bourgeoisie) represents a genuine advance in the cultural structuring of feeling and expressive potentiality.

Ways of Seeing makes no mention of the great romantic painters, nor yet of post-impressionism, nor of any abstract painting. But now can Delacroix, oauguin, or Rothko be accommodated within its theses? It is not just that paintings like these are so manifestly not reducible to their reproductions: their spiritual and aesthetic values too are clearly not just penumbra of their value in exchange. Man had mingled his emotional and affective life in his religious projections: oil painting was part of the process of his return to himself, or his first finding of himself. With that first finding came the emergence of a secular spirituality, based on growing awareness of the nature of the human subject and imaginative experience. The identification of the category of the aesthetic as such in the 18th century was not an ideological lie, or a fraud: it was part of this process. In his essay on Surrealism, Walter Benjamin once remarked, ‘the true, creative overcoming of religious illumination certainly does not lie in narcotics. It resides in profane illumination, a materialistic, anthropological inspiration ,..28 Profane illumination! A materialistic, anthropological inspiration! These are resonant phrases. They accurately describe what I value in Gauguin, Bonnard, or Natkin. I would suggest that any adequate ‘demystification’ of bourgeois aesthetics, having completed its discussion in terms of ideology, property values, sexism, etc. must retain an emphasis upon this vital, positive residue of sensuous mystery. This remains accessible to us as viewers through that mingling of imaginative and physical expressive work upon the surface, that material transformation by a specific human subject, which decisively and concretely differentiates the work of art from mechanically produced images. To hark back to Max Raphael, you just cannot say that the photograph, as photograph, holds man’s creative powers in crystalline suspension.

It is perhaps predictable that Ways of Seeing has nothing to say about sculpture. But if we think about sculpture for a moment the point I am making becomes clearer. Sculpture just will not disappear without residue into that ‘language of images’; a photograph of a sculpture unequivocally refers back to an original other than itself. Nor can anyone pretend that an eight inch soap-stone maquette of a great Greek marble provides anything even approximating the experience to be derived from the work itself. Marble, clay, steel and bronze are even more inherently materialist than oil paint. Yet who would contend that sculpture is a peculiarly bourgeois practice? The value of sculpture derives from elements of human being and experience which are, as it were, below ideology. Sculpture relates to our existence in a physical world of concrete, three dimensional objects in space; and to the fact that we live within the natural constraints of that relative constant of human being - the body with its not unlimited potentialities. Although painting involves a greater ideological component than sculpture, the condition of painting is more like that of sculpture than, say, photography.

Henry Moore: Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 2.

I do not want to travesty Berger’s argument: there are moments in Ways of Seeing when he recognizes the disjunc- ture between oil painting and photography. For example, in the first chapter, he writes: ‘Original paintings are silent and still in a sense that information never is.’ He points out that, ‘the silence and stillness permeate the actual material, the paint, in which one follows the traces of the painter’s immediate gestures’, and then suggests that this ‘has the effect of closing the distance in time between the painting of the picture and one’s own act of looking at it.’ I agree. And yet, in Ways of Seeing, this critical observation is no more than an aside, which seems not to fit in with the main argument.

The question of the exceptions, or masterpieces, further illuminates the weakness of that argument. Berger’s central thesis is that: ‘A way of seeing the world, which was ultimately determined by new attitudes to property and exchange, found its visual expression in the oil painting, and could not have found it in any other visual form.’ The oil painting, for Berger, is ‘not so much a framed window open to the world as a safe let into the wall, a safe in which the visible has been deposited’. And yet, having said this, Berger argues that certain exceptional artists in exceptional circumstances broke free of the norms of the tradition and produced work that was diametrically opposed to its values: thus he does not - and this is important - reduce the best of Vermeer, Turner, Rubens, or Goya to ideology.

But what is the relationship of these ‘transcendent’ masterpieces to the tradition within which they arise? How do they make the decisive and transforming if oil painting is, as Berger claims, a by-product of the bourgeois way of seeing the world? It is no use looking to Ways of Seeing for an answer to these questions. In a 1978 article, Berger wrote that the ‘immense theoretical weakness’ of Ways of Seeing was that he had failed to make clear ‘what relation exists between what I call “the exception” (the genius) and the normative tradition’. He added, ‘It is at this point that work needs to be done.’

Two years later, this problem is still clearly haunting Berger. In a review he wrote in 1980 of a book about paintings of the rural poor, Berger asks ‘Poussin relayed an aristocratic arcadianism, yes, but why was he a greater painter than any considered here?’ I think that if we re-insert materialism in the sense that I have tried to understand it in this paper, we can at least begin to talk in terms of where to look for an answer. Acknowledgement of the ‘relative constancy’ of the bodily being and potentialities of human subjects and of the fact that painting and sculpture are specific material processes (including biological processes) involving imaginative and physical work on both conventional and substantial materials allows us to establish a more secure basis for a genuinely materialist theory of artistic expression.

But, in the light of such a theory, I am sure that the over-sharp distinction between transcendent masterpieces which leap beyond ideology, and examples of the normative tradition which remain blinkered by it will be seen to be much too dualistic. Again, Berger himself seems recently to have recognised this. In the 1978 article from which I have already quoted, Berger writes, ‘The refusal of comparative judgements about art ultimately derives from a lack of belief in the purpose of art.’32 He goes on to acknowledge that there are values in art which stand apart from ideology, and furthermore that these can be weighed by a process of preferential judgement, of qualifying ‘X as better than Y’. But once you admit this, of course, you are sneaking aesthetics in by the back-door, even if you first booted them noisily out of the front door. This process of judging X better than Y just cannot be confined to labelling which are the masterpieces, and which examples of the normative tradition. The everyday tasks of criticism involve discrimination between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ elements in ‘average’ works, and between often unexceptional paintings relatively evenly matched in terms of quality. There is an infinite gradation between inept hack work, say by a Stockwell sculptor like Peter Hide, and the masterpiece, by, say, Michelangelo. Comparative judgements, aesthetic judgements, can be made all the way along this incline. In effect, the making of such judgements is the continuing search for authenticity of expression: although it has often been corrupted by base commercial motives, and distorted by overt and covert commitments to specific visual ideologies, I nonetheless refuse to allow that this way of looking is - to use Berger’s phrase - ‘ultimately determined by new attitudes to property’. Indeed, its material basis seems to me to be of a kind which will, one hopes, endure beyond the abolition of property. The making of such judgements is integral to the nature of the experience which painting and sculpture have to offer in a secular society. It is precisely this experience which I am seeking to defend. I can see no reason why, as a socialist, I should prefer the mechanical visual media, with their very different potentialities and limitations.

But here we must pause. I am saying that painting and sculpture are expressive of areas of experience and potentiality which are long-lasting in human history. Nonetheless, there is no doubt that painting and sculpture are threatened today. In recent monopoly capitalism, the mega-visual tradition (of advertising, cinema, mass-reproduction, colour printing, etc.) proliferates: its media, processes and spectacles have tended to displace or to subsume the very different kinds of practice possible through painting and sculpture.331 do not think this is merely a technical question. The occlusion of painting and sculpture involves the eclipse of significant values. I am interested in conserving these traditional media and those values.

John Berger and Tilda Swinton

However, there are many commentators on the left who go to Ways of Seeing and condemn it for what they perceive as its residues of bourgeois aesthetics. That is why Art- Language derided Berger for his residual ‘sensitivity’. Other ‘left’ critics have criticised Ways of Seeing for refusing to carry through the logic of the ‘language of images’ approach to the point where the distinction between the photograph and the painting disappeared entirely into discussion of technique; and for retaining the residue of a qualitative distinction between the masterpiece and the rest, and so forth. In these sorts of reading, Berger is characterized as a sort of simple-minded, proto-structuralist, with unfortunate ‘unscientific’, anachronistic elements which have now been dispensed with in the streamlined, fully ‘scientific’ systems of Victor Burgin and Nicos Hadjinicolau.

And indeed there is a sense in which Hadjinicolau’s book, Art History and Class Struggle, can be read as a more rigorous (or perhaps ‘insensitive’) Ways of Seeing. Hadjinicolau claims to have dispensed with aesthetics and value judgements altogether and to have cast them into ‘oblivion’. He explains away aesthetic effect as being merely the mirroring between an artist’s visual ideology and the ideology of a viewer. He even goes so far as to argue that there is no such thing as an artist’s ‘style’ because pictures produced by one person are not centred upon him; at least, not in any sense which is significant for art history. For Hadjinicolau, ‘the essence of every picture lies in its visual ideology’. He sees his task as that of relating visual ideologies to the particular class sectors from which they sprang - no more and no less.34

I have commented on Hadjinicolau’s position elsewhere.35 Here it is only necessary to repeat that he, and those like him, think that they are radicals, hard-headed socialists producing a devastating critique of bourgeois art. In fact, however, they are merely theorising with a left gloss that way of seeing which is so characteristic of late monopoly capitalism. I have demonstrated that Hadjinicolau looks at paintings as if they were advertisements. In the advertisement, the artist’s style has indeed been eliminated since the image is corporately conceived and mechanically executed. It lacks any stamp of individuality. In advertisements, the imaginative faculty is prostituted and aesthetic effect reduced to a redundant contingency. The advertisement is constituted wholly within ideology; moreover, advertising is the form of static visual imagery, par excellence, of contemporary monopoly capitalism.

Understandably, when he saw Hadjinicolau’s book, Berger was troubled. In his review of it, he mentions that it took him more than six months to come to terms with his reactions to it.36 It was in this review that Berger found it necessary to point to the ‘immense theoretical weakness’ of Ways of Seeing, to reaffirm the value of making comparative judgements about paintings, and to quote Max Raphael’s empiricist theory of art. In Hadjinicolau’s theory, Berger wrote, ‘the real experience of looking at painting has been eliminated’:

When Hadjinicolau ... equates the visual ideology of Madame Recamier with that of a portrait by Girodet, one realises that the visual content to which he is referring goes on deeper than the mise-en-scene. The correspondence is at the level of clothes, furniture, hair-style, gesture, pose: at the level, if you wish, of manners and appearances!

... But no painting of value is about appearance: it is about a totality of which the visible is no more than a code. And in the face of such paintings the theory of visual ideology is helpless

It is true that, six years before, Berger argued that the power of those Hals paintings derived from the fact that Hals enabled us to know his subjects; nonetheless, Berger explained this by something very similar to Hadjinicolau’s reduction of aesthetic effect into ideological mirroring. He claimed that we were able to appreciate these paintings only because we lived in a society of 'comparable social relations and moral values’.

Berger now warns that the path pursued by Hadjinicolau and his colleagues appears ‘self-defeating and retrograde’, leading back to a reductionism not dissimilar in degree to Zhdanov’s and Stalin’s. He points out that Hadjinicolau’s theory has elements in common with advertising in that both ‘eliminate art as a potential model of freedom’. But did not Ways of Seeing itself greatly over-stress the continuity between the Western oil painting tradition and modern advertising? After all, advertising produces no exceptions, no Rembrandts, no masterpieces, no works of genius: no advertisement ever exulted anyone, or made them aware of any but their most trivial of potentialities. Advertising, and not original painting, is always inauthentic.

In the course of this review, Berger asks what it is about certain works of art which allows them to transcend the moment in which they were made, ‘to “receive” different interpretations and continue to offer a mystery’. He adds that Hadjinicolau would consider the last word - ‘mystery’ - unscientific, but says that he does not. The problem with Ways of Seeing, however, was that it dismissed bourgeois aesthetics as ‘mystification’ and expelled its concerns - i.e. the material process of painting and composition and the relationship of art to ‘life’s vital forces’ - from the terrain of permissible left discourse about art. But, when Berger gazed into the grey reductionism of Hadjinicolau, it was precisely these ‘mystifications’ which he sought to re-introduce. Thus, in this review, he approvingly cites Max Raphael’s view that the power of historically transcendent paintings should be sought in the process of production itself: the power of such paintings, as he put it, ‘lay in their painting’. Similarly, Berger writes of the ‘incomparable energy’ which comes from this process of working the materials. Works of art, he goes on to say, ‘exist in the same sense that a current exists: it cannot exist without substances and yet it is not itself a simple substance.’38 Clearly, that bourgeois academic was not so foolish in his concerns.

The point I have been stressing throughout is that it is not enough to refuse to engage with bourgeois aesthetics, to dismiss them as if they were ideological figments and nothing else. One has rather to do to them what Feuerbach did to Christianity: reveal their material basis in the imaginative activity of an embodied human subject who realizes his expression through transforming work which he exercises to greater or lesser effect upon definite conventional and physical materials; that is, through a so-called ‘medium’ which possesses an identifiable history and tradition. In this way, I think we can begin at least to talk coherently about what Berger refers to as the scientific ‘mystery’ of a great painting, or what Benjamin might have called its ‘profane illumination’, or ‘materialistic anthropological inspiration’. Such things, I would suggest, may be reproduced through, but cannot be reduced into, the proliferating means of mechanical reproduction.

Why did Berger not see this when he worked on Ways of Seeing? He was after all a painter himself. This makes it even harder to understand the reductionism of this text. In part, I think this derives from the symbiotic relationship between Ways of Seeing and Clark’s Civilization-, the whole Ways of Seeing project insists (and rightly so) on what Clark ignored. But it fails to take on board in a materialist fashion the positive theses of Civilization. One small example: Ways of Seeing makes no mention of the fact that, in Christopher Caudwell’s phrase, ‘great art ... has something universal, something timeless and enduring from age to age’.22 Yet, of course, this is something which Civilization stuffs down our throats on page after page. But there was a much more significant influence on Ways of Seeing than the negative effects of ‘the clerks of the nostalgia of a ruling class in decline’. I am referring, oT course, to Walter Benjamin whose picture is reproduced at the end of the first chapter of Ways of Seeing, and particularly to his well-known essay, ‘The Work of Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction’.

Benjamin was a fine critic and a great writer, but he was also a man of contradictions. His thought manifested what has been called a ‘two-track’ cast.39 Susan Sontag has pointed out how, in Benjamin’s work, ‘mystical and materialist motifs were distilled into separate writings, whose precise inter-relationship remained enigmatic, often exasperatingly so, to his secular and religious admirers alike’. Today, Benjamin is acclaimed as an ancestor by both talmudic mysticists and structuralists. As Sontag points out, it is not that there are two distinct phases in Benjamin’s work; when he became a Marxist and a historical materialist, there was no inward rupture with his earlier mysticism.

Similarly, in Benjamin’s attitudes to art there was a peculiar schizophrenia. In his ‘materialist’ writings, he welcomes the destruction of the aura of the work of art by modern technology. Yet, in fact, he was an aesthete, and a compulsive collector who frequented the great auction houses.

When we are considering any part of Benjamin’s work, I think we have to relate it to this uneven and eccentric whole. One way of talking about him is to say that his materialism was not sufficiently deep. Precisely because he knew that aesthetic (and religious) phenomena could not be explained in terms of economics and ideology alone, his writing tends to be pocketed with fascinating mystical enclaves, where that which is not explicable through historical materialism (as he understood it) continues to reside in its raw, numinous, mystical or aestheticist form. To adapt his own phrase, Benjamin developed his ‘profanity’ (through his Marxism); retained his religious ‘illumination’ but failed to progress to ‘profane illumination’. It is only if one’s materialism extends down to the biological level (and not just to the socioeconomic) that one can hope to approach an adequate account of the relatively ‘ahistorical’ aspects of the spiritual (i.e. aesthetic, religious, musical, and imaginative) life of man. Benjamin, however, over-relativized the somatic, for example when he exaggerates the effects of short-term ‘historical circumstances’ on ‘human sense perception’ and effectively ignores the relative constancy of the human perceptual apparatus. Because his materialism lacks a ‘ground floor’ in physical and biological reality, Benjamin (being ‘sensitive’ rather than ‘insensitive’) retains the old idealist categories of spirit in, as it were, sealed-off compartments.

The problem is that his followers in left aesthetics tend either to internalize this contradiction (as Berger does, for example, through the contrast between Ways of Seeing and the review of Art History and Class Struggle) or they go for the ‘profanity’ alone - that is for the ‘materialism’ which does not go deeper than the socio-economic level, and reject the rest altogether. Thus commentators like Victor Burgin copy (although they do not always acknowledge) Benjamin’s castigation of those who insist on the distinction between painting and photography as holding a ‘fetishistic and fundamentally anti-technical concept of art’. But really one can only understand the status of such comments in Benjamin if one realizes that, having written them, Benjamin turned once more to those first editions, baroque emblem books, and original antiques, which he acquired in great quantities, and which preoccupied him almost to the point of distraction. There was, of course, absolutely no question of Benjamin himself making do with photographic reproductions.

Benjamin began as an aesthetic philosopher who mourned the ‘passing of old traditions’, as they were displaced by modern technology and mass society. But later Benjamin came simply to identify aura, or the ‘aesthetic nimbus’ surrounding a work of art, with property. Mechanical reproduction, however, came to stand for him unequivocally on the side of proletarianisation. But clearly, Benjamin was also aware that something was lacking in these new media. He would suddenly revert to an old ‘aesthetist’ position, as if acknowledging that he had never been able to produce a true synthesis of the two.

Stanley Mitchell has pointed out how Benjamin’s attitude to the newspaper exemplifies this contradiction.44 In his well- known essay, ‘The Storyteller’, about the Russian writer, Leskov, Benjamin contrasts the self-containing powers of the story, that most ancient bearer of wisdom, with the mere giving-out of information that is par excellence the role of the newspaper. But, in his major article, ‘The Author as Producer’ - probably written before ‘The Storyteller’ - Benjamin describes the contemporary Soviet newspaper as ‘a vast melting-down process’ which ‘not only destroys the conventional separation between genres, between writer and poet, scholar and popularizer’ but ‘questions even the separation between author and reader’. The place ‘where the word is most debased’ - that is to say, the newspaper - becomes the very place where a ‘rescue operation can be mounted’ , Thus Benjamin saw ‘technical progress’ as the basis of the author’s ‘political progress’.46 He also liked to use the image of an ‘incandescent liquid mass’ into which the old bourgeois literary, musical and artistic forms were streaming, and out of which the new forms would be cast.

Well, the new forms which Benjamin anticipated have, of course, emerged. On the one hand, we have seen since the last war a profusion of mixed media objects and activities in such things as conceptualism, performance, environmental art, etc. All this has failed to produce a single work of stature, let alone a masterpiece. It can now be said with confidence that the claims made for such innovations were, at best, vastly exaggerated. More significantly, we have also seen the development of spectacular new devices for image-making in the mega-visual tradition. Think, say, of the hologram which allows for the creation of something quite unprecedented: a fully three-dimensional image in space.46 But the development of such techniques has not fulfilled Benjamin’s prophecy. It is not just that they have proved entirely consonant with, and readily exploitable by, a monopoly capitalist culture which seeks to distort and extinguish free imaginative and creative activity on the part of those who live within it. (Guinness, for example, was deeply involved in the funding of the development of holograms: no doubt one of the first commercial uses we will see of this technique will be 40 foot high, three-dimensional Guinness bottles suspended above the Thames.) Beyond that, the very process of making a hologram does not allow for the admission of a human imaginative or physically expressive element at any point. The representation is not worked; it is posed and processed. Hence the hologram remains a peculiarly dead phenomenon when compared with the painting. I am suggesting that if Benjamin had had a more thoroughly materialist theory of expression he would have foreseen this too. The ‘incomparable energy’ of the painting is bound up with the way it is I believe that, in this situation, it is the Benjamin who defended the storyteller, Leskov, who has most to teach us. Perhaps Berger now realizes this too. Ways of Seeing, you will recall, begins with a statement which says, ‘The form of the book is as much to do with our purpose as the arguments contained within it.’ That form used such techniques as al lvisual essays, unjustified type, ‘out-of-copyright’ text, arguments in images as well as words, etc. It was close to the form of certain books - The Medium is the Message, and War and Peace in the Global Village - which Marshall McLuhan published about the same time.48 Berger’s most recent book, however, is Pig Earth49 which consists of some faultlessly told stories about the life and experiences of peasants in France. Formally, these stories are not innovative: they draw upon the traditional skills of the ‘self-preserving, self-containing powers of the story’. But there are several stories in the book which I would describe as masterpieces. I do not think the aesthetic value or political significance (for reasons which are made clear in the ‘Historical Afterword’) of the collection is in doubt. Indeed, I think they confirm my conviction that there is no more significant writer working in English today than John Berger. And personally I do not look forward to the day in which the distinction between such greater writers and their public has been thoroughly dissolved into a press which is no more than an extended reader’s page (as Benjamin envisaged it). Nor do I look forward to the day when the museums which house the finest examples of the traditions of painting and sculpture have been replaced by pinboards of reproductions - which is what Ways of Seeing suggests should ‘logically’ happen.

Notes

1. Art-Language, Vol. 4 No. 3, October 1978.

2. This is something often commented upon by my polemical opponents: for example, Janet Daley has written of my alleged ‘unlimited adulation for John Berger’, ‘Letters’ Art Monthly, No. 12, November 1977 and Suzi Gablik has described me as ‘a disciple of John Berger’s’, ‘Art on the Capitalist Faultline’, Art in America, March 1980.

3. Selected Essays and Articles: the Look of Things, Harmond- sworth: Penguin Books, 1971, p.64. And see also, ‘In defence of art’, New Society, 28 September 1978, p.702.

4. For further discussion of the reception of A Painter see my article, ‘Berger’s Painter of Our Time', in Art Monthly, No. 4, February 1977, pp. 13-16. Here, I discuss the withdrawal of this book by its publishers, Seeker & Warburg, who were also publishers of the CIA backed magazine, Encounter, which ran a hostile attack upon A Painter. Berger often failed to get the support he deserved from those who published him: in the introduction to a new edition of Permanent Red - which consists largely of his New Statesman articles from the 1950’s - Berger writes of fighting for each article, ‘line by line, adjective by adjective, against constant editorial cavilling’, London: Writers & Readers, 1979, pp.8-9.

5. Permanent Red, p. 16.

6. Ways of Seeing, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1972. p. 109.

7. Ibid, p. 11.

8. ‘Fine Art after Modernism’, New Left Review, No. 119, January- February, 1980, pp.42-59.

9. Ways of Seeing, pp. 11-16.

10. ‘Timpanaro’s Materialist Challenge’, New Left Review, No. 109, May-June, 1978, pp.3-17.

50

Seeing Through Berger

11. On Materialism, London: New Left Books, 1975, p.52.

12. Ways of Seeing, p.53.

13. The Demands of Art, Princeton, 1968, p. 187.

14. Ways of Seeing, p. 18.

15. Ibid. p. 19.

16. Ibid. p.24.

17. Ibid. p.21.

18. Ibid. p.23.

19. Ibid. p.33.

20. The Nelson Rockefeller Collection, New York, 1978, Cat. No. 57.

21.1 have discussed this in my ‘Where was the art of the 1970’s?’ in Beyond the Crisis in Art, London: Writers & Readers, 1980.

22. This is not, of course, to posit aesthetics, as such, as a transhis- torical category, but rather to suggest that the aesthetic constitutes a historically specific structuring of relatively constant, of long- lasting, elements of affective experience. For example, it seems to me that prior to the 18th century, much of that which we designate as aesthetic experience was conflated with the numinous in religious experience. But this is not, of course, to say that the affective potentialities which inform the aesthetic are reducible to the ideology of religion, nor that they can be, or ought to be, swept away with secularization. Thus I disagree with Berger when he writes, ‘The spiritual value of an object, as distinct from a message or an example, can only be explained in terms of magic or religion. And since in modern society neither of these is a living force, the art object, the “work of art”, is enveloped in an atmosphere of entirely bogus religiosity.’ The material basis of the ‘spirituality’ of works of art is not so easily dissolved. I think that it may lie in their capacity to be expressive of ‘relative constants’ of psycho-biological experience, which, however they may be structured culturally, have roots below the ideological level.

23. Ways of Seeing, p.55.

24. Ibid. p.91.

25. Ibid. p.92.

26. In my article, ‘The Arnolfini Image’, New Society, 3, November 1977, p.249,1 examine one of the earliest of all oil-paintings in this light. It is perhaps worth stressing here that most culturally signifi

Seeing Through Berger 51

cant, post Second World War, late modernist paintings have not been painted in oils, but in fast-drying, more transparent, acrylic paints which allow for instantaneous, insubstantial, transparent and accidental effects - as in the painting of Morris Louis - which oils do not. Such works, however, (even though they may well reflect the prevailing idealism of monopoly capitalist ideology and epistemology) have proved, if anything, more, rather than less reducible to values which are merely reflections of market value. (Acrylic lays itself open to being used as a process - i.e. in pouring and staining techniques - rather than as a genuine aesthetic- expressive medium.) This is another reason why we should suspect Berger’s hostility to the materialism of oil paint, as such.

For example, Berger cites what he calls ‘the exceptional case’ of William Blake, who, according to Berger, ‘... when he came to make paintings .... very seldom used oil paint and, although he still relied upon the traditional conventions of drawing, he did everything he could to make his figures lose substance, to become transparent and indeterminate one from the other, to defy gravity, to be present but intangible, to glow without a definable surface, not to be reducible to objects.’ Berger claims that Blake’s wish ‘to transcend the “substantiality” of oil paint derived from a deep insight into the meaning and limitations of the tradition’: Ways of Seeing, p.93. Now as it happens I too enjoy the imaginative vision of Blake - although I perhaps do not think he was such a great painter as Berger suggests. Nonetheless, the way Blake painted, and the techniques he used, had much to do with that particular area of experience with which he was concerned. I think that essentially he was exploring inner or psychological space through religious imagery, much as a good abstract painter now explores it through the conventions of abstraction. (Cf. my comments on Robert Natkin’s painting in Art and Psychoanalysis, London: Writers and Readers, 1980.) Such explorations have, of course, no more resistance of being treated as pieces of property than have ‘materialist’ oil paintings. But if we set up Blake’s achievement as an epitome, or exemplar, we will certainly miss the progressive character of that escape from religious ideology, cosmology and iconography to which the main tradition of oil painting bore effective witness, at least in part because, as Berger points out, of its

52

Seeing Through Berger

‘materialism’.

27. Cf. Sebastiano Timpanaro: ‘The great realist art of the (19th) century (with its “verist” developments, which were not altogether a step backward) and the great science contemporary to it, with its Englightenment and humanitarian impetus, were not a mere “fraud”. Rather they possessed a positive force precisely because of the continued existence within the 19th century bourgeoisie of motifs related to the struggle against the right, and, at the same time, because of the continued existence of a measure of autonomy among progressive intellectuals in relation to the immediate class interests of the bourgeoisie.’ On Materialism, London: New Left Books, p. 125.

28. One Way Street, London: New Left Books, p.227.

29. Berger in fact introduces two photographs of sculpture - one Pre-Columbian, the other Indian - on p.53. It is noticeable that he compares these with Western oil paintings without commenting on the radical disjuncture between the two media. This is but another example of Ways of Seeing's disregard for the material process of making art.

30. Ways of Seeing, p. 109. My arguments at this point are informed by the perceptive and penetrating criticisms of Ways of Seeing made by Anthony Barnett as long ago as 1972. (See, ‘Oil Painting and its Class’, New Left Review, No. 80, July-August 1.973, pp.109- 11) This review is reproduced as an appendix to this pamphlet. It must, however, be pointed out that in a text of this brevity, Barnett had no space to elaborate a materialist theory of expression.

31. ‘In defence of art’, New Society, 28 September 1978, p.702.

32. Ibid. p.703.

33. For further discussion of these points see my article, ‘Fine Art after Modernism’, New Left Review, No. 119, January-February, 1980, pp.42-59.

34. Art History and Class Struggle, London: Pluto Press, 1978.

35. See note 21.

36. ‘In defence of art’, p.703.

37. Ibid. p.704.

38. Ibid. p.704.

39. One-Way Street, p.31.

40. Illuminations, London: Collins Fontana Books, 1973, p.224.

Seeing Through Berger

53

As Timpanaro comments, ‘I think that one can see how every failure to give proper recognition to man’s biological nature leads to a spiritualist resurgence, since one necessarily ends by ascribing to the “spirit” everything that one cannot explain in socioeconomic terms.’ On Materialism, p.65.

41. One-Way Street, p.241 Cf. Victor Burgin’s view, ‘Conceptualism ... disregarded the arbitrary and fetishistic restrictions which ‘Art’ placed on technology - the anachronistic daubing of woven fabrics with coloured mud, the chipping apart of rocks and the sticking together of pipes - all in the name of timeless aesthetic values.’ In ‘Socialist Formalism’, Two Essays on Art, Photography and Semiotics, London: Robert Self, 1976.

42. Any one who doubts this should read the ending to ‘Unpacking My Library’, in Illuminations, and also Hannah Arendt’s introduction to this volume.

43. See ‘Introduction’ by Stanley Mitchell to Understanding Brecht, London: New Left Review Editions, 1977, p.xvii.

44. Ibid. pp.xvi-xvii.

45. Understanding Brecht, p.90.

46. See my article, ‘The light fantastic’, New Society, 26 January 1978, p.200.

47. Interestingly, Dennis Gabor, the inventor of the hologram, did not believe that his invention had rendered art obsolete. On the contrary, in his essay, ‘Art and leisure in the age of technology’, he writes, ‘Modern technology has taken away from the common man the joy in the work of his skilful hands; we must give it back to him. ’ He argued that although machines should be used to ‘make the articles of primary necessity’, the rest should be made by hand. ‘We must revive the artistic crafts, to produce things such as hand-cut glass, hand-painted china, Brussels lace, inlaid furniture, individual bookbinding,’ etc. In Jean Creedy, ed., The Social Context of Art, London: Tavistock, 1970, pp.45-55.

48. Of course, I do not intend to suggest that the ideas and arguments of Berger are as ephemeral as those of these books, nor yet that new forms in book-making can never be effective, or convincing. Berger’s study, made with photographer, Jean Mohr, of European immigrant workers, A Seventh Man„Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1975, remains an exemplary achievement. The danger

54

Seeing Through Berger

arises when technical innovativeness is put forward as the only model of ‘political progress’ in literature or the arts.

49. London: Writers and Readers, 1979.

50. Ways of Seeing, p. 30.