MODERN ART chronicles a life-long rivalry between two mavericks of the London art world instigated by the rebellious art critic Peter Fuller, as he cuts his path from the swinging sixties through the collapse of modern art in Thatcher-era Britain, escalating to a crescendo that reveals the purpose of beauty and the preciousness of life. This Award Winning screenplay was adapted from Peter’s writings by his son.In September 2020 MODERN ART won Best Adapted Screenplay at Burbank International Film Festival - an incredible honor to have Shane Black one of the most successful screenwriters of all time, present me with this award:

As well as Best Screenplay Award at Bristol Independent Film Festival - 1st Place at Page Turner Screenplay Awards: Adaptation and selected to participate in ScreenCraft Drama, Script Summit, and Scriptation Showcase. These new wins add to our list of 25 competition placements so far this year, with the majority being Finalist or higher. See the full list here: MODERN ART

by Peter Fuller, 1981

This paper was first given in Newcastle-upon-Tyne Polytechnic in January, 1981, when I was Critic-in-Residence there. Subsequent versions of it were also delivered at the Ruskin School of Drawing in Oxford—and at the National Association of Teachers in Further and Higher Education’s Conference, in London, in February 1982. Newcastle University (as opposed to the Polytechnic) was an important centre for the development of the ‘Basic Design’ theories here criticized. When published in Art Monthly this text produced an intemperate response from one of the principal Newcastle ‘Basic Design’ protagonists—Richard Hamilton. I have not felt it necessary to amend my remarks in any way following Hamilton’s intervention.

I have no need to remind anyone involved in education that we live in an era of rabid governmental cut-backs. Unfortunately, there are those in this situation who look upon art education as a sort of optional icing, or even a disposable cherry, on the top of a shrinking cake. Government education cuts have fallen disproportionately upon the art schools: the future of art education in this country is politically vulnerable in a way in which, say, the education of chemical engineers is not.

Peter Fuller

I want to begin by saying that I am an unequivocal defender of art education in general and of Fine Art courses in higher education in particular. I do not make this defence so much in the name of art as in that of society. I believe that ‘the aesthetic dimension’ is a vital aspect of social life: our society is aesthetically sick; without the art schools it would be, effectively, aesthetically moribund.

What do I mean by an aesthetically healthy society? The anthropologist, Margaret Mead, once noted that in Bali the arts were a prime aspect of behaviour for all Balinese. ‘Literally everyone makes some contribution to the arts,’ she wrote, ‘ranging from dance and music to carving and painting.’ This, of course, did not mean that the arts were reduced to the lowest common denominator, or anything of that sort. As Mead puts it, ‘an examination of artistic products from Bali shows a wide range of skill and aesthetic qualities in artistic production.’

If Mead’s account is correct, I would certainly be prepared to say that the Balinese lived in an aesthetically healthy culture: that is one in which individual expression (in all the manifold imaginative and technical variations of each of its specific instances) can be freely realized, through definite, material skills, within a shared symbolic framework. This surely is what Ruskin and Morris were getting at when they contrasted Gothic with Victorian culture. Basically, I find myself in agreement with Graham Hough when he points out in his book, The Last Romantics, that, in the nineteenth century, a spreading bourgeois and industrial society left less and iess room for the arts. As Hough puts it, the arts ‘no longer had any place in the social organism.’

Once, the term ‘art’ had referred to almost any skill; but as so much human work was stripped of its aesthetic dimension, ‘Art’ with a capital ‘A’ increasingly became the pursuit of a few special individuals of imagination and ‘genius’, a breed set apart: ‘Artists’. Of course, high hopes were invested in the new means of production and reproduction—from the mechanization of architectural ornament, to photography, mass printing, and eventually television and holography. But these things did not even begin to fill that hole in human experience and potentiality which opened up with the erosion of ‘the aesthetic dimension’ and its retraction from social life.

Portrait of Peter Fuller by Maggi Hambling

And so the art education system today is not just the most extensive form of patronage for the living arts in this country: it is the soil without which the arts would just not be able to survive at all. I would go so far as to say that the primary task of the art schools in general, and of Fine Art courses in particular, should be to hold open this residual space for ‘the aesthetic dimension’. In one sense, this is a conservative function—like preserving the forests, or protecting whales. But in another it is profoundly radical: it involves the affirmation that a significant dimension of human experience is endangered in the present, but could come to life again in the future, and once more become a vital element in social life. In other words—and this really is at the root of all the problems in art education—it is the destiny of the art schools, if they are successful, to stand as an indictment of that form of society in which they exist and upon whose governments they are dependent for all their resources.

In such a situation, of course, it is inevitable that art education should be fraught with contradictions and conflicts about its aims and functions. Although the battle lines are rarely clearly drawn, the underlying struggles are usually pretty much the same: they are between those who are basically ‘collaborationist’ in outlook towards the existing culture, and those who perceive that the pursuit of ‘the aesthetic dimension’ involves a rupture with, and refusal of, the means of production and reproduction peculiar to that culture. This may sound a bit complicated, so let me give you a specific example: some of you may have read in the press some months ago about the battles at the Royal College of Art in London. Basically, these were about the ‘usefulness’ of painting and sculpture as taught in the Fine Art Faculty.

Richard Guyatt, who was then the rector, wanted the College to become a servant of industry. Guyatt had a background in advertising and the Graphic Arts: indeed, he was personally responsible for such triumphs of modern design as the Silver Jubilee stamps, the Anchor Butter wrapper, and a commemorative coin for the Queen Mother, issued in 1980. Predictably, when Guyatt was subjected to pressures from the Department of Education and Science, he responded by trying to drive the College along in a commercial, design orientated direction. As The Guardian commented, one question under debate was ‘whether scarce resources formerly offered to scruffy painters and sculptors should be switched to designers who might make some concrete contribution to Britain’s export drive.’

Inevitably, Guyatt clashed heavily with Peter De Francia, Professor of Painting, who clearly thought that it was preferable to teach students to create a ‘new reality’ within the illusory space of a picture, rather than to encourage them to design coins so ugly that consumers would want to get rid of them quickly in return for the slippery delights of New Zealand dairy products, or whatever. The battle was long and hard fought. Fortunately, given the support of his students, De Francia was able to win in the end: he remains as Professor of Painting, whereas Guyatt is no longer rector. But I have not brought this up as an example of academic intrigue: the Royal College affair was symptomatic of that struggle which has constantly to be waged against the anaesthetizing encroachments of the cultural collaborationists, even within the art schools themselves.

Of course, it is not often that the values of a major painter are so starkly pitted against those of a designer of coinage and butter-wrappers. In this situation, I think that most people who are involved, in any way, with the Fine Arts would have little doubt about where we stood. But, of course, it is not always as simple as that, and a major problem in recent years has been the betrayal of the ‘aesthetic dimension’ within Fine Art courses themselves. Indeed, I do not think that it is just a matter of protecting and conserving Fine Art courses against the Guyatt’s of this world, but rather one of reforming and rebuilding them, above all of undoing some of the damage that has been done, especially since the last war.

You could, I think, see something of this damage in a recent exhibition ‘A Continuing Process: The New Creativity in British Art Education, 1955-65’, which told the story of the establishment of the so-called ‘basic design’ courses, for Fine Art students, and of the way in which they proliferated until they became, effectively, the orthodoxy for a higher education in art. ‘Basic design’ was pioneered at the University in Newcastle by Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton, and elsewhere, along rather different lines, by Harry Thubron and Tom Hudson.

The fundamental premises of ‘basic design’ are not easily identifiable; the various artist-teachers involved in the movement pursued different, and sometimes contradictory, emphases. But this much can be said with certainty: they are all united negatively. ‘Basic design’ involved a wholesale rejection of the academic methods of art education, rooted in the study of the figure and traditional ornamentation. As Dick Field has written, the watchword of the ‘basic design’ pioneers was ‘a New Art for a New Age’, and they set out to be deliberately iconoclastic towards what had become established academic methods of teaching art.

David Thistlewood, who organized the exhibition, has written that, as a result of ‘basic design’, ‘The aims and objectives underlying a post-school art education in this country have changed utterly during the past twenty-five years.’ He says that ‘Principles which seem today to be liberal, humanist and self-evidently right would have been considered anarchic, subversive and destructive as recently as the 1940s.’ He claims that what used to exist, the old academic system, was ‘devoted to conformity, to a misconceived sense of belonging to a classical tradition, to a belief that art was essentially technical skill.’ For decades before the arrival of ‘basic design’, Thistlewood complains, there had been unhealthy preoccupations with drawing and painting according to set procedures; with the use of traditional subject- matter—the Life Model, Still-Life, and the Antique—witn the ‘application’ of art in the execution of designs; and above all with the monitoring of progress by frequent examinations. But, he claims, the advent of the new methods of teaching art constituted a ‘revolution’ against all that: in its place there now exists ‘a general devotion to the principle of individual creative development.’

But was the advent of ‘basic design’ such an unmitigatedly beneficial occurrence? Far be it from me to defend the old academicism; nonetheless, I believe that British art education of the last quarter of a century has, in general, been peculiarly disastrous and the sort of thinking that went into ‘basic design’ has had a lot to do with this. It is not just that today, instead of providing an alternative to academicism, ‘basic design’ is itself a new academicism (i.e. it is just about as ‘revolutionary’ as Leonid Brezhnev!) I also believe that, from the beginning, it exerted a restrictive and finally ‘collaborationist’ influence. I think we really need to get rid of most—although not quite all—of the attitudes which it embodies if art education is to become truly healthy.

Evidently, I cannot do justice to ‘basic design’ philosophy here, but I want to draw attention to two of its most fundamental assumptions—which I believe to be wrongheaded. The first of these is the attitude to ‘Child Art’, which one finds in Pasmore and Hudson in particular, and which has had an extraordinary effect upon the way in which most art students have been taught in recent decades. To put it crudely, the ‘basic design’ view seems to be that the intuitive and imaginative faculties of the child are repressed by culture, and the primary function of art education of adolescents should be to restore that earlier pristine state. Thus the spontaneous and intuitive productions of the child are often supposed to be paradigms of human creativity. All art is assumed to aspire to the condition of infantilism.

I have to be careful here because I believe that enormous gains were made through the recognition of a ‘natural’ potentiality for creativity in all children. As a result of the ‘Child Art’ movement, which began in the nineteenth century and gathered pace throughout the first half of the twentieth, art slowly came to play an integral part in nursery, primary and secondary school education. The ‘Child Art’ movement underlined the fact that learning was not just a matter of the acquisition of knowledge and functional skills: creative living also involved the development of imaginative, intuitive and affective faculties of the kind which play such a conspicuous part in the making of art. And so this movement stressed the fact that the capacity for creative work is an innate, biologically given, potentiality of every human being, of whatever age, class, culture, or condition. This affirmation seems to me to have an importance extending far beyond its immediate applications in nursery, primary, and secondary school education. Nonetheless, there is a great gulf between the acknowledgement of the child’s capacity for creativity, and describing that creativity as some kind of exemplar, or epitome, for adult art.

Indeed, I have been forced to the conclusion that, healthy as the ‘Child Art’ movement may have been, in itself, it was also symptomatic of a profound cultural loss: that is the loss of what I have called the ‘aesthetic dimension’ in adult, social life, of the space for imaginative and fully creative work among those who are no longer children. Surely, in an aesthetically healthy society, the capacity for creative work should develop continuously from the spontaneously individualistic self- expressions of the child (shaped by the proccesses of psycho- biological growth and development) into more complex, meaningful, and fully social (but no less creative) productions of the adult. I came to realize that we have tended to fetishize ‘Child Art’ to such a degree only because aesthetic creativity is so rare in our society at other developmental stages.

To put it another way: I suggested earlier that Bali was an ‘aesthetically healthy’ society. In what sense could a Balinese painter recognize an infant’s immature aesthetic activities as any kind of model for his own? Think, too, of those forms of aesthetic creativity manifest in, say, Amerindian rugs, the Parthenon frieze, Islamic tiles, or those magnificent carvings of leaves which cluster round the tops of the Gothic pillars in the Chapter House of Southwell Minster. Such forms of art do not seem to me, in any way, to contradict the growth of ‘individual creative development’; but, in such instances, that development has been allowed to mature, to rise beyond and above the infantile, through an adult, social, aesthetic practice.

Even when such practices were driven out of the everyday fabric of life and work, painting and sculpture permitted the creation of a new and definite reality within the existing one, an illusory, re-constituted world within which the aesthetic dimension could survive, mature, and truly develop. Again, as soon as we ask in what sense ‘Child Art’ could have provided an exemplar for, say, Michelangelo, Poussin, Vermeer, or Bonnard, we begin to realize that the celebration of ‘Child Art’ may have reflected an extension of human experience in one direction, but it also revealed its diminution in another.

So one of my quarrels with recent art education in general and with ‘basic design’ in particular is that by venerating ‘Child Art’ as the paradigm of human creativity and expressive activity, they have not, as they claim, served the cause of ‘individual creative development.’ Rather, they have simply institutionalized the fact that we live in the sort of society in which such development tends to be arrested at the infantile level: i.e. everyone engages in the arts in our society, but only up until the age of about thirteen. In my view, higher education in the Fine Arts should involve the search for ways of breaking out of this aesthetic retardation rather than the celebration of it. The child may paint solely through bold, impulsive gestures, covering his surface in a matter of seconds: but that, to my mind, is no good reason why art students up and down the country should seek to imitate him.

Richard Hamilton

But I think that ‘basic design’ type teaching reflects the aesthetic retardation of our culture in another way, too. What I have in mind here is manifest in, say, Richard Hamilton’s contempt for the traditional art and craft practices, his obsession with consumer gadgetry and functional machinery, and his preoccupation with what he calls ‘the media landscape’ —that is with such things as advertising, fashion magazines, pulp literature, television, photography and so forth, which he thinks have replaced nature as the raw material for the attention of the serious artist. More generally, much recent art teaching has tended to foster the view that in order to be a Fine Artist today, some sort of radical accommodation with the mass media—that is with what I call the ‘mega-visual tradition’—is necessary. For Hamilton was not just the Daddy of Pop: he was also the Grandaddy of all those who believe that Fine Art practices should be displaced, or at least deeply penetrated, by such things as ‘Media Studies’, video-tape, and so on, and so forth.

I said earlier that, despite claiming to be concerned with ‘individual creative development’, ‘basic design’ type teaching just institutionalized the retardation of such development, which is so typical of our culture, and I think that Hamilton’s uncritical preoccupation with these non-Fine Art media proves my point. For the proliferation of these media seems to me to be one of the major reasons why infant creativity within our culture so rarely flowers into an adult aesthetic practice. These forms of mechanical production and reproduction of imagery are fundamentally anaesthetic: they do not allow for that ‘joy in labour’, that expression of individuality within collectivity through imaginative and physical work upon materials, within a shared and significant symbolic framework, which is characteristic of aesthetically healthy societies—like Bali, as described by Margaret Mead, or Ruskin’s idealization of ‘Gothic’. Indeed, that ‘mega-visual’ tradition, and those mechanical processes, which Hamilton celebrated are a major reason why ‘individual creative development’ tends to be so inhibited. But instead of challenging the aesthetic crisis, and proposing alternatives to it, the new art education simply mirrored it, encouraging the art student either to regress to an infantile aesthetic level, or to immerse himself in the anaesthetic practices of the prevailing culture. Behind this basic contradiction it is not difficult to detect the ghost of Bauhaus, the last movement within modernism which enshrined the belief that individual creativity was fully compatible with the methods of mass-mechanical production. I believe this to be nonsense: it is a simple historical fact that Bauhaus regressed, in its design practices, into the dullest of dull functionalisms—with appalling effects on the whole modernist tradition in architecture and design. I think we may have to accept that William Morris was right; machines may be useful to us for all sorts of things. They are, however, fundamentally incompatible with true aesthetic production.

I think the point I am making about the way in which ‘basic design’ type teaching internalizes this aesthetic crisis in our culture is clearly visible if you look at the development of its two principal Newcastle proponents, Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton, as artists: ‘A tree is known by its fruit.’

In my view, Pasmore’s art has regressed steadily since the late 1940s, when he began to apply the kind of principles in his own art which he later inflicted upon his students. I have no doubts about my judgement that his painting of a nude woman, The Studio of Ingres, which he made in 1945-7, is far better than anything that came later: it was made when Pasmore was still under the influence of the ‘objective’ methods of the Euston Road School. I was shocked by the regression from this level of work to the blobs and daubs of Pasmore’s recent work, in his recent retrospective. I really could see no qualities in many of these works at all; indeed, they looked precisely like the offerings of someone who had been seduced by the paradigm of Child Art, and pursued it in a literalist way. Pasmore’s amoeba-like forms, and his barely controlled techniques, like running paint over tilted surfaces, splattering, fuzzing and so forth, remind one—if you will forgive the expression—of the work of a grown-up baby.

Hamilton took the other route. With his bug-eyed monsters from film-land, his quasi photographic techniques, and his modified fashion-plates, he began to offer little more than parasitic variations of ‘mega-visual’ images. All the awkward promise, and half-formed sensitivity of his early pencil drawings vanished into slick, collaborationist practice. I have a lot more respect for Guyatt’s coinage and butter-labels, than for Hamilton’s recent adaptations of Andrex toilet tissue advertisements: although neither have any grasp of the ‘aesthetic dimension’, at least what Guyatt does has some sort of social use.

However, I do not just wish to criticize two individuals. Over the last decade, I have been into art schools all over the country, and (until recently at least) I noticed how frequently the work done divided into two, for me, almost equally unsatisfactory categories. On the one hand there were the slurpy, ‘gestural’ abstractionists, and on the other what I would characterize as ‘media-studies’ styled modernists. I have tried to show you how these two approaches seem to me to be just two sides of the same rather debased art-educational coin, which deprives art students of those real, material skills through which their creativity might develop into something more than that of the child’s, and other than that of the sterile forms of the ‘mega-visual’ tradition.

Maurice de Sausmarez, a spokesman for the ‘basic design’ approach, has said that the new art education set out to teach ‘an attitude of mind, not a method’. This view, unfortunately, gained official sanction when the 1970 Coldstream report on art education declared that studies in Fine Art should not be too closely related to painting and sculpture, because the Fine Arts ‘derive from an attitude which may be expressed in many ways.’ There is, however, an enormous gap between an attitude in the mind, and the realization of a great painting: and I do not, myself, think that it is possible to teach art except through definite material practices in which the student is encouraged to achieve mastery.

In 1973, Charles Madge and Barbara Weinberger, two sociologists, published a book, Art Students Observed, which was in effect a study of the way in which the new art education was working out in practice. They reported that ‘half the tutors and approaching two-thirds of the students of certain art colleges agreed with the proposition that art cannot be taught.’ Understandably, the authors then asked, ‘In what sense, then, are tutors tutors, the students students, and colleges colleges? What, if any, definitionally valid educational processes take place on Pre-Diploma and Diploma courses?’ There can be few involved in art education who have not asked themselves these questions at some time or other. The authors reported, that nearly all tutors ‘rejected former academic criteria and modalities in art’, but none had any others to put in their place.

My own view is that it is quite useless to go on teaching this peculiar mixture of infantilism, media studies, and Fine Art ‘attitudes’ in post-school art education. Of course, I believe that a relatively unstructured situation is healthiest for young children, making their first tentative explorations into drawing and painting. (In such cases, the structuring comes from innate developmental tendencies, rather than from ‘culture’.) Nonetheless, it is at least worth pointing out that many infant art teachers are now beginning to argue in favour of a more ‘directed’ approach much earlier than has been fashionable in recent decades, and to look again at the creative value of practices like copying, which were once abhorred as being completely sterile.

I believe that, by the time the student reaches post-school level, he or she simply cannot develop creatively without the acquisition of culturally given skills. That is why Fine Art education should be based much more firmly and unequivocally than it is at present in the study of painting and sculpture. Imagination and intuition are indeed essential to the creation of good art; but these faculties are impervious to instruction. There are, however, many others integral to the creation of good art which can be taught. Drawing is, of course, the most significant of these: and, rather than ‘the Fine Art attitude’, I would like to see drawing of natural forms, especially the human figure, reinstated as the core of an adult education in Fine Art.

Of course, as soon as one mentions the figure, those who have been brought up within the ideology of the new art education raise the bogey of ‘academicism’. But this ignores a well-established tradition of anti-academic figure drawing in this country which, for my money, has produced far more impressive results as an educational method than ‘basic design’, or anything resembling it. I am referring to that tradition which emerged in the Slade at the end of the last century, under the influence of that great teacher, Henry Tonks. Tonks saw that there was nothing wrong with learning to draw from the figure, as such, although there was everything wrong with the stereotyped togas, and mannerist pretensions in which the traditional academics swathed this practice. Tonks held that drawing should always be both poetical and objective, but he recognized that only the objective part could be taught. Before becoming an art teacher, Tonks had practised as a surgeon: he denied there was such a thing as outline, and stressed the structural aspects of the figure. If you mastered the direction of bones, Tonks taught, you had mastered contour, too. Tonks certainly taught a method, and not just an attitude of mind. He wanted students to spend all day, every day, in the life room. Now according to today’s art educational theorists, he ought thereby to have strangled any conceivable talent that came his way. But he didn’t. Those pupils interested in the ‘objective’ aspect of painting certainly thrived under his influence: William Coldstream, himself a doctor’s son, went on to elaborate his own clinically ‘factual’ system of figure painting. But those drawn towards the ‘poetical’ dimension often flourished, too. Thus Stanley Spencer—than whom few can be considered more imaginative —learned what he needed to realize his great compositions in Tonks’ life room, too. Similarly, Bomberg, who laid an almost equal emphasis on imaginative transformation and empirical exactitude in his pursuit of ‘the spirit in the mass’, benefited from Tonks’ rigorously methodical approach . . . And then there were Bomberg’s pupils, painters like Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff, and Denis Creffield, all of whom show a similar respect for the empirical and imaginative dimensions, and also for the specific traditions and potentialities of their chosen medium: painting. Work of this calibre is, to me, altogether more impressive and worthwhile than anything produced in the wake of latter-day Pasmore, or Hamilton.

But I do not want to be misunderstood: I am not saying that students should be shut up in the life-room all day iong and made to do ‘Tonksing’ against their will. I am however saying that what makes painting a particularly valuable and exceptional form of work is that, in it, the intuitive and imaginative faculties do not stand in opposition to the rational, analytical and methodical: rather, they can be combined together in ways which most work in our anaesthetic society disallows. This, if you like, is the excuse for painting, the reason that, when it is good, it stands as a kind of ‘promise’ for the fuller realization of human potentialities. And I am saying that precisely in order that the student can be helped to realize his individual creative potentialities to the fullest, art education must begin to concern itself with the ‘objective’ end of the expressive continuum much more than it has done in recent years.

It is nature which has somehow disappeared from recent art educational practices. I prefer a much wider view of natural form than that implicit in Tonks’ approach. There are even elements of ‘basic design’ which I would like to see preserved and extended: the most significant of these is the attention which Pasmore and Hamilton, at least in the early days, gave to the structure and growth of natural organisms—like crystals. My only objection to their approach here is that it was much too narrow: the student should be encouraged to attend to the full gamut of natural forms, beginning with the figure, and extending outwards.

Ron Kitaj

Tonks once said that he had no idea what the body looked like to those who had not studied anatomy. I believe that before students involve themselves in the microscopy advocated (though not in fact much practised) as an element in ‘basic design’, they ought to achieve a real knowledge of the structure of the human body itself, of anatomy. It is no accident that Ron Kitaj, who is one of the best figurative artists working in this country, is also one of the very few who has actually conducted an autopsy, and worked with a cadaver. Of course, that guarantees nothing: but, equally, it remains true that neither Leonardo, nor Michelangelo, could have achieved what they did without this sort of knowledge. But I would go further than this: I believe that the practice of drawing needs to be supplemented with certain knowledges, beyond anatomy, which the present art schools simply do not teach. Why, in complementary studies, does one find so little instruction for Fine Art students in such topics as metereology, botany, geology, and zoology: in order to offer an imaginative transformation of the world in one’s work, one must first attend to that world, and above all to the visible forms through which it is constituted. But most art students grow up with an impoverished conception of reality which owes more to cigarette advertisements and sociological theory (with perhaps a dash of art history) than to empirical perception and the natural history of form. Personally, I think you would learn much more about the business of painting if you spent an hour, say, drawing quietly in a natural history museum rather than studying that ‘media landscape’ which seduced Hamilton, or ‘expressing yourself’ in abstract, like a child.

I have put a lot of emphasis on painting and sculpture. What about the ‘other media’? In an ‘aesthetically healthy’ society, the aesthetic dimension permeates throughout all work, and extends to every part of the social organism, regardless of class and condition. But we do not live in such a society: and painting and sculpture, alone, offer this promise of a new reality, realized within the existing one. That is why I think that the priority of Fine Art education should be the preservation and encouragement of these practices.

Nonetheless, I also believe that it should be part of a Fine Art education to learn about, and to practice, other aesthetic pursuits—namely those offered in the whole field of the ornamental and decorative arts. Indeed, this is where recent education has gone so wildly wrong: it has encouraged Fine Art students to engage in the anaesthetic practices of the prevailing culture, not only the sorts of things that interested Hamilton, but the whole field of video, applied photographic processes, mixed media, etc., etc. I think it would be much more valuable if they were encouraged to look at things the other way round: i.e. to think about taking fully aesthetic, creative practices out into that aesthetically sick society.

Peter Fuller

Dennis Gabor was the man who invented the new medium to end all new media, the hologram which offers a fully three- dimensional image. But he certainly did not think that he had rendered traditional aesthetic pursuits obsolete. He once wrote, ‘Modern technology has taken away from the common man the joy in the work of his skillful hands; we must give it back to him.’ Gabor went on, ‘Machines can make anything, even objects d’art with the small individual imperfections which suggest a slip of the hand, but they must not be allowed to make everything. Let them make the articles of primary necessity, and let the rest be made by hand. We must revive the artistic crafts, to produce things such as hand-cut glass, hand- painted china, Brussels lace, inlaid furniture, individual bookbinding.’ These are sentiments with which I agree entirely; and there would be nowhere better to start this revolution than on Fine Art courses.

I am not, of course, suggesting that students should set off along that narrow path which leads to a potters wheel in Cornwall: a better paradigm of the sort of thing I have in mind would be say, the revival of mosaic in Newcastle, linked to an officially sponsored project to produce wall decorations for the new Metro system. The project, as I understand it, is that well- known artists will design mosaics, and that students from the Polytechnic Fine Art Department will assist in the making of them. I think that the arts schools could, and should, do much more in this sort of direction. Indeed, in short, rather than allowing Fine Art values to be assimilated by mega-visual tradition, art schools should be encouraging students to take aesthetic values out into that anaesthetic culture: otherwise, one of the most significant of all human potentialities risks being lost altogether.

1981

This interview was originally published in Authority Magazine 06/23/2020

The journey of becoming an actor, truly going through the rigors will put you in positions where you are forced to have self-awareness, compassion, and to deal with your demons, most people are simply not challenged in that way and remain in an unconscious state. Some people will see someone chasing their dreams and try to sabotage them. I don’t get that, I see motivated, passionate people and I want to help them.

It’s important to notice whether people are coming at you with support and encouragement or whether they’re seeking to ‘take you down a peg’, I’m not one for ‘tall poppy syndrome’ culture, it’s tough out there, hard for everyone nowadays, if someone does well at something they should be encouraged. That’s my take on it.

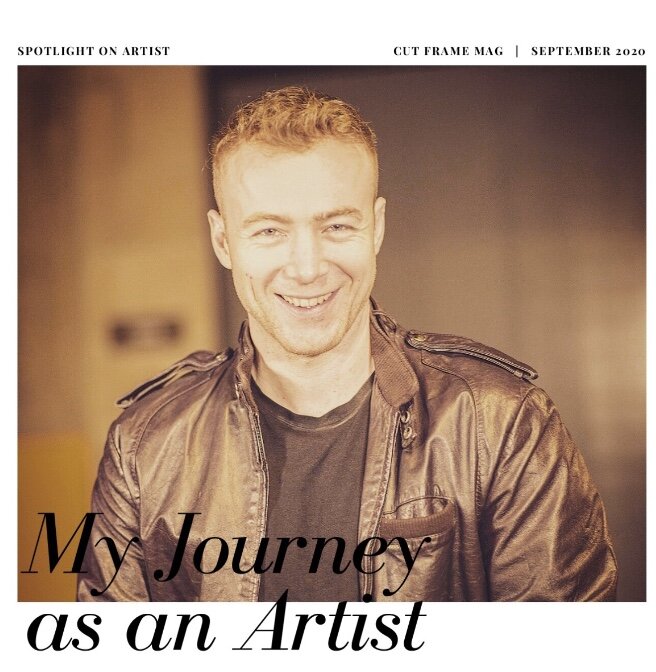

I had the pleasure of interviewing Laurence Fuller. He is best known for his lead roles in independent films Road To The Well, Apostle Peter & The Last Supper, Paint It Red and Echoes Of You, but he got his start in British theatre, training at Bristol Old Vic and taking the lead role in the West End theatre production of Madness In Valencia. During the lockdown, he has rediscovered his passion for writing with a screenplay about his father MODERN ART, which so far this year has won awards and placed as a Finalist in 15 of the screenwriting competitions so far this year.

Thank you so much for doing this with us! Can you tell us the story of how you grew up?

Ispent my first years of life in Bath England, the large Robert Natkin painting which hung above our living room called “The Acrobat” signified all that had come before me. The smell of wet plaster wafted throughout the house, emanating from my mother’s studio. She was a sculptor and if she wasn’t casting one of her loved ones in bronze she was creating still lives from fruit and wine bottles. The sound of a tapping typewriter came from my father’s study as he wrote edgy art criticism. Between tadpoles in the pond outside and the snails crawling up the lawn in welcomes yet fleeting sunshine of an English summer, it was ideal.

I was four when my father passed. What hardships then transpired, were counterbalanced by what it conversely instilled in me, a respect for the preciousness of life, and a knowledge of how fleeting it is. It made me more determined to do something with the time I had.

My family moved to Australia when I was Seven, I took to the theatre mostly. Plays by Brecht, Mother Courage, Threepenny Opera, and Shakespeare, Caliban in The Tempest.

Films were like a secret desire, I wanted to make movies about the characters around me, I wanted to portray them, live out great adventures. As I grew up it became not only about adventure but the complexities of the human drama, Scorsese films were my favorite. It was a secret obsession. My stepfather was stringently averse to the encroachment of American Modernism, but I found this to be limiting. What about the great American films? What about the exceptions? What about the cinematic masterpieces?

Can you share a story with us about what brought you to this specific career path?

As I started doing more Shakespeare in small theatre productions in Canberra I remember a few performances really stuck out to me.

John Bell from Bell Shakespeare doing Richard III, he is really Australia’s Laurence Olivier and brought Shakespeare to our generation of young Australians. An incredibly dynamic performer. I don’t know if he has done letter performances then that perhaps he has, but to me it’s so far the best I’ve seen anyone on stage. I don’t think I’ve ever been so gripped from beginning to end in any production.

When I applied to drama schools several years later all my peers were choosing monologues from Hamlet, but I chose Richard III. It was something my late tutor at Bristol Old Vic Bonnie Hurren commented on as well, why at 19 was I choosing this crippled, middle-aged, disfigured slithering King and not the young and spritely Prince Harry from Henry IV?

The first day that I met Bonnie I was several hours early for the audition day, I’d lost the letter with the details on it and thought I should go in first thing in the morning just in case, I was waiting in the lobby of the old Victorian building that would be the home for my course that year, she walked down the creek wooden stairs completely in her own world thinking of time passed, relationships never fulfilled, desires misaligned, a fellow course member would later say to me she thought that Bonnie spent a lot of her time crying in private, I never knew why he thought this, there was a shrill exuberance to her and an unshakable grace, that I suppose in reflection masked a deep unrequitedness. In my eyes, she was a strong figure that knew the secrets to it all if only she would reveal them to me. She was a very tall and slender woman her movements were always graceful and completely synced up with the rest of her mind and voice. Not unlike Lesley Manville's portrayal of Cyril in Phantom Thread. Bonnie was used to a very tidy routine when it came to the running of her course, we were there to learn excellence in our craft, nothing else would be tolerated. As she walked down the stairs I interrupted her thoughts with a confident introduction, impelled purely by the same determination which has seen me through to this point. She was startled, yet I could tell happily so, she told me I was too early and that I should go over the road across the park to get some hot chocolate at her favorite cafe, I did and it was delicious.

Though my audition piece to gain acceptance in BOVTS was not as you would have imagined up until this point, To Be Or Not To Be, it was Now Is The Winter Of Our Discontent from the opening monologue of Richard III. A choice which Bonnie later berated me for, but at the time seemed intrigued enough to talk me out of my placement I had received at the Oxford School Of Drama. There was some connection we’d formed that morning which only intensified the following year, and began the seed of a deep Method rebellion within me that has never died.

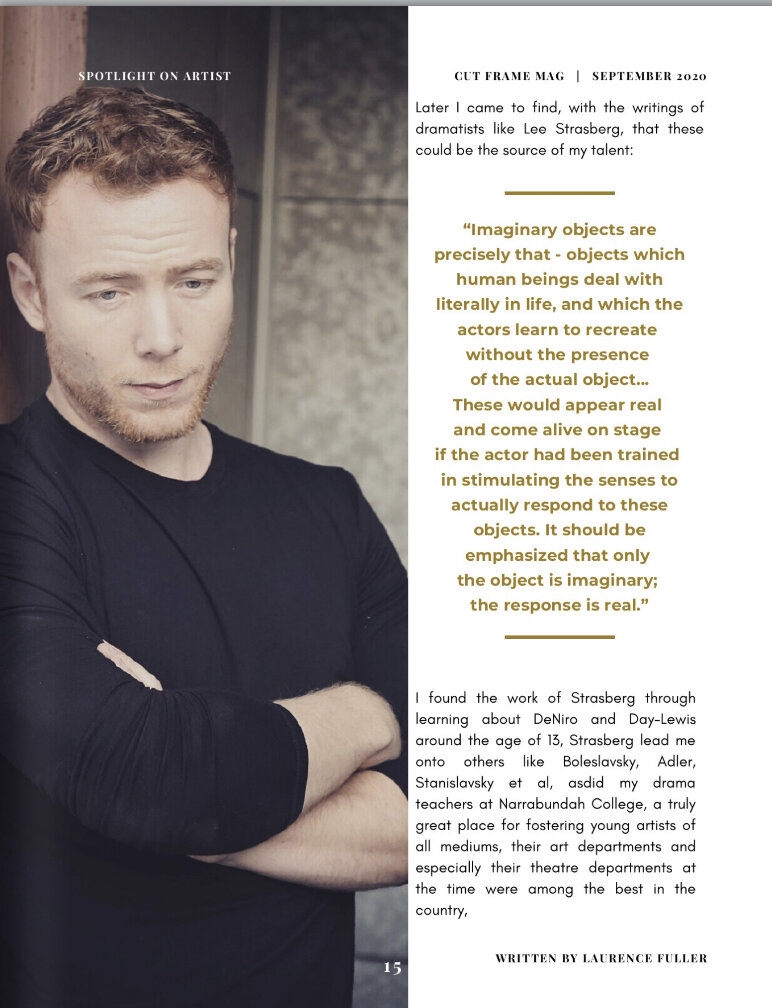

Often during that time I would sit on the steps of the building and imagine what Day-Lewis’ time here must have been like, the teachers often talked about him, about performances he gave which foreshadowed the greatness to come. The intensity he had about everything, he’d often stop by on his motorcycle to visit them. I tried to imagine what he had learned from his time there and how much what we now know him for can be attributed to that learning.

I did the piece again when I got to LA and started training at Ivana Chubbuck Studio at first under Michael Woolson. I brought this rotisserie chicken on stage and started ripping it apart half-naked with bare hands and wiping the chicken breeze on my chest. That was a more experimental take, I just thought Richard is so good at playing up to his monstrous reputation and using it to his advantage, why not go all out. My peers still recount ‘remember the chicken?’

Can you tell us the most interesting story that happened to you since you began your career?

Around 2005 I acquired a painting by Peter Booth, who was one of the top painters in Australia at the time, his dystopian view and epic landscape with this mythic narrative was really powerful. There was one painting, in particular, that was shown to me by the art dealer Rex Irwin “Man With Bandaged Head”, a figure of a man who was without identity, internally and externally covered in bandages. I held onto that painting living through poverty as a young struggling artist, with nothing else to my name. And I made a film about the experience, at the time it was semi-autobiographical, heavily doctored by the writer/director Jim Lounsbury, but the core of the story was there and that painting was at its center. Possession(s) was about a man who gave up everything in his life to own a work of art only to have its physical value as an object destroyed. After the film was made I did end up selling that painting and that raised me enough funds to move to LA and start my journey making films.

Can you share a story about the funniest mistake you made when you were first starting? Can you tell us what lesson you learned from that?

I should preface this story with the common cultural custom in Europe to kiss someone on the cheek when you hug and greet them, it’s sort of an old fashioned, but everyone is used to it. Probably that custom will be put on hold for a while with all that’s going on in the world, but at this time we were pandemic free.

My first manager meeting in LA was with a lady I had been corresponding with via email at one of the top firms in Hollywood. She had heard good things about me, was excited about my play and my auditions tapes. We were excited to meet each other and I’d finally made it across the pond and I could see her in person. I waited in the lobby of this firm, slightly nervous and she came out to greet me with arms stretched out. I immediately offered my hand to shake, but she battered it away and went in for the hug, I suppose as we had been corresponding for so long. This lady happened to be slightly short, and I’m slightly tall so she came up to just below my neck. As a habit and automatic reaction to a hug greeting, I went for a customary cheek kiss, but as her cheek was not exposed and I could only see the top of her head, I kissed the top of her head, and the kissing sound that accompanies the cool and smooth kiss on the cheek greeting was almost twice as loud. This was immediately followed by a silence which felt like forever, as she totally unacquainted with the custom and being very much a Los Angelean, who for the most part are completely uncomfortable with their personal space being invaded, remained awkwardly frozen in the hug, I could almost hear her thoughts ‘did he just kiss the top of my head?’

The meeting from that point on was pretty much a disaster and I didn’t end up signing with that company. Lesson learned; always know the customs of the culture you’re in!

What are some of the most interesting or exciting projects you are working on now?

Obviously productions are up in the air at the moment, but am definitely excited about what I do have coming up:

MODERN ART is a screenplay I’ve been developing for 4 years. I just started submitting the screenplay to competitions this year and already it has won a 3rd place award at a completion for best Screenplay and received Finalist placement in 10 others.

This project has allowed me a dialog with the father I never knew. Until now Peter Fuller was for me, a box of papers at the TATE museum. When I decided to write a screenplay about him, what I discovered amongst those papers has changed my life forever. I’m excited to share with the world, what I have found.

Peter Fuller was like a punch in the guts to the art world from 1969 to 1990, and until his last breath he was radical. His writings spanned art history, psychology, sociology, aesthetics, biology, and religion, all emanating from his primary fascination with the arts. But it was his search for beauty in life and in art which made him so fascinating. The extent to which Peter invested himself in this discovery proved that Modern Art is not only a medium for entertainment and trade, but by engaging with artfully we could come to know ourselves.

His loss was a tragedy not just me but for leaders of the art world, and yet rediscovering him in this way I have perhaps gotten to know him better than I could have living. We need this story now, our world needs healing, its heart is breaking. I know that developing this project has been for me personally a consoling and life-changing experience, my hope is that it will be for others too.

Once you’ve had enough education, make use of it by creating something of your own. There will come a time when putting too much weight on that stuff will hold you back and what you really need to be doing is to put in the hard graft and actually making something to call your own. All actors should write.

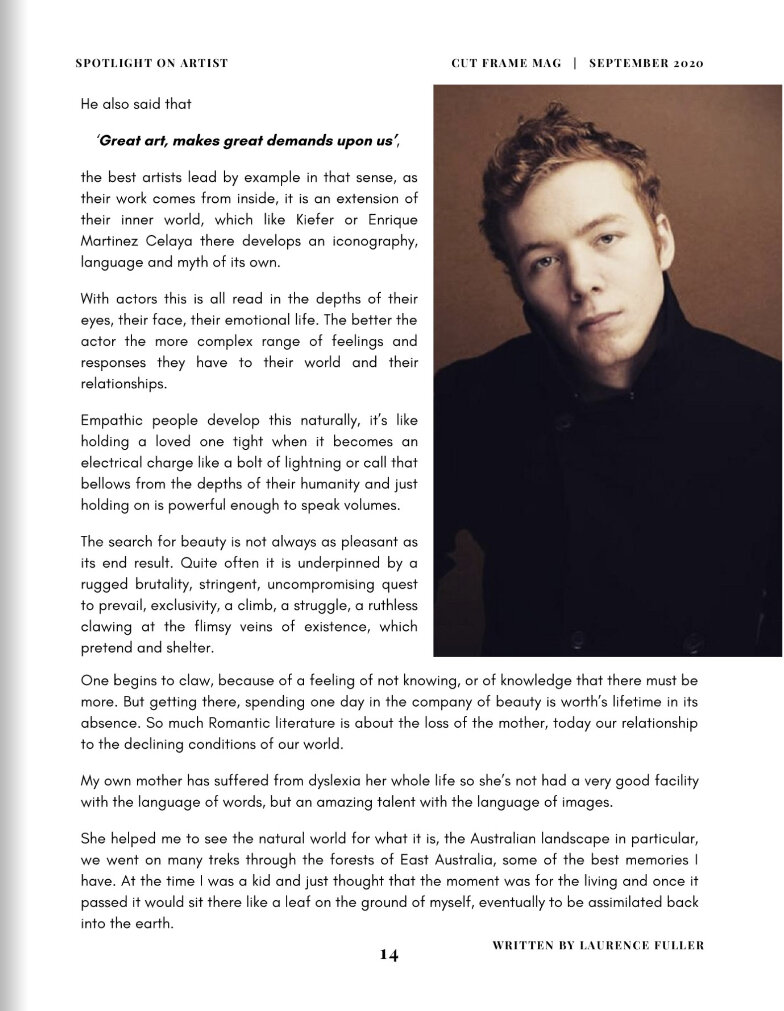

I believe that making art should be akin to an act of love, whether it is love for a muse, the piece, or love for oneself, otherwise it doesn’t make much sense. My father, once talked about painting being like a skin between the internal and external world, he was talking about the work of the American Abstract painter Robert Natkin, but I think that idea translates to all the arts. And like the child has objects, toys, teddy bears which he/she transfers their emotional inner life to create their manifestations of the world they would want to see so too do we grow up as adults spiraling over the same behaviors with greater intensity, focus and realization. He also said that ‘Great art, makes great demands upon us’, the best artists lead by example in that sense, as their work comes from inside, it is an extension of their inner world, which like Kiefer or Enrique Martinez Celaya there develops an iconography, language and myth of its own.

I also did a short recently with director Henry Quilici that has interesting parallels and is currently getting some love on Twitter, it is a really heartfelt short about a classical pianist and a homeless boy that seems to be capturing people’s imagination right now. That can now be seen here and is being passed around the Twitosphere: http://www.laurencefuller.art/echoes-of-you

Five Families is a proof of concept short I acted in for director Adam Cushman, taking the point of view that the police are actually the new gangsters. Which has become increasingly relevant in light of recent events and is now becoming an important story. In that one I had the honor of acting opposite screen legend Barry Primus, who comes from that whole DeNiro, Scorsese crew and just had a great supporting part in the Irishman.

We are very interested in diversity in the entertainment industry. Can you share three reasons with our readers about why you think it’s important to have diversity represented in film and television? How can that potentially affect our culture?

It’s very important to be inclusive of all members of humanity and not to discriminate or be racist towards anyone, for any reason. Discrimination, unfortunately, happens a lot in our industry to everyone for different reasons, and that is sad. I believe in meritocracy if you have the passion, the talent, the skill to be the best person for the job, then you should get that job. If your film is the best film, it should be programmed in the festival. It is sad that it’s not necessarily that way. If you grow up with the goal of becoming the greatest piano player, the top lawyer, or doctor, there is a clear path to getting there and more often than not you will be judged on your ability. If your goal is to be the best actor, writer, or filmmaker, you quickly find how political it all is. It’s unfortunate and it also becomes a daily struggle to navigate. Privilege comes in many forms, but it's a positive step that if you are diverse there are now many funds, programs, and scholarships that have been set up since I started in the industry but in the last five years especially.

What are your “5 things I wish someone told me when I first started” and why. Please share a story or example for each.

1.) When you’re starting out you’re really trying to figure out who you are and what you have to offer, this is actually the most important thing you can do. Drama Schools can only be there to facilitate that and never any more, they can’t give it to you. I remember searching for my artistic identity in my teachers in vain. Like nurses can only be there to facilitate your creative birth, but you have to ultimately be the one to do it and follow through.

I remember going into Bristol Old Vic thinking it would provide me with the secrets to unlocking my soul. Of course the teachers already know that this can only be done from within you. I remember the head tutor of my course at Bristol Old Vic, Bonnie Hurren saying I should read David Mamet’s True & False specifically because it serves as an ideological deconstruction of the institutional art. It inevitably goes too far and it’s hunting of ideology can only can to false conclusions. After I finished the book I went back to Bonnie and asked if I no longer needed to be at the school anymore because I’d read it.

Theory can never surpass the universal values of learning, mastery. Learn from the best, there are many practitioners doing admirable work out there who are capable leaders and dramaturgists. But it’s important to never just get lost in one person’s ideas. Each person should find out for themselves what they believe in, not merely as a polemical response either because there isn’t much use in dwelling on what you dislike or what you do not identify with, this usually just leads to a cankering of the creative force, the libido, the will and doesn’t go anywhere. Find out who you are and what you love, be that and foster that. The lesson for me was: beware of false prophets.

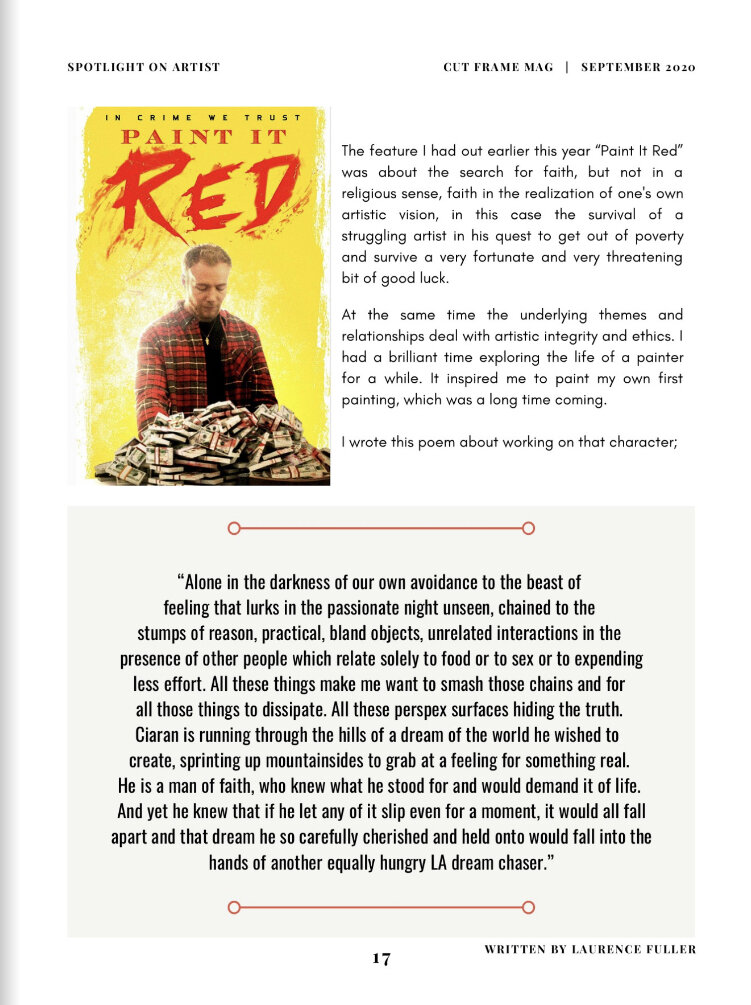

2.) The feature I had out earlier this year “Paint It Red” was about the search for faith, but not in a religious sense, faith in the realization of one’s own artistic vision, in this case, the survival of a struggling artist in his quest to get out of poverty and survive a very fortunate and very threatening bit of good luck. At the same time, the underlying themes and relationships deal with artistic integrity and ethics. I had a brilliant time exploring the life of a painter for a while. It inspired me to paint my own first painting, which was a long time coming.

I wrote this poem about working on that character; “Alone in the darkness of our own avoidance to the beast of feeling that lurks in the passionate night unseen, chained to the stumps of reason, practical, bland objects, unrelated interactions in the presence of other people which relate solely to food or to sex or to expending less effort. All these things make me want to smash those chains and for all those things to dissipate. All these perspex surfaces hiding the truth. Ciaran is running through the hills of a dream of the world he wished to create, sprinting up mountainsides to grab at a feeling for something real. He is a man of faith, who knew what he stood for and would demand it of life. And yet he knew that if he let any of it slip even for a moment, it would all fall apart and that dream he so carefully cherished and held onto would fall into the hands of another equally hungry LA dream chaser.”

3.) I remember punching the floor with excitement when my agent called me telling me I’d booked the role.

The first draft that I read when they called me in to audition was initially a full 90 minutes of the Last Supper of Jesus Christ. The casting director Billy Damota initially brought me in for a much smaller role, it was one of the apostles that I think was actually cut from the final draft, the piece was a monolog, a moral dilemma. Jesus had just told his 12 disciples that one of them was about to betray him, of course, we know in hindsight it was Judas, but the narrative explores what was going on in the minds of the apostles in that moment, their doubts and insecurities, as they wrestled with their humanity. I remember the final line was “is it me lord?” as in, is it me that betrays you? As I was walking out the audition the casting associate Dea Vise stopped me and said ‘wait Laurence, there’s another role they wanted you to read for’, she then handed me a 20 pages script titled The Fisherman about a Roman soldier talking to an older apostle as he is progressively converted to Christianity. They gave me an hour to read over the script, then they brought me back in to read for the director Gabe Sabloff who was the mastermind behind all this. A week later I got a call from my agent saying ‘you’ve got the part’, it was one of the most exciting moments of my life.

The casting director, Dea Vise tells the story like this; “Laurence Fuller was reading to play a Roman guard. He had a few lines and was basically just in a few scenes as the story was originally about Peter at the Last Supper with Jesus and the Apostles. Well, Laurence came in the room, read his few lines so thoughtfully and with such brilliance that he got the job to play the guard watching over Apostle Peter (played by Robert Loggia) while he was in prison. As a matter of fact, Laurence was SO GOOD that they rewrote the movie to be about the relationship between the guard and Peter. So, the names above the title in the movie are now Robert Loggia and Laurence Fuller and, of course, Jesus was played by Bruce Marciano. Three names above the title and one of them started out with a few lines. Be that good. Be that interesting to watch! Break a leg out there!”

4.) The film ECHOES OF YOU is about a classical pianist who finds fulfillment in an unlikely place. As he’s auditioning and falling short of becoming a concert pianist he meets a young homeless boy and teaches him how to play a song he wrote for his father. This all comes back around in a really surprising, karmic and spiritual experience.

The director Henry Quilici really nailed that concept of the spiritual in art, and how the arts can be a compassionate, humanitarian thing. We treat it as a gift to someone else. And do I think I found it? Yeah. The experience of making this short was very emotional. It was an emotional part, and so it did require me to go into some vulnerable places within myself.

I remember first reading the script and bursting into tears when I came to the end. That message of faith in the capacity for even the smallest of moments can be reimagined through the artist’s lens to something illuminating and beautiful.

I think it’s rare to find that sort of message in the modern world, there’s a lot out there that’s just attention-grabbing nonsense. It also depends on the person receiving the thing, to one person a flower could bring them to tears in pure exaltation at the complexities of existence, to another, it might be nothing but a wet twig. It depends on the capacity for sensitivity and sensual faculties of the individual. As an artist that is the aspect that’s pointless to even try and control, any attempts to do so will leave the work itself feeling inauthentic. For those reasons I really have become immune to what the reception to my work is a lot of the time. To make anything of worth you have to have that sort of conviction in your own ability to create what you know to be good work and to do what you want to do. The artist Anselm Kiefer said that each work of art cancels out those that precede it. He was talking about the language of history as a contribution to culture.

I knew for this piece specifically if it was structured for the effect of a beautiful karmic experience, that was designed to inspire compassion. That in itself is very difficult to accomplish, so it had to be real love, really beautiful and powerfully compassionate. It had to be the biggest moment in this man’s life. Bigger than winning an Oscar. Like being rekindled with the love of one’s life, seeing their child or anyone they have loved and felt really deserved it, become a success in the world. I knew I had to open up and be vulnerable in front of the camera, which is impossible to fake, the camera sees everything, it took digging deep and talking to the ghosts of my past.

That’s the only way to get through to people with this sort of message, is to speak the truth from the depths of your humanity and have faith that people will listen, because if it is authentic then, they will, they will. All the lead roles I’ve had so far in “Road To The Well”, “Apostle Peter & The Last Supper” and “Paint It Red” have been about a person losing their faith and then finding it again with stronger conviction in some other form later on, that is much the same with this piece too.

Henry showed me a short documentary he made about discovering his grandfather through a box of letters and journals he found in the attic. We discussed how eerily similar the project which fills my days is, a film about my father, the late art critic Peter Fuller and going through his journals almost every day from the TATE archive. I’ve made my way through a huge chunk of his writings public and private, to piece together who he was. Of course, to understand him I also needed to read through the work of his collaborators and all his influences as well. And now his echoes speak to me, and some things are so special they take more than just one lifetime to complete. That’s really what this piece is about, the Greek philosopher Hippocrates said: “Life is short, but art is long”.

I saw this film as an opportunity to contribute to something beautiful. The biggest thing was finding the internal objects for what the piano meant to me and my journey. The struggle that I’ve been through as an artist, and the people in my life I’ve been doing this for. I saw the ghosts of my ancestors who I imagined knowing, what it would mean to them to see me on that stage, the underlying sense of loss knowing that I will never have that, I will never see their faces in that audience. But to live it out like Stanislavsky would say ‘as if’ for the rest of us living to enjoy.

The accent was one aspect to this performance, I’ve worked with an American accent a lot in LA it’s bread and butter. Speaking in my natural voice out here people say to me ‘you have an accent’, but everyone who speaks a language speaks with an accent and we learned that accent when we were young from the people around us. The same can be done in adulthood if need be.

Andrew is very masculine, and very feminine at the same time. That paradox is something I could identify with. I’m a heterosexual male, but I also feel left out of the discussion when it comes to rigid gender definitions, I feel misrepresented. In my daily practices of writing poetry and Martial Arts, I feel in touch with the extremities of both the masculine and feminine within myself. I wrote a poem about it which took me the better part of a year to finish, thirty pages of prose, representing the extreme forces of male and female within me battling it out for Elysium. In part I was inspired by three female artists in England right now who have depicted The Minotaur, there is this masculine sensual creature that has a physicality, a powerful frame, a capacity to rule as king of paradise and yet by that same token a beautiful emotional complexity as he sits reading through pages of poetry. There’s something amazing and compassionate about that to see the redeemable and positive qualities of this creature's contribution to the world when all else would see him as something frightening to destroy. Regardless of some of the more superficial representations of The Minotaur throughout art history, I feel there’s something a lot more genuine and passionate about these female’s extension of where Picasso left off, the myth of the minotaur. In the paradox of extremities of both the masculine and the feminine and finding love for oneself.

With “Echoes Of You” the first meeting with Henry Quilici happened at the end of last year shooting his USC short “Tweaker Speak” about a meth addict dealing with the demons of addiction as he tried to get his daughter back. A very different piece. I noticed the things Henry would say were very to the point, very clear, uncluttered by doubts or abstract theory, his notes always referred back to the story or to human experience.

A couple months later I was contacted by Henry and his producer Cam Burnett (a young filmmaker with similar sensibilities). When I first read the script and came to the end, I burst into tears, it had come to me soon after I had finished reading a passage by John Berger in his book “A Painter Of Our Time” which detailed the life of an artist, most often one of constant sacrifice for their work. Henry had captured that plight so beautifully with this story, I had to do it.

Henry showed me a short documentary he made about discovering his grandfather through a box of letters and journals he found in the attic. We discussed how eerily similar the project which fills my days is, a film about my father, the late art critic Peter Fuller and going through his journals almost every day from the TATE archive. I’ve made my way through a huge chunk of his writings public and private, to piece together a singular man of principles in his writings. And now his echoes speak to me. Some things are so special they take more than just one lifetime to complete. That’s really what this piece is about, the Greek philosopher Hippocrates said “Life is short, but art is long”.

I found Henry to be incredibly clear about what he wanted, everything very specific in emotional terms, he spoke very subjectively and compassionately, not the sort of move your head a little to the left which can leave actors feeling like meat puppets and end up with mechanical performances. He worked as many of the best directors do, from the inside out.

In many ways, I feel Echoes Of You is about time. Man and time have such strange relationship, as we exist in time but the way we experience it is never as it actually unfolds. As our internal clock passes with a tether to society's expectations of us, we too little consider the effect our actions are having on the people around us. The echoes of not just our voice in a cave, but our movements in the world each day. To show up each day sit down at the keys, explore the depths of our unconscious.

Echoes have are a vital component in the acting process, because what we end up becoming in performance is an echo of that first reading of the script, and that feeling which bounces off the walls of our unconscious, the ever-expanding and retracting self, is reshaped with every bump. Like throwing clay against a wall, picking it up and throwing it again against another. Time forms a totally new object, with the heart of the original idea, but with time and movement a new object entirely.

The time it takes for something truly special to emerge in our culture can be an arduous one, this is why it is so important for artists to have faith, to have the strength to step back and see a bit further into the future and into the past with all their actions.

For instance, there is the intention to hit a piano key, the thought, the will to create music, the doing of it, the vibrations in wood and in the air which causes the sound and then there is the trace memory the sound makes into us. The next day the vibrations are gone but what is it that remains, what else can we call it but a feeling.

Pushing into these echoes of ourselves man finds again another feeling, another self, rewriting of one's own personal history reveals many selves splintered off into a kaleidoscope of you.

Even the best and brightest fall prey to doubts because of the time it can take from the conception of an idea to its real-life manifestation. And yet there are moments that are eternal for us, moments which last in eternity as long as we last and when we give them to another they last forever in them. Those things we cherish that make the world better for our existing and their creation pushing forward a spiritual progress.

The compassionate passing on to generations is an important part of this story. If we chose to listen, we can take the best of somebody with us on the hardest roads in life that stretch out before us. It can feel like whispers in the wind sometimes when we talk about something that has a deep and powerful resonance to us.

This piece made me think deeply about the effects of what I wish to leave behind. What marks in the sand I wish to make. We’re all scratching up the dirt at the moment, thousands of impressions made, often without thought for their effects.

What matters are not the constant floods of change which define our generation, but the development of the spirit, the inner world which we must cherish and rely on to provide us with hope.

In the week before shooting, I read Viktor E Frenkel’s “Man’s Search For Meaning” in which he suggests the survivors of the concentration camps during WWII of which he himself was a survivor, had something to live for, that they could cherish on the inside. That they had been touched by great works of art, literature, theatre and music and these moments in their life were the memories which got them through.

Confronted with a boy who is living through possibly the worst conditions a child could be subjected to in our society, I think Andrew gave him all that he had, and aside from the odd sandwich and a place to crash, what he had to give was music, the stronger Andrew could instill this dream of music, the better chance that echoes had of speaking through all the overwhelming obstacles this boy had to encounter.

Photographer - Stev Elam

Henry’s brother Max Quilici wrote the main theme to Echoes. The piece was so minimally and yet effectively done, I felt there was no way I could do this part without learning at least some of the piano in order to play this song. With the couple weeks of preparation, never having laid hands on a piano before, I managed to learn how to play the first half of the song.

I came across a documentary preparing for the role called Pianomania, about a piano tuner for some of the world’s best pianists. He was someone whose love for the piano extends beyond the performance, becomes almost an intellectual pursuit, like preparing for a role that one never acts. The language that he began to use to describe moments within a sound was complex, abstract and beautiful. The joy and the passion for the music then became a dedication to the development of someone else’s craft.

That has always been something that’s interested me, how much should we use art of the same medium to influence our work. I feel that art should be the language to express the fullness of life. But the conflict then comes when confronted with another’s work that we stand in admiration, that admiration must then come from an ideal within us that we wish to reach. Then the choice becomes whether to run forward towards that same goal, almost like an Oedipus trying to surpass the father, or whether to stand back and remain in a place of fixed and constant admiration allowing it to either influence one’s work in another medium, or is it enough to touch a place within a performance, to shape the artists work by pushing a sound, an aesthetic a feeling further than they could have by themselves. The position of a conductor to a musician, a director to an actor, or a parent to a child, shaping the raw materials of a human being in a particular direction, for the purpose of benefiting humanity.

5.) Brace yourself, because you’re going to need to have a lot of patience, as well as determination and persistence, bear in mind, people are reading into everything you put out there so approach your professional relationships with confidence and love and with the intention to help communities of people make art.

Make peace with yourself, deep down find an inner resolve that is self-rewarding. Don’t expect much from others, just be thankful to be there and to have the opportunity to do what you love. It’s a job and it’s also a gift that you’re giving, even in the strangest of characters, you’re reflecting a part of humanity back at itself. Stay away from high conflict people in your personal life as much as possible. That can be quite a challenge, especially in LA for some reason, people who feed off drama are dangerous to your precious faculties as an artist and can drain you, look instead to the people who show you love and encouragement, know that’s happening for a reason and seek more of that. I’ve seen people shoot themselves in the foot enough times to know that attitude is a huge factor. Even talking to agents can be really insightful when they have to deal with a client who's just bitching at them instead of being grateful for the positive things they’ve done. Just like you want to avoid high conflict people, don’t be one!

Focus on what you are and what you want to become, notice the people who are helping you become that and walk away from the people who are not.

I personally do a lot of reflecting and learning from mistakes, by doing so I feel I have a very attuned gauge to fairness, if someone consistently does not take accountability it’s a sign to limit exposure as much a possible.

Obviously there’s a lot of advice already out there about cracking into the business etc, so that should be easy enough to google. My input about that is to spend time on your business, on your social media, unfortunately, that is important now. But curate your social media, for what you put out and what you take in, protect your cognition and your internal objects. Too much flicking around the unimportant stuff will dull the senses. I do think there is a higher use of social media in a sense. If you can train yourself to use it sparingly but to use it to seek out things that you like and the people in your communities that are regularly engaging with those same things. Theatre and independent films are great places to start. I love going to the film festivals that my films get into and then meeting the other filmmakers and actors there, talking to them and going to their screenings. The ones in California I love are Dances With Films, Newport Beach Film Festival and San Diego Film Festival, a few others too, then you have all the majors everybody knows about Sundance et al.

And while you’re looking to get cast in your next project in between auditions I would personally advise writing everyday.

When Adam Cushman approached me to play Seymour in “Five Families”, we discussed how there was something Romantic about Seymour’s longing for the past, he told me to read Shelley, that sort of emotional intensity was something I wanted to capture for this character. I’d met Adam on his last feature “The Maestro” which turned out to be a hit at the film festivals, I was cast in that to play the young John Williams by producer David J Philips, and I met David at the premiere of “Road To The Well” at Dances With Films Festival in Hollywood not long before that.

Barry Primus was playing my Grandfather, we rehearsed on location which turned out to be Barry’s house. As he showed us around we walked past a poster of the film he directed and DeNiro was peering out, Barry had directed him in the film “Mistresses”, I looked around and there were family pictures with one of the people who I was reading about in books back in my early discoveries of cinema, whose performances had inspired me to go on this journey in the first place. And a few weeks later I was sat opposite Barry peering into his eyes as he was playing my grandfather locked in a power struggle with the young Oedipus that was my character. It felt like I was apart of that legacy in some way.

I couldn’t have predicted something like that would happen and I would be there on that day. I just knew when I met the director Adam Cushman there was something special about this artist and I wanted to be apart of his journey. Like Day-Lewis, I had been inspired by DeNiro’s capacity to push the boundaries of film acting and to take what I’d learned from the British theatre to the American screen. I wrote this one about the experience;

“Adam Cushman helped me find my darkness with this piece, it was rooted in a longing for the past in adolescence and lost love, a time when people followed their desire without consideration for every consequence, but to challenge the status quo with action.

The last of a dying breed of gangster, nostalgic and Romantic for another time when passions followed glory and the challenges of the will, were met with the force of present days. Today I am a better man, today I feel that carnal longing, tomorrow is destroyed by the turning of coming authority. They pressure me to give up my sword, but I shall die by valiance and go down in history as the first forever gangster glory.

Six shooters shuddering in the pockets of my armed forces, there I am wishing for you to change your ways to musty running hallways of life and lofty dreams.

Protect your family, know who they are, know that legacy will be written on your tombstone carved in marble, heroes are carved in marble and the weak go silently by.

Shelley’s letters of time in a course of crossroads between God and invention told the story a man and monster, broken by his own innate creation.”

By a twist of fate “Five Families” just had its premiere at the same festival I met David three years before, Dances With Films. Networking is a karmic experience, it’s more like a spiritual journey than anything else, we’re all little beacons transmitting our message out to others in the darkness of consciousness, follow the light.

Some people can read the entirety of a poet like William Blake and all they’ll choose to focus on is the word ‘bottom’, or some other salacious misrepresentation of the author, whereas someone else will read the exact same piece of work and walk away transformed and reignited by all the passions a Romantic poet has to offer. Not that Blake’s poems are for the innocent, some are but not all, neither are Charles Baudelaire’s “Flowers Of Evil”, nor Lord Byron’s body of work, almost none of the truly great works of art are wholly pure, and why should they be? They do not cross anyone else’s boundaries but are self-accepting of both humanity's chaos and its light, its masculine and its feminine, the paradox within. The greatest works of art of all mediums are undeniable, unrepressed.

In this sense, I try to have a higher consciousness about what you see in other people. Entertainers, filmmakers, writers, performers of all kinds are not just characters in your own personal fantasies, they’re real people with all sorts of longings, fears, desires, pains and joys. It’s not just about who you know, not who knows you, but what you see in someone else and how you choose to relate to others. I worked with Jane Berliner (talent manager at Authentic) for a number of years and she talked about having integrity in business, and I watched how she had a well-tuned sense of fairness with how she went about things, positive and negative, and I respected that and tried to learn as much as I could from her as an arts entrepreneur. I suppose my career advice is about that, have integrity in your professional relationships, and see yourself as a budding arts entrepreneur, trust that the rest will follow.

For instance, who knows where “Five Families” will go, who will get to see it and what will happen next.

Which tips would you recommend to your colleagues in your industry to help them to thrive and not “burn out”?

I think one should just focus on the personal journey, I wouldn’t even know how to begin trying to be a rival to other actors, unless it was part of a scene, what would be the point?

It has to be a personal, spiritual journey, that is really about trying to find out who you are and investing your passions. If film has fed your soul like it has mine. By filmmakers like Terrence Malick, Stanley Kubrick, Christopher Nolan, PT Andersson, Lars Von Trier, Barry Jenkins, Nicholas Winding Refn,