Night Movements 1897/1990 by Anthony Caro

In light of major Caro retrospective currently on at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, I decided to take a look at the fascinating Saga which unfolded between the sculptor and my father, the art critic Peter Fuller, which lasted throughout both their careers and found itself at the core of the cultural debates of the twentieth century, shedding light on where we find ourselves today. Below is the first article I'd like to post on the subject, this will be followed by a number of interviews and correspondences in the final weeks of the Caro retrospective.

Nothing got my father's Romanticism fired up like the success of a British modernist sculptor. I can't say that I fully get behind the position he takes, but through it we see clearly both sides of the argument. Modernism wouldn't be relevant without the past to fight against, the past would not be cherished without Modernism stepping all over its beautiful face.

In discussing Caro, Peter's argument would seem strangely aggressive without discussing his antithesis; Moore, and through this we can see the relevance of Moore to us as species beings today. Caro, as is Ron Robertson Swann along with the Australian welders who he influenced. However, what may be of more relevance is what comes next?

Inner Sanctum, Ron Robertson Swann 2011

When I was a child in Sydney watching the adults around me go about their business, creating and discussing art, this practice was incredibly popular and supported by the art schools, commercial galleries and government bodies. I remember at the age of 10 dancing on the rubble outside of Ron Robertson Swann's studio, that he would no doubt later turn into something as strong and cerebrally masculine as Inner Sanctum.

This essay serves as a metaphor for the opposing approaches that were still at the forefront of the discussions throughout the 90s. It's hard to say which one 'won' in the end, or if their can be a 'winner', in artistic polemics, it can be easy to forget that all artists are on the same side fighting against philistinism.

Traditional sculpture was criticized as being reactionary and the Modern aesthetic which was once considered revolutionary is now an institution. Today with such a vast sea of disposable art and media out there, once people become tired of the onslaught of the senses, they step back and cherish what they once took for granted in a new light.

The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green

What was once esoteric, is now blasted out to millions of screens in a mass of images just like Ways Of Seeing predicted, and John Berger's question is now posed to us, "who will use these images and for what purpose?". My father was not the only one disappointed by what the avant-garde was to expel as a result of revolutionary values when he wrote Seeing Berger and Aesthetics After Modernism, predicting a loss of what made sculpture and painting great in the first place. But what now? Both traditional values and the Modern Revolution are popular and we get the point already, is it art? Kind of!

In fairness to tradition, the reproduction was unable to do service to a sculpture by Moore in nature and this was the ultimate message behind his posthumously published book Henry Moore: An Interpretation. And in fairness to the traditional sculptural language which Peter talks about and metal welding is opposing, the directness of Caro's Modernist aesthetic has become institutional at this point. Who will have the courage to stand on their own and see the benefits of both?

My generation takes inspiration from everywhere, this leads to a kind of critical sleepiness which is often commented upon within the art world and oh how easy it is to drift to the subject of price as a convenient explanation for its significance. I remember falling prey to the mistake when I was a young collector with eclectic tastes in my teens. But the point is, how does it benefit and speak to you, when it hangs on your wall or is installed in the back yard? What is the praxis of the artist's vision to you personally with its daily consumption through the senses to the subconscious mind.

"Good art is instructive, bad art disseminated not so, therefore the more your see of it the worse for you" - Peter Fuller, Aesthetics After Modernism

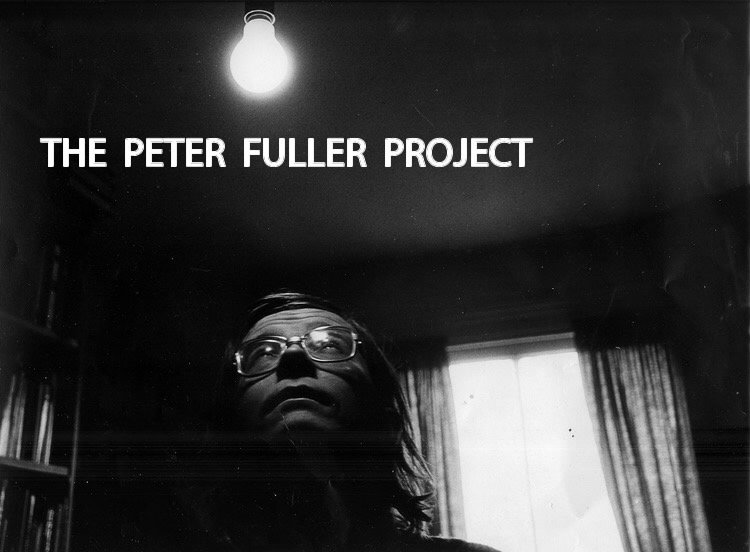

This is regarding how to use art for personal enrichment and how to create art which expresses a heightened consciousness in whatever form that may take. The best art, takes into consideration the language of preceding centuries but in the landscape of our world today and looking into the horizon of cultural activity. This is the underlying truth which is the most relevant aspect of my father's writing today. Yes he was a brilliant polemicist, which makes him the perfect subject for a film - The Peter Fuller Project

But his relevance to the landscape of art criticism and anyone undertaking a study of his work today, has to do with hope for cultural engagement to enrich man, and the potential for some art to echo through the ages, reaching us beyond a historical perspective. This makes art a spiritual force. Peter attempted to fuse all the elements that made up human life to a philosophy which spoke beyond the time that he was writing, yet could be applied with equal validity to the Venus de Milo as to Caro. As a 28 year old in a totally different time and place (an actor in Los Angeles in the post-cyber-revolution), his writings speak to me just as powerfully, as I sit at cafes in Los Feliz between auditions.

The next great artistic movement needs to be forged, not out of any ashes, but as I see it; on the pillars of our heritage in communion with new technology and the coming cybernetic age. A true artist speaks about their deeper selves through the language of their medium. Conventions serve as a means of communication, but the point of art should not be to talk about other art. It should be a means to expression of the self, the soul and the passage of time. Who will cross the boarders of convention into the murky waters of themselves to pull out a radical act of sentience, revealing their consciousness in a uniting statement?

Luke Cook may have been on the right path with MetaModernism and the emotionally brilliant antics of Shia Leboeuf, but this is a discussion for another day, back to sculpture;

Anthony Caro

by Peter Fuller

Wandering, Anthony Caro

'Anthony Caro,' writes Timothy Hilton, opening a review of Diane Waldman's monograph, 'is the most distinguished living British artist... By common consent, he is a master. The artistic justice of his innovation is unquestioned.' Judging by the bland orthodoxy of her text, Diane Waldman would agree. But the review, like the book itself, is typical of that tendentious dishonesty in which Caro's art institutional friends have indulged for years.

The promotion of Caro has always involved an implicit, if not explicit, demotion of Henry Moore, but beside Moore, Caro remains a mere upstart in sculpture. Moreover, I believe that far from being a 'master', Caro was a Judas among sculptors, the betrayer of the tradition he inherited. Indeed, though Waldman is careful to give no hint of the fact, 'the artistic justice' of Caro's innovations has never been more vigorously questioned than today. The facts about what Caro did have been repeatedly chronicled and are not seriously disputed. Caro studied engineering at Cambridge, and later learned the rudiments of sculpture under Charles Wheeler, a Royal Academician; between 1951 and 1953, he was an assistant to Henry Moore. For much of the 1950s, he was an Expressionist sculptor of moderate ability - just how moderate can be seen in such works as Woman Waking Up, now in the Arts Council collection. But, in 1959 Caro met Clement Greenberg, an influential critic of American Abstract painting. Thenceforth, by his own confession, everything changed.

That same year, Caro went to America where he met up with 'Post-Painterly' Abstract painters like Kenneth Noland and Jules Olitski. He also became acquainted, for the first time, with David Smith's sculpture. When he came back from America, Caro demonstrated in Twenty-Four Hours, of 1960, that he had found a new set of stylistic clothes. This piece consisted of three flat steel planes set up in a relentlessly frontal arrangement. One of them, the circle, carried a specific reference to Noland's 'Target' paintings.

Caro demonstrated that he was determined to jettison the imaginative, or image-making, component of sculpture altogether. He went 'radically abstract' and eschewed all reference to anthropomorphic or natural form. He gave up drawing and traditional sculptural techniques, like carving and modelling, in favour of the placement of preconstituted, industrial elements (like I-beams, tank-tops, and sheet steel), which others joined together for him by welds. His work ceased to show any of the sculptor's concern with mass, volume, the illusion of internal structure, or the qualities of his materials. Frequently, his wife covered the steel elements with coats of brilliant household paint, so the metal appeared as weightless as plastic or fibreglass. He abandoned the plinth or pedestal, and engaged in a kind of three-dimensional drawing with lines and planes in space. The objects he produced bore precious little resemblance to anything which had previously been recognised as sculpture.

Anthony Caro, Palanquin 1987-91 (photo by Jonty Wilde)

Perhaps because Greenberg had been so intimately involved in his 'conversion', Caro soon attracted the attentions of American academic and institutional Formalist critics. Greenberg had declared, 'He is the only new sculptor whose sustained quality can bear comparison with Smith's.' Michael Fried rubber-stamped this estimate in numerous catalogues and articles. Later, a book- length study by Richard Whelan appeared, to be followed soon after by William Rubin's monograph, issued at the time of the Museum of Modem Art's Caro retrospective in 1975. In 1982 came Diane Waldman's full-scale volume, lavishly illustrated with 300 plates. In addition, Caro's German dealer had recently issued a four-volume catalogue raisonne of his work, edited by Dieter Blume. Never before has so slight a sculptural achievement been so prodigiously documented.

Even in terms of existing Caro studies, Waldman's text is a shallow piece of work. It is hard to identify any facts or arguments in it which have not already been expressed in print elsewhere. The author has nothing new to say about how Caro's work developed from one piece to the next, even though this is the only subject she has anything to tell us about. Her descriptions of the sculptures themselves often read as if they had been taken from a Meccano instruction manual. Even when she strikes an evaluative note she remains unconvincing.

She writes of Orangerie, which is probably one of Caro's best pieces: 'This is a rare work indeed, in which perfectly conceived and executed parts are crystallized to form a breathtaking and culminating visual statement.' One feels, however, that her breath has not been taken. There is no indication that she has ever been moved by the work she is discussing. She writes as if she knows it is her duty to present the goods in this way. Her language has the tone of the motor-manufacturer's brochure, or the estate agent's hand-out. This does not incline one to accept her value judgements.

Anthony Caro, Table Piece Y-98 'Dejeuner sur l'herbe II 1989, (John Riddy)

But very little that has ever been written about Caro has the ring of authentic criticism. With the exception of Greenberg, Caro's American protagonists all appear to assume that the aesthetic value of his work can somehow be equated with his novel devices. For example, Waldman constantly refers to what she calls Caro's 'advanced' style, whereas she criticises Charles Wheeler, Caro's academic teacher, for his 'reactionary forms'. Nonetheless, it remains a moot point who is actually the better sculptor.

The central question, which none of Caro's Formalist critics ever address, is 'What, in terms of sculpture, was the value of Caro's innovations?' It is no use saying, as Hilton does, that their 'artistic justice' is 'unquestioned'. It isn't. There are those, myself included, who believe that good sculpture depends upon the conservation of certain basic modes and practices. Caro violated the fundamental limits of this art form - with disastrous effects on his work, and that of his followers. Nor am I alone in this view. Henry Moore certainly had his erstwhile assistant in mind when, in the early 1960s, he pointed out that 'a second-rater can't turn himself into a first-rater by changing his medium or his style'. The following year, Moore warned against 'change that's made for change's sake'.

'We're getting to a state in which everything is allowed and everybody is about as good as everybody else,' Moore said. 'When anything and everything is allowed both artists and public are going to get bored.' He added, 'Someone will have to take up the challenge of what has been done before. You've got to be ready to break the rules but not to throw them all over unthinkingly.' At this time, Moore repeatedly stressed that 'sculpture is based on and remains close to the human figure'. Work which just consisted of the arrangement of 'pleasant shapes and colours in a pleasing combination' (like Caro's) was just 'too easy'. Moore affirmed the 'full spatial richness' of true sculpture, and its rootedness in a 'humanist-organicist' dimension which could be opposed to the 'false and impermanent' values of a 'synthetic culture'.

Why, then, if Caro's innovations were bereft of any enduring sculptural or aesthetic qualities, did they attract so much attention, and exert such an influence? At the simplest level, they appealed to art world cognoscenti as literary and ideological exercises, or entertaining three-dimensional illustrations of what were once highly fashionable art-critical theories. Beyond that, however, the interest in Caro has always seemed to me (as it appears to have done for Moore) to have had a lot to do with the way in which his works simply mirror the 'false and impermanent' values of that 'synthetic culture'.

Elsewhere, I have tried to show how all manner of cultural factors led to the overestimation of Caro's achievement, from the time of his first one-man show at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1963. It was not just that Late Modernism's quest for stylistic novelty was reaching a peak. There was also a widespread belief in Britain that everything new (and therefore 'good') in art somehow had to originate across the Atlantic. Beyond that, 1963 was a year in which it seemed that some radical cultural transformation was about to take place in Britain. In the Profumo Affair, the old men of British politics were swept off their plinths. Harold Wilson, the Labour leader, spoke with enthusiasm about the 'scientific and technological revolution', and there was much talk of the nationalisation of steel. On all sides, one could feel this cult of newness. In Liverpool, the Beatles made their first appearances. The nation was shaken by the Honest to God affair, when the Bishop of Woolwich caused a national scandal with a popular book about 'Death of God' theology in which he argued against the anthropomorphic conception of the deity, and recommended bringing God down off his pedestal to reconstitute him as 'the ground of being'.

Anthony Caro, Forum 1992-94

Now it has sometimes been said - not least of all by Caro himself - that I criticise him for his lack of 'social' or 'political' content. This is just nonsense. My point is quite the reverse. I believe that his work was much too timely. It is awash with the transient Zeitgeist of the swinging sixties; and, as it lacks any potentially enduring residue of real aesthetic or sculptural quality, I believe that it will, sooner or later, be quietly forgotten, like so much once-fashionable art of the past. Caro's work did not simply fade away as quickly as it had sprouted up, because Caro himself became something of an institution.

Unlike Henry Moore, Caro never commanded much of a following beyond the confines of the art world. Within that world, however, the emperor was widely believed to be wearing resplendent clothes. And Caro was able to reinforce his influence on a generation of younger sculptors through the pedagogic base he established at St Martin's School of Art in Charing Cross Road. What happened at St Martin's remains one of the saddest episodes in the chequered history of British post-second world war art education. Eager and talented sculpture students came to the school from far afield, but the rudiments of true sculpture ceased to be acknowledged there. Drawing, carving, and modelling fell into decline. Students were not encouraged to look at nature, or, for that matter, at Henry's Moore's work. Welding, and steel construction, were taught as if they were the only way forward. There is no doubt that many talented students were effectively destroyed by this 'teaching'. Certainly, no sculptor of merit emerged from the school.

But the dogma spread, and became endemic in many British and American sculpture departments. It was even exported to the Antipodes by Ron Robertson Swann, who had met Caro when they were both assistants to Henry Moore. Swann's imitations of Caro's welded pieces, and those of his various pupils and imitators, now proliferate throughout Australian provincial art museums.

Vault by Ron Robertson Swann,

Caro's work and teaching, however, had effects he did not anticipate. By rejecting the image, mass, and volume, and throwing out carving and modelling, by deserting traditional materials in favour of prefabricated industrial components, and severing the relationship of his work to nature and the human body, Caro had abandoned almost everything that was truly sculptural. And yet he insisted on 'the onward march of art', the need for yet more stylistic reductions. Inevitably, many of his pupils at St Martin's felt encouraged to take things one stage further.

Some, like Barry Flanagan, began to present unworked substances and matter as 'sculpture'; others started to engage in activities like photography, and performance. Predictably, by the mid-1970s, William Tucker, a colleague of Caro's at St Martin's, was complaining that most students were so busy digging holes in the ground, or 'cavorting about in the nude' that it was impossible to get them to make anything at all. But, like Caro, Tucker seemed unaware of the fact that such antics were the inevitable outcome of that tragic reduction and dissolution of the truly sculptural which Caro had initiated. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly apparent to many younger sculptors and critics that there is an anti-aesthetic, anti- sculptural continuity which runs from Caro's Twenty-Four Hours of i960, to the works of his pupils like Gilbert and George, 'The Living Sculptures', who once made a video-tape of themselves getting drunk, which the Tate was foolish enough to acquire.

Although such considerations are not even reflected in Waldman's book, they are certain to have an effect on all future Caro studies. No serious critic will ever again be able simply to assume the sculptural value of what Caro did, since the orthodox, Modernist view of sculpture, which Waldman briefly sketches in the opening pages of her monograph, is becoming untenable. Waldman argues that sculpture could only realise itself by becoming free from representation, 'physicality', monumentality, and any association with architecture. For her, Renaissance sculpture is somehow inherently inadequate because it has not been cut loose from 'the prison of its own physicality'. Modernism emerges as the great redeemer which finally liberates sculpture from the unfortunate constraints under which it has laboured since the beginnings of human history . . . and Modernism achieves its apotheosis in Anthony Caro.

'In shedding his past with such conviction,' Waldman writes, 'Caro was able to make that extraordinary leap into his own time and to free himself to experiment with form as though he were seeing its potential for the first time.'

To me, this seems to misrepresent what sculpture is and what, at its best, it can be. Sculpture no more needs 'liberating' from representation and physicality than poetry needs 'liberating' from rhythm, meaning and language. Nor is it easy to see why the human figure, or indeed 'physicality' itself are things of the past, of no relevance to our time and place. Whatever it gains from its own time, good sculpture is always rooted in certain relatively constant elements of human being and experience which do not change greatly from one moment of history to the next. (This is one reason why the sculpture of the ancient Sumerians and Egyptians remains immediately accessible to us.) By stripping his work of such elements Caro handed it over to the transient ideologies and cultural epiphenomena of our contemporary 'synthetic culture'.

It is perhaps worth asking if, although Caro abandoned sculpture, he did not stumble upon some quite new art, worthwhile in its own right. The litmus test is always the yield of aesthetic pleasure one derives from a given work, and there is no doubt that, at times, some such pleasure is to be derived from a Caro piece. But since, as Waldman herself states, Caro's art is neither 'metaphorical nor descriptive', such pleasure is invariably slight to the point of triviality. It depends, as Moore saw, merely on the pleasing arrangement of certain shapes and colours in space. In this respect, Caro's art does not differ radically from that of a talented window-dresser, or pyrotechnics designer.

Increasingly, however, younger sculptors are turning to what Moore called 'the challenge of what has been done before'. They are rediscovering imagery, the human figure, carving, modelling, and traditional materials - like wood, marble, clay, and stone. These rediscoveries are not merely technical. Caro's forms of construction and collage involved the abandonment of imagination, and the replacement of physical handling by choice and arrangement. (Like the worst Victorian sculptors, Caro does not actually make his own works.) But as Ruskin saw, sculpture proper is an activity in which head, in the form of both intellect and imagination, heart, and hand combine together in transforming work upon materials as given by nature and tradition. Indeed, instead of mimicking the degradation of human work in the industrial era, as so much of Caro's sculpture appears to do, true sculpture affirms creative potentialities which are in grave danger of being lost. This rediscovery of what sculpture can do necessarily involves a rejection of all that has been done in the name of sculpture from Twenty-Four Hours to Gilbert and George.

Large Upright Internal/External Form, Henry Moore, 1981-82 (photo by Jonty Wilde)

In conclusion, I have often pointed out that, whatever Caro's inadequacies as a sculptor, he is certainly more impressive than his legion of followers. In what does this superiority reside? For all his changes of style, Caro has retained a small residue of what he learned - as even Waldman dimly perceives - from Wheeler, and more especially from Moore. Caro is not as completely abstract as some of his commentators make out. As Michael Fried once admitted, Caro's works do not function through an 'internal syntax' of forms alone; rather, something about them continues to be expressive of certain experiences of being in the body. The followers, the sculptural Stalinists (or 'men of steel') who applied the dogmas so relentlessly in Stockwell and elsewhere, failed to recognise this fact. They assumed that it was the stylistic innovations which were the secret of Caro's qualities. But, in the end, even this differential judgement speaks against Caro, because it demonstrates that such sculptural qualities as his work possesses depend upon the residue of traditional, imaginative, figurative and physicalist sculptural concerns within them. Perhaps, if he had not jettisoned so much, he would have been a better sculptor. Or perhaps the change of clothes was necessary to disguise what was, from the beginning, a very slender sculptural talent.

Over the last ten years or so, in Caro's best pieces, he has simply reneged upon one after another of the 'revolutionary' innovations of the early sixties and reintroduced many of sculpture's traditional concerns. This has enraged his disciples, but it has produced some of the most convincing works of his career. Descent From the Cross (After Rembrandt), 1988-9, seems to me a much more compelling sculpture than those thin and dated 'revolutionary' pieces. And yet it involves not only a direct appeal to the high sentiments of European art, but also a sense of mass and volume, and of upright, vertical forms, immediately suggestive of the figure.

Caro's starting point for this assemblage of rusted and waxed steel elements was a painting by Rembrandt in the National Gallery in London. His sculpture depends upon the contrast between the harsh geometry of the cross, with its supporting ladder-like shapes, and the soft, slumping and all-too- vulnerable forms grouped around its base. Nowadays, Caro frequently uses 'soft' forms alluding to flesh and organism. A few years ago, in New York, he even exhibited a number of small, purely figurative sculptures, fashioned in front of the model, but his London dealers did not want him to show them in England. I cannot help wishing that Caro would complete his return to the mainstream of sculpture and fully embrace both image and figure.

1982/89

"Caro in Yorkshire" runs through November 1st at the Yorkshire Sculpture Triangle

Anthony Caro, Promenade 1996

Photos Courtesy of Yorkshire Sculpture Triangle, Perry Green and Stephanie Burns