Klein’s theories, evidently, were in this respect a real advance on Freud’s. Klein gave a centrality to the infant’s early relationship with the mother, to the degree that, as Brierley put it, Freud’s more orthodox followers found it ‘difficult to reconcile Melanie Klein’s assumption that the infant very soon begins to love its mother, in the sense of being concerned for her, with Freud’s conception that in the earliest months the infant is concerned with its environment only in relation to its own wishes.’37 Nonetheless, despite Klein’s formal assurances to the contrary, it remains true that in her system the course and character of this relationship is determined not so much by the quality of the mothering which the child receives as by the way in which the child plays out its innate, instinctual ambivalence. As we have seen, Klein was concerned with what she took to be the working out of an instinctual opposition between love and hate, which was not greatly affected by the nature of the environment. In general, Klein emphasised, indeed overemphasised., orality, feeding, etc. As Guntrip puts it, ‘Mrs Klein states that “object-relations exist from the beginning of life”. . . but this seems to be something of an irrelevance; it does not matter much whether they do or not if they are merely incidental to the basic problems. ’38

A decisive step in psychoanalysis, however, was the replacement of dual instinct theory, whether of the Freudian or Kleinian variety, by a full object relations theory, i.e. by a theory in which the subject’s need to relate to objects plays a central part. Psychoanalysis arrived at this focus in Britain long before it did so elsewhere. (Only during the 1960s did some American analysts also become involved in this area of work.) The way in which this came about involved a number of disparate, and often seemingly incompatible strands and elements. Flere, I can only sketch a few of the more significant.

Some came from the serious critiques of psychoanalysis which were being elaborated outside the movement itself. For example, in the 1930s, analysts were often involved in theoretical jousting with members of the Tavistock Clinic. (Glover has written that within the British Psychoanalytic Society, ‘suggestions that a closer contact might be made even with more eclectic medico-psychological clinics, such as the Tavistock Clinic, were frowned on.’)39 Nonetheless, at the Tavistock, J. A. Fladfield, who was far from totally rejecting analytic findings, argued against Freud’s auto-erotic conception of infancy that the fundamental need of children was for protective love. In the early 1930s, Ian Suttie was one of Hadfield’s assistants. Suttie died at the age of 46, in 1935, but the following year his critique of Freud’s psychology, The Origins of Love and Hate, was published.

Suttie provides a systematic account of man as a social animal, whose object-seeking behaviour is discernible from birth. Suttie abandons Freud’s concept of Narcissism arguing that ‘the elements or isolated percepts from which the ‘‘mother idea” is finally integrated are loved (cathected) from the beginning.’ Thus Suttie found it possible to speak of the infant’s love for an external object, the mother, from the earliest moments of life. This was not sentimentalisation of the infant-mother relationship; he identified its biological basis clearly:

‘I thus regard love as social rather than sexual in its biological function, as derived from the self-preservative instincts not the genital appetite, and as seeking any state of responsiveness with others as its goal. Sociability I consider as a need for love rather than as aim-inhibited sexuality, while culture-interest is derived from love as a supplementary mode of companionship (to love) and not as a cryptic form of sexual gratification.’41 Suttie was not approved of by the psychoanalytic establishment in his life-time. Today, however, many of the criticisms he made of Freud—including his observations of the latter’s ‘patriarchal and antifeminist bias’—are very widely accepted, even within the psychoanalytic movement itself. Indeed, by the 1940s, hostility between the Tavistock and the Institute of Psychoanalysis was diminishing. For example, John Bowlby was analysed by Joan Riviere, one of Klein’s foremost followers; Klein herself was one of his supervisors when he was a trainee analyst. In 1946, Bowlby joined the Tavistock, without relinquishing his psychoanalytic associations. Bowlby was further strongly influenced by the work of ethologists, especially Tinbergen and Lorenz. Bowlby acknowledges a debt to Suttie, but in his own work he elaborated a. thorough-going critique of Freudian instinct theory: ‘in the place of psychical energy and its discharge, the central concepts are those of behavioural systems and their control, of information, negative feedback, and a behavioural form of homeostasis.’42 Bowlby strongly opposed the idea that the infant’s relationship to the mother was based on primary need gratification, such as the wish for food. Bowlby emphasised the need for ‘a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship’ with the mother ‘in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment’. He held that the ‘young child’s hunger for his mother’s love and presence was as great as his hunger for food.’4' Although retaining psychoanalysis as his frame of reference, Bowlby drew on a mass of empirical data from other disciplines. The fact that he stands at the intersection between psychoanalysis, behavioural studies, ethology, biology, and contemporary communications theory should have rendered his work of enormous significance to all of us on the left who are looking for a rigorously materialist account of the early infant-mother relationship. Instead, socialists have tended to revile his work without attending to it but that is another story.

Other influences were also inflecting the unique course which psychoanalytic theory was taking in Britain. You may remember that in my last seminar, I referred to Sandor Ferenczi, a close colleague of Freud’s until his latter days, and Klein’s first analyst. Ferenczi was the leader of the psychoanalytic community in Budapest, until his death in 1933. Guntrip has accurately described the differences between Ferenczi and Freud, differences which were to have tragic consequences for the former:

‘Ferenczi recognised earlier than any other analyst the importance of the primary mother-child relationship. Freud’s theory and practice was notoriously paternalistic, Ferenczi’s maternal- istic. His concept of "primary object love” prepared the way for the later work of Melanie Klein, Fairbairn, Balint, Winnicott, and all others who to-day recognize that object-relations start at the beginning in the infant’s needs for the mother. Ferenczi held that this primary object-love for the mother was passive, and in that form underlay all later development.’44 Many of those gathered round Ferenczi developed his approach. Hermann, for example, pointed towards such components in the infant’s relation to the mother as clinging and clasping, which could not be accommodated within the traditional Freudian perspective. Alice and Michael Balint began to develop a more radical critique of Freud’s theory of narcissism, but Hermann’s observations enabled them to progress beyond Ferenczi’s essentially passive conception of the infant’s relation to the mother, to a fuller characterisation of this ‘archaic’, primary object-relation. In the Balints’ view, the infant was ‘born relating’, even if its mode of loving was egotistic.45 Early object relations possessed autonomy from erotogenic activities. The Balints came to live and work in Britain, where their ideas had a considerable influence'among some Kleinians.

But, within Kleinian circles, parallel critiques and extensions of classical theory had already sprung up independently. Among the most significant was that put forward by W. R. D. Fairbairn, an analyst who, in the middle and late 1930s, was strongly under the influence of Klein. However, between 1940 and 1944, Fairbairn published a series of controversial papers— including, ‘A Revised Psychopathology of the Psychoses and Psychoneuroses’ of 194 1 46—in which he essentially revised psychoanalytic theory ‘in terms of the priority of human relations over instincts as the causal factor in development, both normal and abnormal’. Fairbairn described libido as not pleasure-seeking, but object-seeking; the drive to good object relationships is, itself, the primary libidinal need. In the words of Guntrip, his most devoted disciple:

‘From the moment of birth, Fairbairn regards the mother- infant relationship as potentially fully personal on both sides, in however primitive and undeveloped a way this is as yet felt by the baby. It is the breakdown of genuinely personal relations between the mother and the infant that is the basic cause of trouble. ’47 Fairbairn, like Klein before him, was something of a systems builder: I do not think that there are many analysts today who make use of all his bizarre terms and constructs. Nonetheless, there can be no doubt that Fairbairn’s work—together with the influences coming from Budapest, and the ‘Tavistock’ critiques of psychoanalysis—paved the way for a great deal of original work in the post-Kleinian tradition on the nature of the infant- mother relationship. D. W. Winnicott, Marjorie Brierley, Marion Milner, Harry Guntrip, John Padel, Masud Khan, and Charles Rycroft were among those who contributed substantially to the development of object-relations theory. Evidently, I am talking about a heterogeneous tradition, one which was characterised by internal contradictions, polemics, and controversies—nonetheless, in my view this tradition represents the most constructive development within psychoanalysis, and that which, incidentally, has the most to tell us about the nature of creativity, visual experience and their enjoyment.

In our next seminar, we will be examining the work of D. W. Winnicott in detail, in relation to certain types of abstract art. Here, I merely wish to point out that it is in the work of Winnicott and his colleagues that we find a focusing upon a transient phase of development which is between that of the ‘subjectivity’ of the earliest moment, in which even the mother’s breast is assumed to be an extension of the self, and the more ‘objective’ perceptions of later childhood. As Winnicott himself put it:

‘I am proposing that there is a stage in the development of human beings that comes before objectivity and perceptibility. At the theoretical beginning a baby can be said to live in a subjective or conceptual world. The change from the primary state to one in which objective perception is possible is not only a matter of inherent or inherited growth process; it needs in addition an environmental minimum. It belongs to the whole vast theme of the individual travelling from dependence towards independence.’48

I will have more to say about this phase next time; meanwhile, I would just point out that it is characterised by tentatively ambivalent feelings about mergence and separation, about being lost in the near, of establishing and denying boundaries about what is inside and what is outside, and concerning the whereabouts of limits and a containing skin, so that the infant, while beginning to recognise the autonomy of objects, nonetheless feels ‘mixed up in them’ in a way in which the child or adult does not.

Now all this work has been done since that moment when the psychoanalysts ‘tittered’ at Bell for saying that ‘if Cezanne was for ever painting apples, that had nothing to do with an insatiable appetite for those handsome but to me unpalatable fruit.’ To say that for Cezanne (or Bell) the apple was a symbol of the breast tells us rather less than nothing: to say, however, that the kind of space which Cezanne constructs, with its ambivalences between figure and environment, foreground and background, and between concepts and perceptions, is in some way related to the way in which the infant relates himself to the breast, the mother and the world is to say a great deal. It is in the light of this later analytical work that we can best begin to arrive at a materialist anlaysis of what happens in the outstanding paintings of the modern movement. Through this work, I can give some theoretical spine to my deeply held feeling that there are moments in the now threatened modern movement which are not just examples of kenosis and epilogue, but genuine extensions of the capacity of painted images, and spatial organisations, to speak of certain aspects of human experience in ways which simply could not be reproduced in other media, where space cannot be imaginatively and affectively constituted in the same way.

Winnicott himself was very much aware of correspondences between his findings and the work of many writers and artists; unfortunately, however, few of those involved in theoretical aesthetics, or critical work, have attended to his texts. Indeed one has to confront the fact that although British ‘object relations’ theory is well known among clinicians, therapists and educationalists, it has had very little impact upon culture beyond those specific disciplines. Perry Anderson, editor of New Left Review, commented on this in his historic 1968 text, ‘Components of the National Culture’.4'’ Although he acknowledged that the British School of psychoanalysis was ‘one of the most flourishing’ in the world, he pointed out that its impact on British culture in general has been virtually nil. Psychoanalysis ‘has been sealed off as a technical enclave: an esoteric and specialized pursuit unrelated to any of the central concerns of mainstream “humanistic” culture.’50 Anderson relates this to his ‘global’ analysis of British culture, to the failure of the British bourgeoisie to elaborate a world-view, to the resultant ‘absent centre’ of British culture, and its resistance to alien ‘impingements’. His analysis is one with which, by and large, I am in substantial agreement. But why has the British achievement in psychoanalysis been so widely ignored on the left which opposes itself to that ‘mainstream’ whose lacunae Anderson describes? I have not, after all, noticed much discussion of Klein, Winnicott, Rycroft, etc. in the pages of New Left Review.

I cannot attempt a complete answer to this question here, but I would like to throw out two indications. Firstly, I am convinced that what Suttie called ‘a taboo on tenderness’ operates among many intellectuals, a taboo which is characterised by a radical distrust of those areas of experience which, by their very nature, cannot be fully verbalised. (I have in mind here, for example, the tendency of certain Althusserian writers on art to seek to replace the experience of the work with a complete, they would say ‘scientific’, verbal account of it.) Winnicott wrote that ‘the individual gets to external reality through the omnipotent fantasies elaborated in the effort to get away from inner reality.’51 There are those on the left who never stop elaborating such omnipotent fantasies in the attempt to obliterate the encroachments of a subjectivity which they deny. This is one reason why so many who have any interest in post-Freudian psychoanalysis scuttle across the channel to the structural- linguistic models through which Lacan endeavours to describe the infant-mother relationship. In effect, the very forms in which Lacan casts his work, with all its pseudo-algebraic pretensions, are a denial of the affective qualities of precisely that which they purport to describe, whereas Winnicott’s ‘metaphoric’ mode does not allow one any such escape into the irrational ‘rationality’ of a closed system.

There is another, related reason which is perhaps more excusable: in many of these psychoanalysts there is a trace, and sometimes more than a trace, of philosophical idealism. What they discovered about the early infant-mother relationship sometimes led them, for example, to direct or indirect apologetics for religion. (This was true of Brierley, Guntrip, and Suttie.) But the point is that these writers and researchers were uncovering the material, biological, roots of such phenomena as religious and aesthetic experience: by this, I mean, they were exposing their rootedness in a certain definite, developmental phase. There are times in which, lacking a historical materialist perspective, some of these writers tended to conflate the specific social, cultural religious and artistic forms within which such experiences and emotions were structured and accommodated with those experiences and emotions themselves. (This was never true of Winnicott, or of Rycroft who has, for example, drawn attention to the way in which certain theological concepts were, prior to developments in object relations theory, the most adequate accounts of certain kinds of experience, for which non-theological explanations are now possible.) However, in developing an ideological critique of those social and cultural forms, the Marxist left has, in my view, sadly neglected the major advances made by the British psychoanalytic school into what it is that is structured through such forms. This is one reason why, as yet, there is no adequate Marxist analysis of religion, music, or abstract painting.

In this respect, the Marxist left may be said to resemble Freud himself. We have already had occasion to note how Freud dreaded any potential contamination between psychoanalysis and ‘mysticism’. But again, it is important to ask whether in his opposition to certain definite cultural forms, such as religion, and his pathological indifference to others, such as music, and non-representational art, Freud was manifesting not just his commitment to ‘science’ and rationality, but also his denial of significant areas of his own experience.

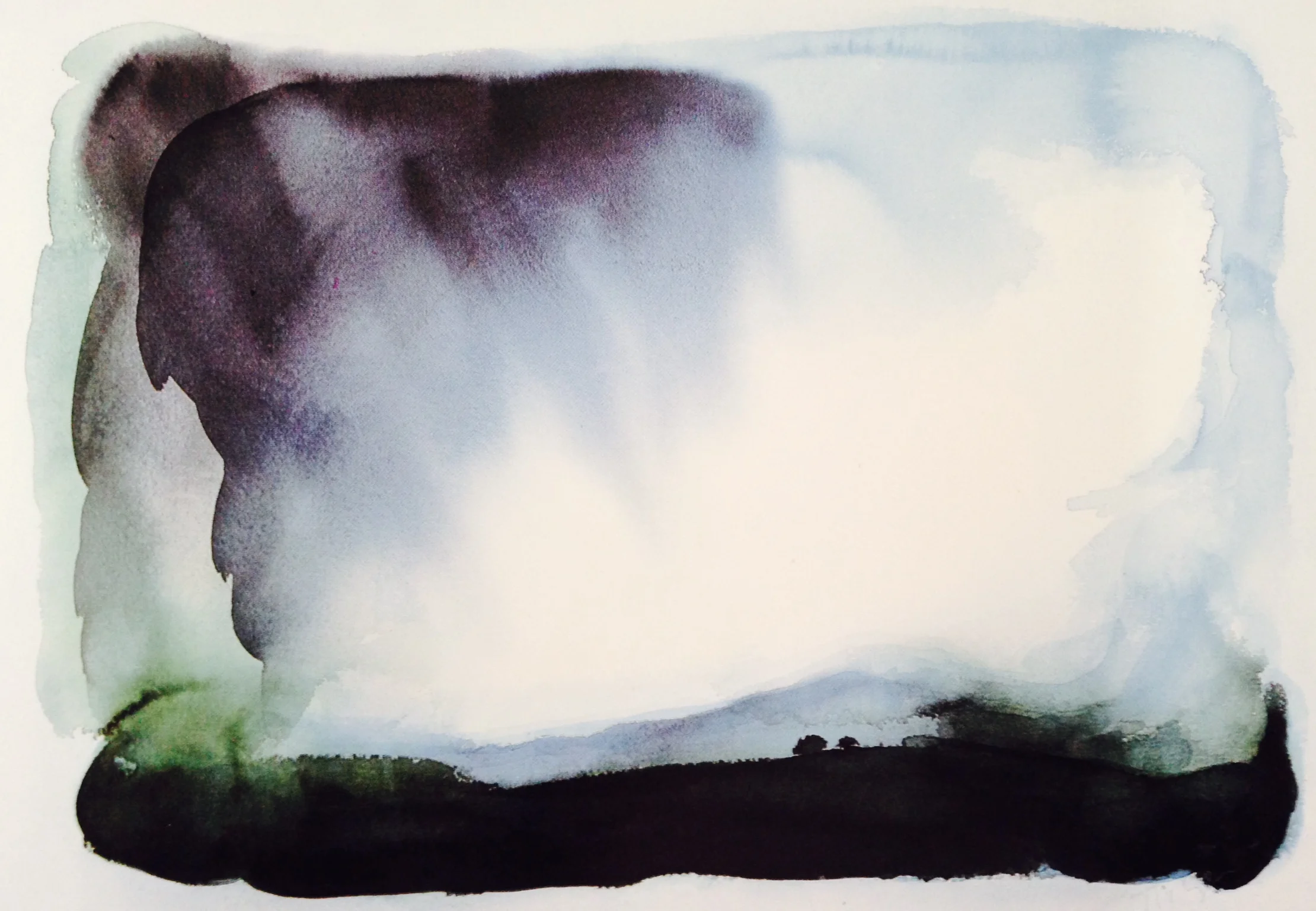

For example, in his discussion of religion, Freud talked about a mystical state which he described as a feeling of being at one with the universe, which he correlated with feelings of dependency and being overwhelmed. Freud described this feeling as ‘oceanic’—a term he got from a friend—but confided that he had never, himself, experienced anything like it. Freud explained this feeling as a regression to the early infantile state when the child’s ego is not differentiated from the surrounding external world. Anton Ehrenzweig has observed that Freud is thus claiming that the feeling of union is no mere illusion, but the correct description of a memory of an infantile state otherwise inaccessible.52 In telling us that he never experienced such emotions Freud is indicating an area of his personality which would appear to be subject to defensive denial: he is pointing to a failure in his historic self-analysis. The oceanic feeling of union does not only manifest itself in mystical or religious forms: it seems to be an important element in certain types of auditory and visual aesthetic experience, too— experiences to which, as we know, Freud was notoriously insensitive. On all such experiences and areas of human life, Freud has almost nothing of interest to say: his silence, I am sure, may be correlated with his indifference to and denial of the real nature of the infant-mother relationship, as described in the work done by the British object relations school over the last quarter of a century.

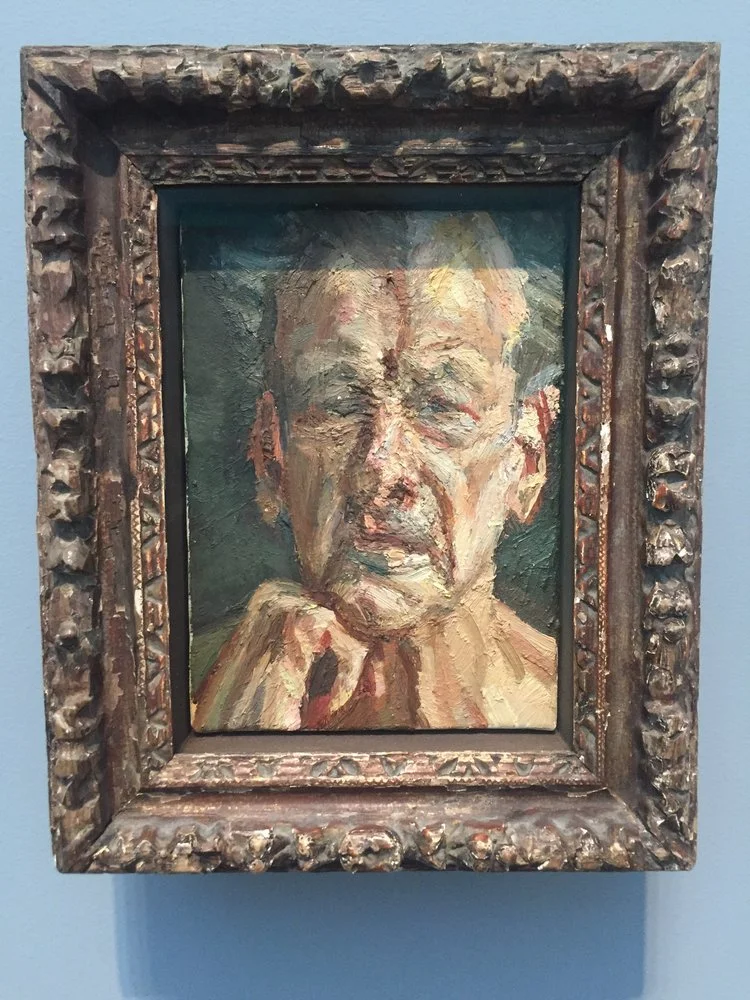

Freud, you will remember, admired the Moses of Michelangelo, but had nothing to say about those ‘unfinished’ or ‘incomplete’ works—now almost universally more widely admired—in which the figure seems to be struggling to free itself from (or is it to submerge itself back into) the matter out of which it has been wrought. Evidently, this was partly culturally as well as psychologically determined: in the 19th century, Michelangelo’s late drawings were widely regarded as merely the products of a senile old man who had lost his touch; today, there are many who would acclaim these figures with multiple, ebbing outlines as among the finest which the artist did. My point is that these drawings speak of significant areas of experience which, in the past, tended to be either locked within the mystifications of religion, or denied altogether.

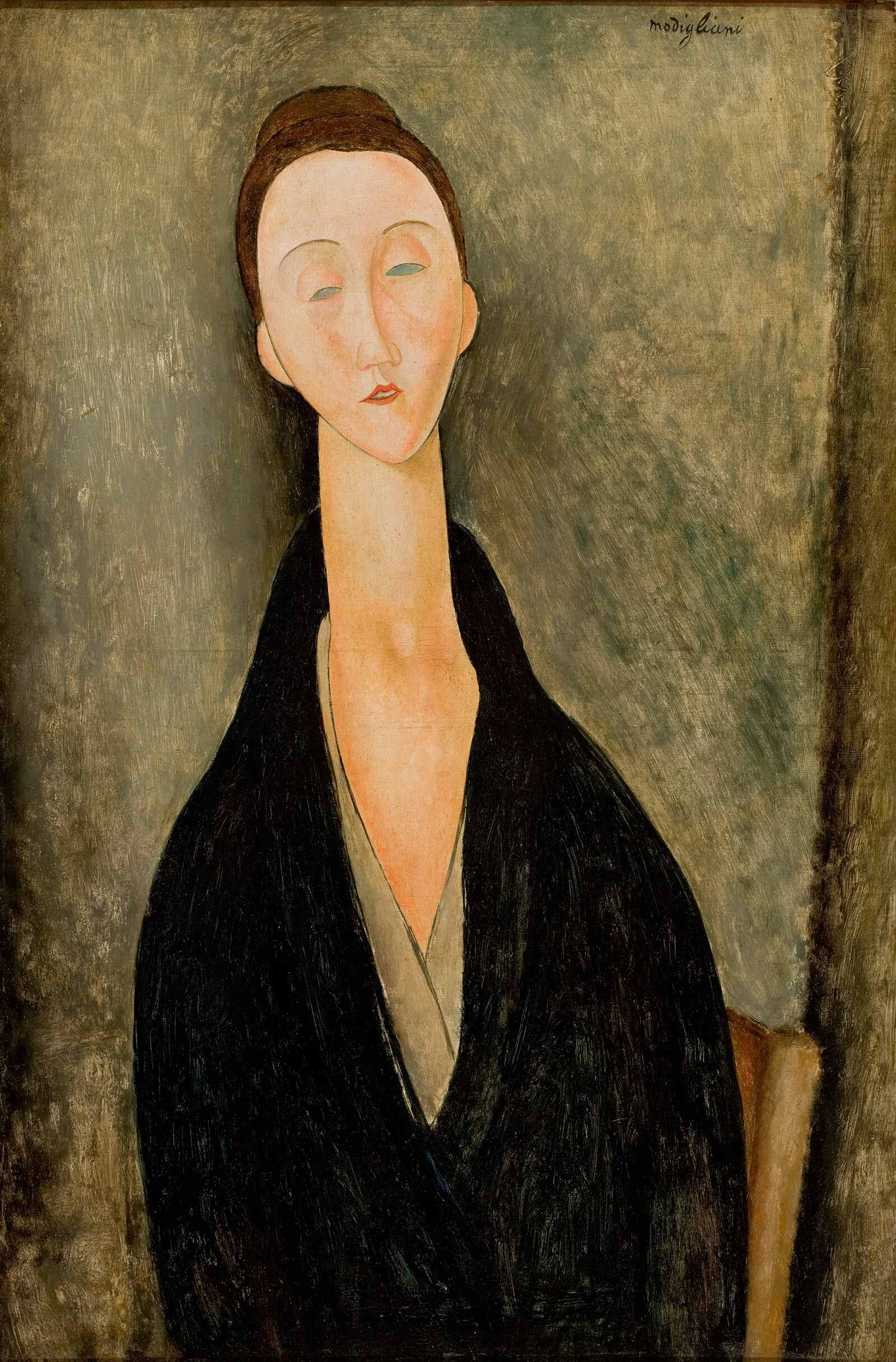

Perhaps I can demonstrate this by referring to a writer whose ‘taste’ and whose psychoanalytic theories can both meaningfully be described as being somewhere between Freud’s and my own, E. H. Gombrich. Gombrich, you will remember, can certainly appreciate the art of Post-Impressionism; he has, howev.er, never enjoyed abstract painting: In his essay, ‘Psycho- Analysis and the History of Art’,53 Gombrich draws heavily upon Michelangelo, Crucifixion. The ideas of Edward Glover, and especially on the latter’s study, ‘The Significance of the Mouth in Psycho-Analysis’.54 This was written before Glover was deeply influenced by Melanie Klein. (Later, you may remember, he polemicised strongly against her: when her ideas obtained partial acceptance within the British Society, Glover, who had been among its most influential members, resigned and joined the Japanese Society instead.) Gombrich here suggests a wholly oral ontogenesis of aesthetic taste, describing ‘oral gratification as a genetic model for aesthetic pleasure’. Gombrich proposes two polarities in taste, the ‘soft’ and the ‘crunchy’, which, through Glover’s ideas, he correlates with the ‘passive’ and the ‘active’, and with ‘sucking’ and ‘biting’ oral modes respectively. Gombrich implies that the ‘soft’ is more primitive and infantile; while the crunchy corresponds with sophisticated, civilised taste.

To make his point, Gombrich takes an atrocious academic painting of the Three Graces by Bonnencontre, and, as he puts it, tries to ‘improve the sloppy mush by adding a few crunchy breadcrumbs’. He does this by photographing the picture through wobbly glass. ‘You will agree,’ he writes, ‘that it looks a little more respectable’. And, indeed, he is right. It does. Gombrich explains this by saying, ‘We have to become a little more active in reconstituting the image, and we are less disgusted.’'6 He repeats the experiment by taking another photograph through the same glass at a greater distance, so that the figures are even more shadowy, and their outlines blurred and dissolved. He comments, ‘By now, I think, it deserves the epithet “interesting”. Our own effort to reintegrate what has been wrenched apart makes us project a certain vigour into the image which makes it quite crunchy. ’

Gombrich goes on to say:

‘. . . this artificial blurring repeats in a rather surprising way the course that painting actually took when the wave of revolt from the Bouguereau phase spread through the art world. ’57 He comments on the blurring achieved by Impressionism which ‘demands the well-known trained response—you are expected to step back and see the dabs and patches fall into place’; and Cezanne, ‘with whom activity is stimulated to even greater efforts, as we are called upon to repeat the artist’s strivings to reconcile the demands of representation with obedience to an overriding pattern.’58 Interestingly, all Gombrich’s examples— the Bonnenconue, Impressionist, and Cezanne’s—here are of the female nude. His conclusion is that whereas ‘taste may be accessible to psychological analysis, art is possibly not’.

Now evidently there is much that is true in Gombrich’s account, but what is wrong with it is his underlying assumption that the infantile relationship to the mother is instinctual in character, that is, realised exclusively through the mouth and the search for oral satisfactions and reducible to a matter of taste in a limited, oral sense. I doubt whether the reason why the blurred Bonnencontre is more ‘interesting’ now is simply, or even at all, due to a maturer preference for a later oral phase, for biting over sucking, for crunchy over soft. There are hints that Gombrich, too, realises this because the way he develops the notions of ‘active’ and ‘passive’ with reference to the pleasure to be derived from the attempt to ‘reintegrate what has been wrenched apart’ suggests the kind of Kleinian notion of the restoration of internal objects which we discussed at the end of our last talk. (The differences between the Bonnencontre original, and the ‘wobbly glass’ versions can be compared with those between the Hiram Powers sculpture and the Venus de Milo.) But we, ourselves, are now ready to go beyond even such Kleinian accounts. I would say that the reason the distorted Bonnencontre is more ‘interesting’ has to do with its capacity to begin (however thinly and vaguely) to evoke that critical phase, to which Winnicott referred, between experience as wholly subjective, and the achievement of objectivity and perceptibility, when the child is relating to another whose otherness is at once recognised and denied; when the existence of the boundaries (outlines) or limiting membranes of the self and of its objects are at once perceived and imaginatively ruptured. An explanation of this order allows us to see the developments in Modernism, to which Gombrich refers, as much more than a change of taste, or the addition of a few breadcrumbs to mush. We can begin to take into account the affective expressiveness of pictorial spatial organisations themselves. In comparison, Gombrich is merely engaging in a slightly more sophisticated variant of that psychoanalytic ‘tittering’ in front of Cezanne’s apples than that which so understandably irritated Bell.

Indeed, I hope that you will now be able to see that we are ready to leave the Kleinian aesthetics which, up until now, have served us so well. Adrian Stokes, you will remember, found elements belonging not only to the ‘depressive position’, but also to the prior ‘paranoid-schizoid’ position in both artistic creativity and aesthetic experience. For Stokes, the sense of ‘fusion’ was combined, though in differing proportions, with the sense of ‘object-otherness’. This led to criticism from more orthodox Kleinians, who felt that, by associating aesthetics and creativity with the ‘paranoid-schizoid’ position, and its mechanisms, Stokes was characterising them as regressive. But Winnicott rejects the notion of a ‘paranoid-schizoid’ position, with its overtones of primary insanity, and disjuncture. Indeed, in the work of many of those involved in the British ‘object relations’ tradition—as Anton Ehrenzweig put it—‘the concept of the primary process as the archaic, wholly irrational function of the deep unconscious’ underwent a ‘drastic revision’.5'' Marion Milner once wrote that this revision ‘has been partly stimulated by the problems raised by the nature of art’,60 not least, of course, by much of the art of the modern movement.

We do not have time to go into all the implications of these revisions of psychoanalytic thinking on the nature of the primary process here. Suffice to say that Freud’s view of them as something menacing in later life, to be defeated by ‘science’ and the Reality Principle, or Klein’s view of them as an analog of madness have been increasingly eclipsed. To cite one specific example, Ehrenzweig drew attention to a distinction between ‘the narrow focus’ of ordinary attention, and the ‘diffused, wide stare’ which had its origins in the infantile gaze. This has considerable importance in our understanding of the difference between, say, perspective painting and abstract expressionism. Rycroft has done more work demolishing the view that the primary and secondary processes are mutually antagonistic, and that the primary processes are maladaptive. He has pointed out how the attitude of psychoanalysis towards these processes derives from a paradox:

‘Since psycho-analysis aims at being a scientific psychology, psycho-analytical observation and theorizing is involved in the paradoxical activity of using secondary process thinking to observe, analyse, and conceptualise precisely that form of mental activity, the primary processes, which scientific thinking has always been at pains to exclude.’61 Rycroft, however, emphasises the importance of primary process thinking in many imaginative, creative, and aesthetic endeavours. One might say, therefore, that the re-appropriation of these modes within the modernist tradition was not simply a regressive evasion of the world.

In her theoretical paper on art, Milner says:

. .the unconscious mind, by the very fact of its not clinging to the distinction between self and other, seer and seen, can do things that the conscious logical mind cannot do. By being more sensitive to the sameness rather than the differences between things, by being passionately concerned with finding “the familiar in the unfamiliar” (which, by the way, Wordsworth says is the whole of the poet’s business), it does just what Maritain says it does; it brings back blood to the spirit, passion to intuition.’62 But Milner is not suggesting that the primary processes belong in adult life to a separate category, of no use in understanding the real, as opposed to the imagined or imaginary world. Indeed, she says that ‘it was just this wide focus of attention’, as described by Ehrenzweig, which made the world ‘seem most intensely real and significant’ for her. Thus, we might say, those spatial organisations constructed by the early modernists are not merely enrichments of nostalgic fantasy life, but also potentially of our relationship to the world itself. (This seems to me the real secret of Cezanne.)

At one point, while she was trying to overcome her inability to paint, Milner found herself thinking about a statement of Juan Gris, who once defined painting as being ‘the expression of certain relationships between the painter and the outside world. ’ ‘I felt,’ writes Milner, ‘a need to change the word “expression” of certain relationships into experiencing certain relationships; this was because of the fact that in those drawings which had been at all satisfying there had been this experiencing of a dialogue relationship between thought and the bit of the external world represented by the marks made on the paper. Thus the phrase “expression of’ suggested too much that the feeling to be expressed was there beforehand, rather than an experience developing as one made the drawing. And this re-wording of the definition pointed to a fact that psychoanalysis and the content of the drawings had forced me to face: the fact that the relationship of oneself to the external world is basically and originally a relationship of one person to another, even though it does eventually become differentiated into relations to living beings and relations to things, inanimate nature. In other words, in the beginning one’s mother is, literally, the whole world. Of course, the idea of the first relationship to the outside world being felt as a relationship to persons was one I had frequently met with in discussions of childhood and savage animism. But the possibility that the adult painter could be basically, even though unconsciously, concerned with an animistically conceived world, was something I had hardly dared let myself face.

Looked at in these terms the problem of the relation between the painter and his world then became basically a problem of one’s own need and the needs of the “other”, a problem of reciprocity between “you” and “me”; with “you” and “me” meaning originally mother and child. ’63 And now that I have exposed all the fragments of my statue—at least all of those which I have to hand—it only remains for me to attempt to fit them into place. I am suggesting that there is something significant in common between Milner’s difficulties with perspective and outline in her attempts to learn to draw; the shift in my taste from Ingres’ linearly cloistered figures to the paintings of Bonnard, Rothko and Natkin; the kind of space which begins to manifest itself in paintings with the eruption of the modern movement—say in Cezanne’s trees touching and not touching those distant mountains; and poor, dim-witted Mr. Bell’s exquisite raptures on his cold white peaks of art.

I am suggesting that what these phenomena have in common is a relatedness to a significant area of experience, that pertaining to a critical phase in the infant-mother relationship; I do not conceive of that relationship as ‘a matter of taste’, or instinctual orality, so much as a determinative moment in the self’s discovery of, and exploration of its relationship to, its world. The nature of the ‘primary processes’ in this early phase is no longer necessarily opaque to us: ‘object-relations’ theory, as it developed in the post-Kleinian tradition in Britain, permits us intellectual and affective understanding of this infant-mother relationship. It also causes a revaluing of the ‘primary processes’, and of the part which they play in the realisation of the full potentialities of the relationship of the self to others and its world. To speak crudely, in the medieval era, the ‘primary processes’ constituted the lived relation of self to the world (e.g. in religious cosmology). But, particularly with the 19th century emphasis upon ‘Science’, rationality, and inevitable progress, these areas of experience tended to be excluded from the dominant culture, or locked into mystified enclaves—such as religion.

Not even classical psychoanalysis succeeded in penetrating this terrain. In part, this was the result of the deficiencies of Freud’s self-analysis, his inability to reach back towards the affects pertaining to this determinative phase in the infant- mother relationship, and his consequent misconstruing of the nature of the primary processes. But the world-view of that culture within which Freud was enmeshed reinforced his prejudices and defences, his ambiguous belief in the value of ‘science’ over and above that of the imaginative faculties. However, 1914-1918 saw the final shattering of that worldview. Those areas of experience which had been denigrated, distorted, eclipsed or excluded flooded back—sometimes in their most archaic and mystifying forms. For example, in the later 19th century Liberal Protestantism in Germany, from Ritschl to Harnack, had effectively purged Christianity of its religious content, through a theology of immanence in which Jesus was nought but a particularly well-behaved bourgeois. The First World War shattered this ‘progressive’, middle-class faith, and gave birth to a ‘mystical’ revival, exemplified in Otto’s The Idea of the Holy of 1917, and a ‘Crisis Theology’ (soon to be known as ‘Neo-Orthodoxy’) which re-asserted the transcendence, and unutterable otherness of God. At this time, too, a species of cosmic idealism flooded back into physics as the Newtonian conception of the universe seemed to collapse.

In art, as we have seen, the validity of the focused system of perspective was shattered. But the Modernist enterprise does not seem to me to have been just an escape, or a retreat into idealism and ‘subjectivity’ (although, of course, there were elements within it that could be so characterised). It was almost as if the painter had to go back to experiences at the breast (and before) in order to find again, in a new way, his relationship to others and the world. This, I think, was what happened in the best elements of Modernism—and it was what Bell responded to, though he structured his response in terms of ‘aesthetic emotion’ and ‘significant form’.

Perhaps I can here elaborate an analogy of a kind which I would suspect if it was put forward by anyone except myself! Michael Balint describes a certain type of pathology as a manifestation of what he calls ‘basic fault’. In these instances the patient’s whole mode of being in the world, of relating to it, and to others is faulty and false; he maintains this can only be overcome if the patient is allowed to regress to a state of dependence on the analyst, in which he can experience a ‘new beginning’. (This corresponds to a distinction Winnicott makes between ‘true’ and ‘false’ self.) In a certain sense, 1914-1918 exposed the ‘basic fault’ of European culture: the kenosis of modernism (at least in certain of its aspects) may be compared with the individual patient’s necessary regression towards a position from which a ‘new beginning’ (in this instance, presumably, a new realism) was possible. Although he does not draw this comparison, Balint himself implies something similar in his 1952 paper, ‘Notes on the Dissolution of Object- Representation in Modern Art’. Balint refers to the disappearance of ‘the sovereign, sharply defined and delineated object’ from both physics and art; but he ventures the view:

‘The present narcissistic disappointment and frightened withdrawal, degrading the dignity of the object into that of a mere stimulus and laying the main emphasis on the sincere and faithful representation of the artist’s subjective internal mental processes, will very probably give way gradually to a concern for creating whole and hearty objects. (This is meant in a purely descriptive sense and no value judgement is either implied or intended with it.)64 Balint goes on to ‘the unavoidable integration of the discoveries of “modern art” with the demand of “mature love” for the object.’65 But this is already to look forward to the subject of our final seminar, that of the ‘promise’ inherent within certain of the most emptied-out examples of full abstraction.