MODERN ART chronicles a life-long rivalry between two mavericks of the London art world instigated by the rebellious art critic Peter Fuller, as he cuts his path from the swinging sixties through the collapse of modern art in Thatcher-era Britain, escalating to a crescendo that reveals the purpose of beauty and the preciousness of life. This Award Winning screenplay was adapted from Peter’s writings by his son.In September 2020 MODERN ART won Best Adapted Screenplay at Burbank International Film Festival - an incredible honor to have Shane Black one of the most successful screenwriters of all time, present me with this award:

As well as Best Screenplay Award at Bristol Independent Film Festival - 1st Place at Page Turner Screenplay Awards: Adaptation and selected to participate in ScreenCraft Drama, Script Summit, and Scriptation Showcase. These new wins add to our list of 25 competition placements so far this year, with the majority being Finalist or higher. See the full list here: MODERN ART

Today marks the 30 year memorial of Peter’s passing, below is Matthew Colling’s BBC tribute to Peter from 1990.

The Rise Of Modernism

by Peter Fuller

This series of seminars began by pointing to a weakness in the traditional Marxist approach to art, a weakness manifest in the writings of Marx himself, which is immediately raised when we ask the question: How do works of art outlive their origins? I suggested that Sebastiano Timpanaro had pointed to the direction in which we might look for an answer by emphasising the relative biological constancy of ‘the human condition’, a constancy which underlies socio-economic historical variation. I further argued that psychoanalysis, at least psychoanalysis understood as a theory of biological meaning, could thereby be expected to provide a significant component in any materialist aesthetics.

In these last two seminars we will look at what would be another Achilles’ heel of Marxist approaches to works of art, were it possible to have more than one. We will approach the problem of abstraction, or, more generally, why it is that certain types of art which seem to bear no discernible relationship to the perception of the objective world not only appear to us to be ‘good’ but are also capable of giving us intense pleasure.

However 1 am afraid that once again it is going to be necessary to burrow towards tentative answers in a rather labyrinthine way. To hark back to our last session, it may well appear to you at times that I have arrived here with a bag of disjointed fragments. But I would ask you to bear with me. Although it may sometimes seem that we are toying with an extraneous left foot that got attached to the torso of the argument in error, I think, in fact, it does add up.

I would like to begin by referring to a book called, On Not Being Able to Paint, written by Marion Milner, and published in 1950. This book is well-known among educationalists and psychologists, though not, I think, among artists, nor indeed anywhere within the art world. In one sense I suppose that is not surprising: what title could be more seemingly irrelevant to someone who does paint than, On Not Being Able to Paint! In fact, however, Milner’s book is among the most interesting of all texts by practising psychoanalysts on art.

In her introduction, Milner explains how she had spent five years in schools making a scientific study of the way in which children were affected by orthodox educational methods; she found herself subject to growing misgivings about this work and felt that these misgivings were connected with the ‘problem of psychic creativity’. Gradually she came to the view that ‘somehow the problem might be approached through studying one specific area in which I myself had failed to learn something that I wanted to learn.’1 That something, for Milner, was painting:

‘Always, ever since early childhood, I had been interested in learning how to paint. But in spite of having acquired some technical facility in representing the appearance of objects my efforts had always tended to peter out in a maze of uncertainties about what a painter is really trying to do. ’2 The choice of painting as the means towards finding out something about ‘the general educational problem’ was facilitated when Milner discovered that ‘it was possible at times to produce drawings or sketches in an entirely different way from that I had been taught, a way of letting hand and eye do exactly what pleased them without any conscious working to a preconceived intention.’ The book chronicles her attempt to learn to paint largely through the making of drawings in this way. Now I cannot summarise the richness of Milner’s text here, but I do want to focus upon two moments within it. One is what she has to say about her problems with perspective; the other concerns the nature of outline.

Milner explains that at first instead of ‘trying to puzzle out the meaning’ of her free drawings, she carried on ‘trying to study the painter’s task from books’. Up until this point she had assumed that all the painter’s practical problems to do with representing distance, solidity, the grouping of objects, differences of light and shade and so on were matters for common sense, combined with careful study. ‘But,’ she writes, ‘when I tried to begin such careful study there seemed some unknown force interfering.’ It soon became clear to her the difficulty was that ‘the imaginative mind could have strong views of its own on the meanings of light, distance, darkness and so on.’ A particular instance of this was the interference of imagination in perspective drawing. This is how Milner describes it:

‘In spite of having been taught, long ago at school, the rules of perspective, I had recently found that whenever a drawing showed more or less correct perspective, as in drawing a room for instance, the result seemed not worth the effort. But one day I had tried drawing an imaginary room . . . and after a struggle, had managed to avoid showing the furniture in correct perspective. The drawing had been more satisfying than any earlier ones, though I had no notion why. ’3 It then occurred to her that ‘it all depended upon what aspects of objects one was most concerned with’:

‘It was as if one’s mind could want to express the feelings that come from the sense of touch and muscular movement rather than from the sense of sight. In fact it was almost as if one might not want to be concerned, in drawing, with those facts of detachment and separation that are introduced when an observing eye is perched upon a sketching stool, with all the attendant facts of a single-view-point and fixed eye-level and horizontal lines that vanish. It seemed one might want some kind of relation to objects in which one was much more mixed up with them than that.’4

Now at first it seemed to Milner that her ‘unwillingness to face the visual facts of space and distance must be a cowardly attitude, a retreat from the responsibilities of being a separate person.’ But it did not feel to her entirely like a retreat; it felt, she writes, ‘more like a search, a going backwards perhaps, but a going back to look for something, something which could have real value for adult life if only it could be recovered. ’5 Milner had read that ‘painting is concerned with the feelings conveyed by space’, but she realised that before she herself set out to learn to paint she had taken space for granted and never reflected upon what it might mean in terms of feeling:

‘But as soon as I did begin to think about it, it was clear that very intense feelings might be stirred. If one saw it as the primary reality to be manipulated for the satisfaction of all one’s basic needs, beginning with the babyhood problem of reaching for one’s mother’s arms, leading through all the separation from what one loves that the business of living brings, then it was not so surprising that it should be the main preoccupation of the painter ... So it became clear that if painting is concerned with the feelings conveyed by space then it must also be to do with problems of being a separate body in a world of other bodies which occupy different bits of space: in fact it must be deeply concerned with ideas of distance and separation and having and losing.’6 Milner also comments:

‘There were many other aspects of the emotions conveyed by space to be considered. For instance, once you begin to think about distance and separation it is also necessary to think about different ways of being together, or in the jargon of the painting books, composition. ’7 Thus Milner came to see that original work in painting ‘would demand facing certain facts about oneself as a separate being’, facts, she felt, ‘that could often perhaps be successfully bypassed in ordinary living. ’

I now want to turn to what Milner says about outline. It was, she writes, ‘through the study of outline in painting that it became clearer what might be the nature of the spiritual dangers to be faced, if one was to see as the painter sees.’ She then points out that, until she set out on this attempt to learn to paint through free drawings, she ‘had always assumed in some vague way that outlines were “real” ’. In a book about drawing, however, she read that ‘from the visual point of view . . . the boundaries (of masses) are not always clearly defined, but are continually merging into the surrounding mass and losing themselves, to be caught up again later on and defined once more.’8 She then started to look at the objects around her more carefully and found that this was true:

‘When really looked at in relation to each other their outlines were not clear and compact, as I had always supposed them to be, they continually became lost in shadow. Two questions emerged here. First, how was it possible to have remained unaware of this fact for so long? Second, why was such a great mental effort necessary in order to see the edges of objects as they actually show themselves rather than as I had always thought of them?’9 Milner then says that outlines put objects in their place\ this seemed the crux of the matter. ‘For,’ she writes:

‘I noticed that the effort needed in order to see the edges of objects as they really look stirred a dim fear, a fear of what might happen if one let go one’s mental hold on the outline which kept everything separate and in its place.’ Milner then goes on to describe a key experience:

‘After thinking about this I woke one morning and saw two jugs on the table; without any mental struggle I saw the edges in relation to each other, and how gaily they seemed almost to ripple now that they were freed from this grimly practical business of enclosing an object and keeping it in its place. This was surely what painters meant about the play of edges; certainly they did play and I tried a five-minute sketch of the jugs . . . Now also it was easier to understand what painters meant by the phrase “freedom of line’’ because here surely was a reason for its opposite; that is, the emotional need to imprison objects rigidly within themselves. Milner began to perceive that we believe outlines are real (unless we learn to paint) despite the fact that they are, as one ‘Learn to Paint’ book puts it, ‘the one fundamentally unrealistic, non- imitative thing in this whole job of painting’. But because the outline represents the world of fact, of separate, touchable, solid objects, ‘to cling to it was therefore surely to protect oneself against the other world, the world of imagination.’12 Milner thus came to see that insistence upon the reality of outline was associated with:

‘. . . a fear of losing all sense of separating boundaries; particularly the boundaries between the tangible realities of the external world and the imaginative realities of the inner world of feeling and idea; in fact a fear of being mad. ’13 She even ventured the aside:

‘. . . I wondered, if perhaps this was one reason why new experiments in painting can arouse such fierce opposition and anger. People must surely be afraid, without knowing it, that their hold upon reason and sanity is precarious, else they would not so resent being asked to look at visual experience in a new way, they would not be so afraid of not seeing the world as they have always seen it and in the general, publicly agreed way of seeing it.’

Later, we will return to the question of the relationship between insistence upon perspective and outline and history; however, for the moment let us leave Milner with her intriguing problems over objective space and the rippling boundaries of her jugs, at least for the time being, and pick up another of the pieces that I am trying to fit together in this seminar.

This section, as a matter of fact, concerns me intimately: we have reached what seems to have become a regular feature in these seminars, the autobiographical interlude. Now I want to tell you something about the changes, I would say the growth, in—I’ll keep the word for the moment—my ‘taste’ since childhood.

As far as I can remember, I first became interested in paintings when I was seven or eight years old. My father had a great many illustrated art books, and I would take these down from his shelves and look at them. My family also frequently visited art galleries and stately homes but, significantly perhaps,

I think I got more at least at first, from the art books. Initially there was an element of naked sexual investigation about my looking. I saw a lot of different works of art in reproduction, but by and large I was most impressed by those of women without their clothes. At first my art appreciation was accompanied by some guilt feelings; the books belonged to my father and I did not have his permission to gaze upon them. The Oedipal component in this looking is so transparent that it is hardly worth commenting on. Incorporation of visual images is one of the ways in which from infancy to old age we take possession in fantasy of that which we cannot (but wish we could) possess in reality. But despite the primitive character of my interest in art at this time, it would be wrong to suppose that it was entirely without that which someone like Clive Bell might have diagnosed as a rudimentary ‘aesthetic sensibility’.

Let me explain more fully: at first, I did not make much distinction between medical books (of which my father also had a great many) and art books. But soon I was aware of a sense of goodness when I set eyes upon, say, the Rokeby Venus in reproduction, which I did not feel when I looked at, say, Plate V of ‘An Atlas of Gas Poisoning’ contained in a Medical Manual of Chemical Warfare which illustrated, as it so happens, ‘Blistering of the Buttocks by Mustard Gas’. Now this sense of ‘goodness’ could not be explained by reference to the immediate sensuousness of the subject matter alone, which was often similar in those art books and medical manuals which interested me—though in the latter, of course, it tended to be more explicit. Nor, I think, could it be wholly accounted for by saying that art allowed me to indulge my unacceptable ‘instinctual’ voyeuristic impulses in an acceptable way. This could be no more than a part of the truth, if that. Borrowing art books was no less an offence than borrowing medical books. Despite the specificities of the latter I soon came to prefer the former.

This rather vague sense of ‘goodness’ which I derived from certain paintings, even in black-and-white and colour reproductions, had much to do with the development of my ‘taste’. If I was a certain kind of writer about art, I would no doubt claim that this sense of ‘goodness’ and my quest for it represented the awakening of a pure, unsullied, autonomous, ‘aesthetic sensibility’ to ‘Significant Form’, or something of the kind, in the midst of all that crudely sexual researching. But personally, I am inclined to doubt this.

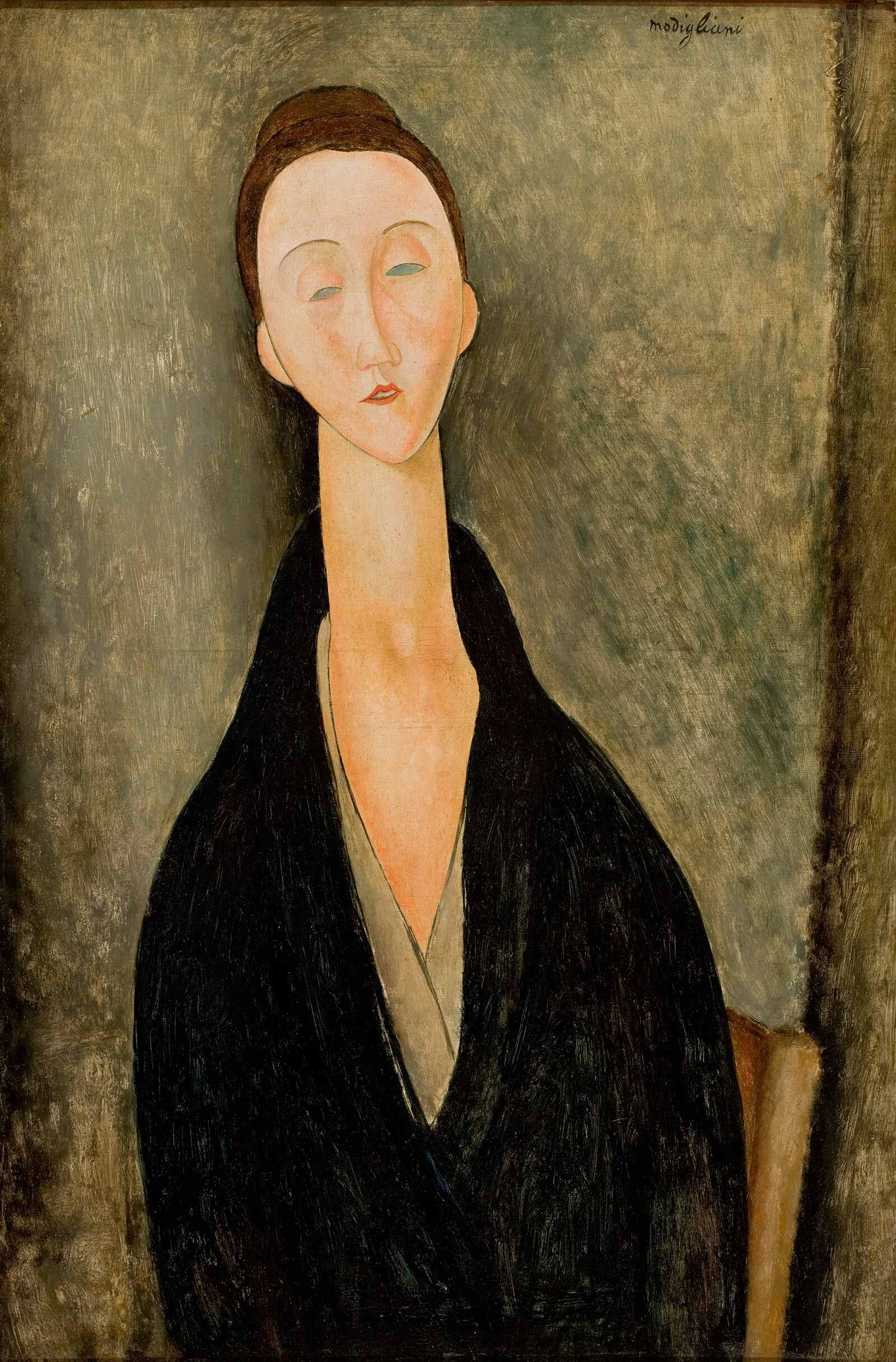

To speak formally, for a moment, it seems to me when I look back that my pursuit of ‘goodness’ was bound up, among other things, with a growing capacity to take greater risks with outline in my perception and enjoyment of images. At first, I was not greatly interested in either colour or what is now called the ‘materiality’ of the paint. Subject matter and drawing were what concerned me most, which was why a black-and-white reproduction was almost as good as the real thing. I began by liking Ingres, where the woman’s body was tightly contained within a constraining outline. I progressed towards Botticelli: despite his ‘naturalism’, his paintings had an abstracted, arabesque quality which was somehow much less insistent on being ‘real’. For example, I was fascinated by the fact that in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus you can still see where the artist changed the position of the outline of the right arm, a degree of ambivalence which would have been quite inconceivable in a major painting by Ingres. Then I became interested in Modigliani, a painter again who insists on the reality of line— where would Modigliani be without it?—but who often hints at a kind of mergence between the figure bound in by the outline and the background against which she is set. (There are some Modiglianis in which it is hard to tell whether a particular passage of paint is depicting flesh, wall, or both.) Later still, I became interested in Matisse—yes, still outline of course, but in him it becomes provocatively fluid, as tremulous and variable as we see it in the real world, rather than as rigid as the nonpainters among us often imagine it to be.

I remember that I was stimulated both to start looking seriously at modern art (which was, of course, ignored when it was not derided within the ‘19th century’ culture in which I spent my childhood) and to paint myself through a triggering contingency: seeing Tony Hancock’s film, The Rebel. I was fourteen at the time. Some of you may remember what, in truth, was a rather banal plot. Hancock plays a ‘modernist’ artist of little ability who shares a Parisian garret with a representational artist of great ability. The only thing they have in common is that they are both poor and unknown. One day, Hancock is in the garret and is ‘discovered’; however, he is assumed to be the producer of his friend’s works. These are duly exhibited and Hancock is celebrated on account of them. But soon the pressure is on him to produce more canvases of similar quality, which, of course, he cannot do. Eventually his friend, who for reasons I cannot recall colludes with the mistaken identity, supplies him with a fresh batch of works. These turn out to be abstract paintings; Hancock is horrified and convinced that ‘his’ career is finished. But the backers and critics acclaim these abstract works as loudly as they did the representational ones. Hancock, who thought it was all a question of style, shrugs his shoulders and gives up any attempt to make sense of the art world.

All right: the film was silly enough. I’m certainly not recommending it. It may well have been intended as a satire on the values of the art world, but the message I took away from it was that facility in ‘objective’ representation was not decisive. Up until this time, I had always been relatively indifferent to drawing and painting myself because I was hopelessly inept at what seemed to be the essentials of these practices, and which had indeed been taught as such in my preparatory school, i.e. mastery of such things as perspective and ‘realistic’ outline. Perhaps at this stage in my life I was simply too dissociated from the external world: anyway, I could not even begin to draw in that sort of way. But, when I saw The Rebel, it confirmed a dawning realisation that these were not the only things which counted in image making: this was given tremendous encouragement by a sympathetic art teacher at public school. And so I entered into a prodigious period of pictorial productivity which really persisted, whatever else I was doing, until I was twenty-one. This was checked, at various times, by a desire— never to be fulfilled—to master the ‘objective’ aspects of drawing. I remember my art teacher once patiently trying to teach me how to draw light and shadow using the surface of an egg as a model—at my own request. It was no use, and I gave up in despair. On another occasion, I abandoned all imaginative explorations, and tried to study artist’s anatomy, and ‘How to Draw the Nude’ books. That did not last either. These two images—both done about the same time, when I was sixteen—indicate the discrepancy between my capacity to depict, as it were, representations of objects in my ‘inner’ and in the ‘outer’ world.

As a matter of fact, that discrepancy never was resolved in terms of my practice as a maker of visual images. My ‘taste’ however did not develop in harness with my creativity. I continued to admire those who were exemplary of that which I was least able to do myself. (I spent many hours gazing at Leonardo’s drawings in a book in the school library.) Of course,

I did become increasingly interested in abstract painting; by the time I was fifteen, I had developed a passion for Mondrian. I even remember writing a poem about him in the style of Robert Browning’s marvellous ‘Fra Lippo Lippi’. Looking back on the development of my relationship to abstract art I am inclined to the view that what was important for me was the affective meaning of the space, and that there was a sense in which at times, though not often and not for long, I could do without the presence of the figure itself. At least I am aware that, once established, the trajectory of my pursuit of abstract painting closely paralleled that of my changing interest in the figure. I got to know Mondrian largely through colour reproductions: I did not realise, therefore, just how painterly some of his works are. I read him essentially as a painter of outline, an Ingres, if you like. I responded to something almost clinical, contained and restrained, linear and ‘objective’ in his ‘classical’ works. Nonetheless, it was through Mondrian that I went on to look at Kandinsky, and later still, Klee, where I felt lost in a world of almost magical transformations and transfigurations. (On looking back at the copy of Klee’s On Modern Art which I had in adolescence I was interested to note that I had underlined the words, ‘I do not wish to represent the man as he is, but only as he might be’15—an idea which was to play a central part in my later aesthetics.)

The painters I was able to appreciate last were those whose space seemed to me to be an attempt to fuse internal and external: this was, of course, something I responded to affectively (often initially by defensive boredom) rather than something I thought through intellectually. Although I looked voraciously at everything I came across, I had difficulty with impressionist painting for a long time, because the concrete world just seemed too subjectivised there, too insubstantial, too close to diffusion and dissolution. (I think the lateness of my interest in colour had much to do with this, too. Again, to speak affectively rather than epistemologically, colour seems to be the most subjective of an object’s properties; to depict the world through colour alone felt, to me, like depriving it of actuality and solidity, qualities which, psychologically speaking, were difficult enough for me to recognise anyway.) Much the same went for Cezanne, too. Cubism simply did not interest me, or enter my world, until I was at least seventeen.

But, as my interest in painting deepened, artists who were involved in this fusion came to interest me more and more. For example, among painters of the female figure whom I began to enjoy after initial indifference with what I can only somewhat pompously describe as a sense of ‘awakening goodness’ were Bonnard and De Kooning. I am not sure when I first began to like Bonnard: I saw the Royal Academy show in 1966. It must have been about that time. But it is only very recently that I have allowed myself to realise just what an important painter he is for me. In his work, the woman is entirely unleashed from her outline. Berger has brilliantly described what he calls ‘the risk of loss’ in a Bonnard painting, the fact that the figure is ‘simultaneously an absence and a presence,’ because she is ‘potentially everywhere except specifically near.’16 He describes how in a Bonnard painting one is confronted with ‘the image of a woman losing her physical limits, overflowing, overlapping every surface until she is no less and no more than the genius loci of the whole room.’17 You can see this most literally in paintings like The Open Window of 1921—and it is by no means the only one like this—where you sense the fleshly presence of a woman in the whole picture surface, but you do not at first (and sometimes not even at length) notice that Bonnard has literally included an equivocal representation of a woman, in this instance in the extreme bottom right-hand corner of the picture. Although Berger has described this aspect of Bonnard better than any other writer I have read, he is rather critical of it, indeed of Bonnard’s work as a whole.

For myself, let me just say at this stage that this apparent loss of the physical limits of the woman’s body, this restless overlapping, was, I think, what prevented me from enjoying Bonnard when I first saw his work. I was frightened by it, and I covered my fear, as is so often the case, with a veneer of indifference. Later, the painter Robert Natkin told me the story of a visit by Balthus to an art gallery where a Bonnard hung between a Picasso and a Soutine. Balthus looked at the Picasso, and then at the Soutine, and finally at the Bonnard—at which he exclaimed, ‘Ah! At last, real violence.’ I knew what he meant at once. Today I would say that it is this very indeterminacy of outline, the peculiar kind of space one gets in Bonnard which both is, and is not, based on a perspectival pictorial structure, which, in its imagery as well as through the way that it is painted fuses inner with outer—(it is no accident that one of Bonnard’s favourite themes is an open window simultaneously revealing interior and exterior, another a body almost literally dissolving in water)—that accounts for the intensity of pleasure which I can derive from looking at his works. Do you know Bonnard’s drawings? His lines at first seem to be a literal con-fusion: he seems to me to draw fluently in a way which Milner was struggling towards in that moment with her two jugs.

Pierre Bonnard, The Open Window, 1921

Now Bonnard offers a highly equivocal sort of space. When he paints a woman, an interior, or a landscape, he makes it very unclear indeed who is separate from what, what merges with whom, who belongs where, out there, or in here. I see works of this kind as almost, but not quite, the culmination of that search for ‘goodness’ which began, I suppose, when I noticed that slight blurring or warm fuzzing in the outline of the Rokeby Venus which differentiates it from Ingres, and incidentally from pin-ups. Now I am aware that much of my interest in certain ‘abstract’ painters, like De Kooning, Rothko, and Natkin, could be seen as the final step in what has been a relatively continuous, if uneven transformation of an aspect of my taste from the time when I first started poring over Ingres in reproduction. Harold Rosenberg once wrote of De Kooning that in his mature work, ‘landscapes and the human figure become in Shakespeare’s phrase “dislimned and indistinct as water”.’18In Natkin one just goes right over the edge. Outline vanishes altogether; one is confronted with a sensuous skin of paint which then bursts open into a limitless vista. One moves into a painted world where nothing is locked by line and everything exists in a boundless and plenitudi- nous state of transformation and becoming. I look upon it, and find it ‘good’, though more than a trace of the fear that would have stopped me looking at Natkin at all a few years ago remains. Now I will have a lot more to say about this change in my taste later on. Next time, I will talk in detail about the affective meanings of the space in Natkin and Rothko. But, for the moment, I want to stop here and pick up another of the pieces out of which this seminar is made. This will involve us in a little art history.

Some of you may have an idea of the particular historical perspective with which I have surrounded my art criticism over the last few years.19 However, for the purposes of our argument it is necessary to outline it briefly here.

I try never to let people forget that the idea of ‘Art’ (with a capital ‘A’) is of extremely recent origins. In England, we do not find the words ‘Art’ and ‘artists’ used in the sense in which they are used today, i.e. as referring to imaginative skills and practitioners, rather than to just any skills, until the end of the 18th century. The word ‘Art’ came into being with the rise of the middle-classes and the emergence of a professional'Fine Art tradition. The nature of the Fine Art tradition varied considerably from country to country: for example, in the Italian city states at the time of the Renaissance some artists seemed to spring directly out of the indigenous craft traditions; they were acclaimed as men of ‘genius’ and, unlike the ‘primitives’, their own name was attached to their work. In Britain, however, such immediate transcendence out of the craft traditions was not possible. The craft traditions had fallen into decadence before the waning of High Feudalism; they were obliterated through the iconoclasm of the British Reformation. Until the 18th century, fine artists were effectively imported. However, everywhere that national Fine Art traditions established themselves they were characterised by a particular training. Professional fine artists acquired the skillful use of a specific set of pictorial conventions: conventions of pose, anatomy, chiaroscuro and above all perspective. Now these were not taught as historical variables, but as being the way of depicting ‘The Truth’. Hitherto, with Berger, I have argued that these conventions equipped fine artists to depict the world from the point of view of that class which they served, and that only the exceptions tried to defy their training by, as it were, forcing the conventions they had learned to serve the point of view of another class. I still consider that there is much truth in this. Nonetheless, I would now maintain that the science of expression, as elaborated theoretically by Alberti and as practised by such artists as Leonardo and Michelangelo, had a concrete, cultural and class transcendent basis in anatomy, which prevented it from being reducible to a mere ideological instance.

It is, however, undeniable that the growth of professional Fine Art traditions was accompanied by the efflorescence of an accompanying ideology of ‘Art’ which was elaborated by artists, art historians, critics, and later museum officials. This ideology turned ‘Art’ into a transhistorical universal and projected it, together with its values, back into the earliest known social formations. As the great archaeological discoveries of the 19th century were made, fine artists came more and more to see themselves as the consummation of an unbroken continuum of ‘Art’ stretching back from the Royal Academy to prehistoric caves.

However, the reality behind this ideological mystification was rather different. Although in every known civilisation men and women had always made visual images of one sort and another, they had done so in a great variety of different ways, and these images had served a multitude of different functions. (Nonetheless, and this is a point insufficiently emphasised in my previous analyses, certain specific practices, most notably painting and sculpture, can be shown to have a material continuity since the beginnings of human civilisation.) Prior to the rise of the professional Fine Art traditions, there was no equivalent of either ‘art’ or artists; but Fine Art’s mystification of itself allowed it to disguise the fact that its status was changing profoundly with the development of new means of visual image making—like photography and lithography. These really came into their own when monopoly capitalism displaced the old entrepreneurial capitalist system, and the bourgeoisie as a progressive class began to wither. Associated with the emergence of monopoly capitalism was the efflorescence of what I have designated as ‘The Mega-Visual Tradition’: by that I mean that whole welter of means of producing and reproducing images which includes not just photography, mass colour printing, lithography, and holography, but the moving pictures of cinema and television, too. Indeed, I argue that just as free-standing oil painting was the dominant form of static visual imagery under entrepreneurial capitalism, advertising is the dominant form of static visual image making under monopoly capitalism.

Now this process of displacement of the old Fine Art tradition from the task of conveying the world-view of the bourgeoisie initially had the effect of opening up possibilities for the imaginative artist. He was no longer pinned down within a particular ‘visual ideology’. For a very brief period— roughly from the time of Cezanne’s maturity in the 1880s until the death of Cubism — what I would characterise as a ‘progressive’ Modernist movement (or rather plethora of related movements) thus came into being.

Certain of the artists in some of these movements attempted—in some instances consciously, in others not—to act as visual prophets of the new world order which they felt was in the process of coming into being. We must not forget the exhilarating promise which seemed to be implicit in the advance of the bourgeoisie throughout the 19th century, a promise which seemed to be on the very threshold of realisation in the technological progress associated with emergent monopoly capitalism. An attainable vision of the transformation of the world into a place where the problem of need had been solved and natural resources fully socialised seemed to be at hand. I agree with Berger when he depicts Cubism as an attempt (even if it was not recognised as such by those engaged in it) to struggle out of the old perspective-based Fine Art conventions towards a half-expression of a new way of seeing and representing the world appropriate to what seemed to be the new, emergent world order.20 Actually, this initiative was smashed to pieces by the First World War and the long, and still continuing, series of historic calamities and catastrophes which put an end, forever, to hopes for a peaceful, ‘evolutionary’ transition to the new Utopia.

By and large, it is possible to characterise Modernism after the decline and disillusionment of the great avant-garde movements as a retreat, by artists, from even the attempt to articulate a historic world-view to replace the now displaced 19th century, middle-class optic and perspective. The reasons for this retreat appear to have been two-fold: on the one hand, history seems simply to have dazed and outstripped artists; on the other, the ‘Mega-Visual Tradition’ continued to pump out an ever escalating quantity of banalising lies as the century progressed, swamping, marginalising, disrupting and eclipsing the products and practices of fine artists.

Thus Berger has described most post-First-World-War Western Art as a sort of epilogue to the European and American 19th century professional Fine Art traditions, an epilogue in which painting is reduced to a dialogue with itself, about itself, because there is no other area of experience upon which it can touch meaningfully, except itself. I have elaborated the notion of the kenosis or self-emptying of the Fine Art tradition: kenosis is a term I borrowed from theology. I am using it to refer to the apparent relinquishment of the professional and conventional skills by Fine Artists and to the abandonment of the omnipotent power the painter once seemed to possess to create, like God, a whole world of objects in space through illusions on a canvas. I see this general kenosis as having been ruptured at various points—most notably after the Second World War in Europe, New York, London, Chicago and elsewhere—by tremendous outbursts of expressionism in which artists attempted to find ways of speaking meaningfully of their experience, including historical experience, once more. Nonetheless, the process of kenosis, with these occasional regenerative hiccups, proceeds.

That is the historical perspective which underlies my critical practice. By and large, it still seems to me to be a truthful and a useful analysis. But I now want to modify it slightly. I want to approach the problem in a rather different way.

To this end, I now wish to produce the next fragment of that statue which I am piecing together. It consists of a book by Clive Bell, called simply Art, first published in 1914, that pivotal year in the destiny of the old professional Fine Art traditions and, as it turned out, of much else besides. Together with Roger Fry, Bell is often regarded on the Left as the source of all the trouble. Fry and Bell are seen as the theoretical precursors of the self-critical formalism of late Modernism. In them, we find the elaboration of the idea that ‘Art’ constitutes an autonomous, self-contained, entity which we can only truly experience if and because it evokes in us certain types of sui generis emotion, which have nothing to do with other human emotions, or with lived experience beyond the experience of art. Art, they maintain, should thus be appreciated without reference to the representational, psychological, social, political, religious, or other non-aesthetic considerations which it might evoke.

Let me say straight away, to preclude the possibility of misunderstanding, I am absolutely not about to re-habilitate Bell: he was opinionated, arrogant, ultimately down-right reactionary—one of the nastiest weeds to have flourished in Bloomsbury, and he got it all (or almost all) wrong to boot.21 But equally, if I am not going to rehabilitate Bell, I am not going to kick him either: that would be much too easy. The brand of aesthetic formalism to which his kind of critical thinking gave rise has been getting an atrocious press recently. Formalism is no longer a cultural danger or a worthy opponent. On the other hand, I would maintain not just that Bell’s book is a key text in the emergent ideology of late Modernism (which it is), but also that embodied within it are kernels of truth which have escaped almost all of those who have put forward critiques of formalism from left positions. With a little help from psychoanalysis, I want to isolate one of those kernels of truth, to extract it, unravel it, and preserve it. It not only constitutes something germane to my argument, but also that which ‘Social Criticism’, the rising orthodoxy, seems in danger of losing sight of altogether.

Let me explain.

Bell claims to offer ‘a complete theory of visual art’, and in many ways it is a very simple theory. He argues that ‘all works of visual art have some common quality, or when we speak of “works of art” we gibber.’22 He then asks, ‘What is this quality? What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions?’ And he arrives at what seems to him the only possible answer:

‘—significant form. In each, lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions. These relations and combinations of lines and colours, these aesthetically moving forms, I call “Significant Form’’; and “Significant Form” is the one quality common to all works of visual art. ’23 You can spot right away the sort of clangers which this rope of reasoning is going to wring from our Bell. What can be the status of ‘works of art’ which fail to stir his aesthetic emotions? According to the theory, they must lack Significant Form, and therefore, cannot by definition, be thought of as works of art at all. It is, I suppose, to Mr. Bell’s credit that he pushed this view through to its logical conclusion: most works of art are not works of art at all. The book is peppered with such observations as:

‘I cannot believe that more than one in a hundred works produced between 1450 and 1850 can be properly described as a work of art.’24 Or again:

‘. . . the Impressionists raised the proportion of works of art in the general pictorial output from about one in five hundred thousand to one in a hundred thousand. . . . Today I daresay it stands as high as one in ten thousand.’25 You also quickly come to realise that whatever stirs Clive Bell’s aesthetic emotion, it is not the products of the professional Fine Art tradition. It is no exaggeration to say that Bell had an almost hysterical disregard for the Renaissance (although he modified this position in his later works) and especially for its discovery of perspective. He calls the Renaissance ‘a strange new disease’, and ‘nothing more than a big kink in a long slope’. He often makes such comments as, ‘the decline from the 11th to the 17th century is continuous,’ or, ‘more first-rate art was produced in Europe between 500 and 900 than was produced in the same countries between 1450 and 1850,’ or:

‘This alone seems to me sure: since the Byzantine primitives set their mosaics at Ravenna no artist in Europe has created forms of greater significance unless it be Cezanne. ’26 Now the curious thing about the way in which Mr. Bell argues is that it is precisely ‘Art’ (with a capital ‘A’) in the historically- specific sense which he effectively denies to be art at all. Art, for Bell—i.e. that which stirs his aesthetic emotions—flourished among the so-called European Primitives of the Dark and Middle Ages, was all but extinguished by the Renaissance and that which followed it, and came to life again with Cezanne who ‘founded a movement’, a movement which Bell (writing before the First World War at a time when he would still have described himself as some sort of socialist) described as ‘the dawn of a new age’.

What did Bell have against the Renaissance? Well, he felt that during it ‘Naturalism’ and ‘Materialism’ had driven out what he called ‘pure aesthetic rapture’. He compalined that in the art of the Renaissance, ‘intellect is filling the void left by emotion’, and that the work of artists was being supplanted ‘by Science and culture’. These things, in Bell’s view, had nothing at all to do with art: he was even more scathing about 17th century Holland, another place where, he felt, art barely existed at all. ‘We have lost art,’ he wrote of Dutch painting of this period, ‘let us study science and imitation.’27 In short, he complains that ‘the outstanding fact is that with the Renaissance Europe definitely turns her back on the spiritual view of life.’28 Bell could not even accept the Impressionists, because, in his view, they were too scientific.

At this point, I simply want to raise the fact that Bell’s view of art is exceptionally close to his conception of religious experience. He says that ‘Art and religion belong to the same world. Both are bodies in which men try to capture and keep alive their shyest and most ethereal conceptions. The kingdom of neither is of this world.’ He describes art as ‘an expression of that emotion which is the vital force in every religion . . . We may say that art and religion are manifestations of man’s religious sense if by “man’s religious sense’’ we mean his sense of ultimate reality.’2'' At one point, he even exclaims, ‘from the beginning art has existed as a religion concurrent with all other religions.’

Is all this, as Bell himself might have said, mere ‘gibbering’? In one sense, yes, I am afraid that it is: but, like religious piffle itself, it does contain that vital kernel which I referred to earlier. It is not enough simply to laugh at Bell and to throw ‘aesthetic emotion’ otlt of the window as so many of both the ‘left’ social critics and ‘right’ formalists have done. We have to do to Bell’s aesthetics what Feuerbach did to Christianity: we have to invert them, to locate the experiences which they describe in this world, to resolve them into their anthropological and biological determinants. I think this may be possible. For the moment, let us leave Bell with a passage in which he contrasts ‘the superb peaks of aesthetic exaltation’ with ‘the snug foothills of warm humanity’. The latter, he writes, is ‘a jolly country’:

‘No one need be ashamed of enjoying himself there. Only no one who has ever been on the heights can help feeling a little crestfallen in the cosy valleys. And let no one imagine, because he has made merry in the warm tilth and quaint nooks of romance, that he can even guess at the austere and thrilling raptures of those who have climbed the cold, white peaks of art.’30

We will return to examine those thrilling raptures and those cold white peaks later, but I hope that by now at least some of you will be beginning to see where all our threads are going to be tied. I am suggesting that there is something significant in common between the difficulties Milner had with perspective and outline; the development of my taste from Ingres to Natkin and Rothko; the historical crisis in the Fine Art tradition; and Bell’s rejection of the most characteristic products of that tradition in favour of raptures on those cold, white peaks. That something was not just a retreat from experience: it was also a retrieval of it.

You will remember that I made some reference to Adrian Stokes’ ideas about ‘modelling modes’ and ‘carving modes’—a distinction which, of course, he regarded as being as relevant within painting as sculpture. Stokes, a Kleinian, tended to associate the carving mode with ‘the depressive position’, with the separateness, autonomy and otherness of the object; whereas he links the modelling mode with the ‘paranoid- schizoid’ position, with flatness, decoration, and failure to establish a separate identity, or to recognise the distinction and space between the self and the mother.

For a moment, I want to talk in gross generalities. I want to say, preposterously, that, prior to the Renaissance, the ideology of space and its representation in visual images was essentially a projection of the fused and con-fused infantile space of what Stokes calls the ‘paranoid-schizoid’ position. Before I make what I mean by this a little clearer, I want to offer a warning: it is very difficult indeed for us to think ourselves back into an earlier spatial system, whether we are talking about an historical, or a biographical-developmental one. The commonest mistake when attempting to do so is to assume that the spatial system out of which one is, oneself, operating must have dawned upon those who first began to discover it like a self-evident truth, whereas in fact, of course, they felt it as a violent disruption of self-evident truths.

Let me give you a good example of this. Writing in 1876, Leslie Stephen commented on how the emergence of a new cosmology through the rise of modern science changed men and women’s perception of themselves and their world:

‘Through the roof of the little theatre on which the drama of man’s history had been enacted, men began to see the eternal stars shining in silent contempt upon their petty imaginings. They began to suspect that the whole scenery was but a fabric woven by their imaginations. ’31 Now that image seems to me vivid and good: but what is interesting is that elsewhere in the same book, speaking of his own late Victorian age, which was the inheritor of a world in which the old stage cloths had finally been, if not torn down, then ripped to shreds, Leslie Stephen could write:

‘Our knowledge has, in some departments, passed into the scientific stage. It can be stated as a systematic body of established truths. It is consistent and certain. The primary axioms are fixed beyond the reach of scepticism; each subordinate proposition has its proper place; and the conclusions deduced are in perfect harmony.’32

In other words, he saw the Victorian scientific world-view in very much the same way that a medieval school-man regarded his own cosmological world-view as a ‘systematic body’ of eternal truths existing in ‘perfect harmony’. Stephen, perceptive as he was, had no intimation of the fact that within thirty years of writing this passage, his cosmology would begin to be devastated as thoroughly as when Newtonian science finally revealed the ‘imaginary’ character of the medieval world-view. In the first of these seminars, we considered the way in which that water-shed of history, the First World War, was associated with the disintegration of the Victorian way of conceiving of the world, part of which was the rise of a new physics which put everything once more well within the reach of scepticism.

With that warning, let us turn to a text by the mathematician Kline about ‘early Christian and medieval artists’ who, he says:

‘. . . were content to paint in symbolic terms, that is, their settings and subjects were intended to illustrate religious themes and induce religious feelings rather than to represent real people in the actual and present world. The people and objects were highly stylized and drawn as though they existed in a flat, two dimensional vacuum. Figures that should be behind one another were usually alongside or above, Stiff draperies and angular attitudes were characteristic. The backgrounds of the paintings were almost always of a solid colour, usually gold, as if to emphasize that the subjects had no connection with the real world.’33

That sort of description of medieval art seems true enough to us: essentially, I think that it is true; but it also leaves out of the account the degree to which the medieval painting was a depiction of ‘the real world’ as the medieval painter conceived it. Certainly, medieval painting is highly conventionalised, but then, as we have seen, outline and perspective are themselves conventions. It may be that there was a much greater correspondence than this quotation implies between the flat, planar earth of medieval cosmology, with its ascending and descending angels not subject to the laws of gravity, and its over-arching dome of a heaven above, and a hell below, and the flat, two-dimensional, ‘unreal’ way in which the painter depicted the world. I suspect that there is a sense in which the space in medieval paintings is expressive of the way in which men and women felt themselves to be within their world. We must therefore be careful when we say that the medieval painter worked ‘in symbolic terms’. Such statements are not entirely untrue. However they greatly over-emphasise the degree to which the painter conceived of the ‘real’ world in one way and then turned away from it and set about painting another ‘unreal’ or ‘religious’ world of symbol.

What I am saying is, of course, that the medieval painter was—as Milner put it when she had problems with perspective—much more mixed up with his objects than were the painters of the Renaissance. He made much less distinction between internal and external space—and religious ideology encouraged, indeed enforced, this confusion. Religious cosmology was effectively the institutionalised version of a projection of a subjective space into the real world. Up there, you have the good heaven with its sustaining "and nurturing deities; down there, the bad hell into which all one’s own evil, destructive and aggressive impulses can be projected. The ‘real world’ is no more than an integral part of this system, which is freely peopled with ‘good’ and ‘bad’ father and mother imagos, and with winged and weightless creatures representing benign impulses, and hooved and cloven ones standing for bad. This, of course, is what I mean when I say that the conception of space prior to the Renaissance was, if we accept the Kleinian terminology, ‘paranoid-schizoid’.

The Renaissance changed that. To persist with our extravagant generalisations, the Renaissance involved that sifting out of mind from matter, of self from other, that recognition of space, distance and separateness which in individual development characterises the achievement of the ‘depressive - position’. Evidently, this can today be seen most clearly in those Renaissance paintings in which the conventional means were found for the introduction of the third dimension, that is, the rendering of recessive space, of distance, volume, mass, and visual effects. The initiation of these conventions, particularly through the re-creation of perspective, is, for me at any rate, what makes the painting of Duccio, Giotto, Lorenzetti, and Van Eyck so exciting. By the early 15th century, in the work of Brunelleschi—the elaborator of a complete system of focused perspective and the tutor of Donatello, Masaccio, and Fra Filippo—painting became very like a science; not only was it based upon its own laws and mathematical principles, but it had also become a significant means for the investigation and propagation of knowledge about the external world.

Perspective, too, was conventional; I do not wish to be thought to be saying that it allowed ‘truthful’ representations of the ‘real’. Like the medieval spatial representations before it, perspective did not even represent as the eye sees:

‘The principle that a painting must be a section of a projection requires . . . that horizontal lines which are parallel to the plane of the canvas, as well as vertical parallel lines, are to be drawn parallel. But the eye viewing such lines finds that they appear to meet just as other sets of parallel lines do. Hence in this respect at least the focused system is not visually correct. A more fundamental criticism is the fact that the eye does not see straight lines at all . . . But the focused system ignores this fact of perception. Neither does the system take into account the fact that we actually see with two eyes each of which receives a slightly different impression. Moreover, these eyes are not rigid but move as the spectator surveys a scene. Finally, the focused system ignores the fact that the retina of the eye on which the light rays impinge is a curved surface, not a photographic plate, and that seeing is as much a reaction of the brain as it is a purely physiological process. ’

As I have already suggested, perspective also became inflected by the class interests of those whom the professional artists who elaborated, practised and developed it, served. Nonetheless, when all this has been said, it remains true that perspective was essentially an attempt to explore the character of the world out there, the external world, and the properties and material relations through which exterior space was constituted. Technically, perspective involved a literal carving, pushing or cutting back through the surface of the picture plane. Neither artists, nor other men and women, were any longer so ‘mixed up’ in the objects which they perceived. Affective representations of space became increasingly rare.

As Bell perceived, we can (ignoring for a moment all the possible exceptions, of which there are many) say crudely that this separation out of men and women from the ‘paranoid- schizoid’ space of the medieval world characterised the task of the painter from the decline of Primitive Christian Art (which, you will recall, Bell loved) to the rise of Cezanne (whom he also loved). Michelangelo’s paintings, for example, seem to me in general less masterful than his sculptures because, in the paintings, he is, as it were, endeavouring to constitute ‘real’ bodies within what is essentially the older spatial modality and mythology.) During the long period from the rise of the Renaissance, until the emergence of Modernism, painters were, to continue with the Kleinian terminology, working through, or at least within, the ‘depressive position’.

At the time of Cezanne, however, we have already seen that the ideological obligation upon artists to elaborate an external world-view was rapidly diminishing. As the painter’s cultural position was usurped through the rise of the Mega-Visual tradition, he became in one sense at least, freer. I would also emphasise that, by the end of the 19th century, with the emergence of a new physics—i.e. a new conception of the nature of the physical world—and the transformation of science, the old system of ‘objective’ perspective representation was itself exposed, except for those who were ideologically overcommitted to it, as largely a conventional and historically relative means of representing the world. This was one reason why, as we saw in the first seminar, the generation of Freud’s mechanist teachers became interested in the depiction of movement. But, evidently, the camera and film played a large part in that too.

At this point, I want to raise a question mark about Cezanne. Much has been written about Cezanne by other Marxist writers, for whom I have the greatest respect. One theory suggests that Courbet produced a ‘materialist’ view of the world; Cezanne a ‘dialectical’ view; and the Cubists a 'dialectical materialist view. ’ It is a ‘nice’ argument, but I am not sure that it is entirely true.

Certainly, Cezanne’s work poses a new kind of relationship between the observer and the observed: it is with Cezanne that we begin to be made aware that what I see depends upon where I am and when. He shows us landscape in a state of change and becoming, from the point-of view of an observer who is himself no longer assumed to be frozen and motionless in time and space. But I wonder whether this perceptual reading of Cezanne is not sometimes greatly over-done. Perhaps the real sense in which Cezanne was ‘The Father of Modern Painting’—and certainly the sense in which writers like Bell responded and over-responded to him — was that for the first time since prior to the Renaissance, Cezanne mingled a subjective with an objective conception of space, but of course he did so playfully and in an explorative rather than a dogmatically decreed fashion. Bell, it is worth noting here, constantly emphasises in his book, Art, that what he takes to be the ‘religious’ component of Christianity can be separated out from its dogma: ‘religion’was, for him, the perception of this mingling of inner and outer. Thus, too, Greenberg writes of Cezanne, ‘What he found in the end was, however, not so much a new as a more comprehensive principle; and it lay not in Nature, as he thought, but in the essence of art itself, in art’s “abstractness”.’35 I consider that what Greenberg calls here its ‘abstractness’ is its capacity to be expressive of psychological experience. What we get from Cezanne, I would suggest, is exactly that sensation which Milner was looking for, that ‘some kind of relation to objects in which one was much more mixed up with them’ than classical, focused systems of perspective allowed.

Interestingly, it was the abstract painter Robert Natkin, of whom I will have more to say next time, who first led me to perceive this aspect of Cezanne when he pointed out how, in many of Cezanne’s paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, something very peculiar goes on between the foreground and the background of the picture. At moments a branch on a tree in the front seems to be depicted only feet away from others; but soon after, it seems to touch the slopes of a mountain which is ‘in reality’ twenty miles or so away. This sort of playful toying with his perception of the external world, which involves both the acceptance and also the denial of distance and separation, seems to me to have a lot more to do with the re-introduction of certain kinds of affects into painting than with Cezanne’s perceptual responses alone.

This is confirmed, I think, when one considers the theme of naked figures in a landscape, with which Cezanne was always fascinated. Towards the end of his life the way in which he handled this subject changed; he became less interested in the eroticism of appearance. Although each of the figures in his groups retained its autonomy, Cezanne sought ways of representing them in which they were simultaneously indissoluble from the ground, water, sky and trees which surrounded them. Women Bathing was painted within four years of his death: although the whiteness of the canvas surface plays its part, the painting is anything but loose or unfinished.

Cezanne made it in his studio; if he relied on petites sensations they were in the form of memories, rather than of things immediately seen. Anyway, he learned as much from looking at Poussin as at Provence. Like Poussin, Cezanne offers an attempt at a total view of man-in-nature, but it is a very different kind of view from that of the 17th century master. Cezanne refuses focused perspective and breaks up and re-orders his picture space in a radically new way. His memories have been realised, through an elaborate structuring of coloured planes, into a vision of a new kind of relationship between human beings and the natural world which they inhabit. Poussin’s totalisation was one of eternal stasis. Cezanne’s (although, as I shall argue, it involves a retrieval of affects belonging to an early phase of life) is essentially a promise, characterised by becoming. It revives the emotions of his individual past, to speak of a possible transformed future.

Paul Cezanne, Grandes Baigneuses, 1899-1906.

And now, I hope, you will be beginning to see the point I am getting at. Although the modern movement failed, for reasons we have already explored, to realise a new ‘world-view’ through painting, in the work of Cezanne himself and of at least some of his successors —e.g. Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, Bonnard, Klee, and later De Kooning—it did re-introduce to painting an aspect which had been absent from it, or at least heavily muted, during the era of the dominance of professional Fine Artists. These early modernist painters certainly acknowledged the external otherness, the separateness and ‘out- thereness’ of the outside world, but having acknowledged it, they sought to transfigure and transform it, to deny, or otherwise to interrupt it, as a means of expressing subjective feelings too. Their new forms emerge as neither an indulgence nor an escape from the world, but rather as an extension into an occluded area of experience.

Now I think that it was only when painters attempted to do this that Bell experienced his ‘aesthetic emotion’, those strange indefinable yearnings on which he places such great importance. But the point is that this was actually a new thing for those who made visual images to explore and to attempt to do. Bell made the mistake of identifying this as the essence of ‘art’, universalising it, and projecting it back through history, so that any work which did not show this quality could be dismissed as not really worth looking at. (Bell wrote off not just the ‘worldview’ painters of the Renaissance, of 17th century Holland and of 19th century England, but also, of course, those who were trying to elaborate new world-views through painting in the 20th century—the Futurists and Vorticists, for example.)

This leads us to an important point. Stokes’ taste, for most of his life, was for work in the ‘carving mode’, for art in which the depressive position had been worked through, for the Quattrocento and the High Renaissance. Bell’s taste, on the contrary, was for the modified ‘modelling mode’ (though of course the terms would have been quite foreign to him) for the Christian Primitives and the Post-Impressionists, for an art which as it were, pushed back even further emotionally from the ‘depressive position’ towards the prior ‘paranoid-schizoid’ position. (Actually, this polarisation is not fair to either of them. As I said last time, unlike many Kleinian aestheticians, Stokes was prepared to recognise the importance of feelings of mergence and fusion in aesthetic experience. In later life, he became ever more sympathetic to the modelling modes. Whereas Bell, of course, modified his vituperative dismissal of Renaissance ‘world-view’ painting.)

Bell disguised this. He insisted that he was talking about an autonomous, irreducible aesthetic experience, when in fact he was responding to the capacity of a certain type of visual image to evoke and arouse a certain type of relatively inaccessible—not everyone, he stressed, was capable of aesthetic sensibility— human emotion which he and (I better admit it) I, too, find intensely pleasurable. The nature of that exquisite aesthetic emotion is, I think, rendered all but manifest in that passage about the raptures that can be experienced upon the cold white peaks of art. Bell found in the modern movement, and enjoyed there, a capacity of painting to revive something of the spatial sensations and accompanying ‘good’ emotions which the infant feels at his mother’s breast. By this, however, I mean much, much more than that Bell liked art because he found it to be a symbol of the ‘good’ breast in the Kleinian sense. Let me explain.

Bell’s Art is full of indications of resistance: he is peculiarly keen on dismissing any attempt to penetrate or reduce aesthetic emotion. He also engaged, as one might expect, in polemic against psychoanalysis. For example, in a communication called ‘Dr. Freud on Art’, Bell tells how he once begged a roomful of psychoanalysts,

'. . .to believe that the emotion provoked in me by St. Paul’s Cathedral has nothing to do with my notion of having a good time. I have said that it was comparable rather with the emotion provoked in a mathematician by the perfect and perfectly economical solution of a problem, than with that provoked in me by the prospect of going to Monte Carlo in particularly favourable circumstances. But they knew all about St. Paul’s Cathedral and all about quadratic equations and all about me apparently. So I told them that if Cezanne was for ever painting apples, that had nothing to do with an insatiable appetite for those handsome but to me unpalatable, fruit. At the word “apples” however, my psychologists broke into titters. ’

Yes, the word was ‘titters. ’

‘Apparently, they knew all about apples, too. And they knew that Cezanne painted them for precisely the same reason that poker-players desire to be dealt a pair of aces.'"’

It is not clear whether Bell was aware of the transparency of the symbolisation he recorded here. In any event, he goes on to say that the real reason Cezanne used apples was because ‘they are comparatively durable’ (unlike flowers) and can be depended upon ‘to behave themselves’ (unlike people). If this story is correctly reported, it is hard to say who was the more stupid: the tittering analysts who uncritically interpreted the figurative elements in Cezanne’s painting as being straightforward breast symbols; or Bell himself. What we need to ask of psychoanalysis is not a capacity to unmask subject matter or manifest figurative symbols in painting, but rather whether it can help us to understand those subjective spatial representations which begin to appear with the rise of Modernism, and with Cezanne. I think that psychoanalysis does have much to contribute here, or, to be more exact, I think there is much to be learned from a particular tendency within psychoanalysis, the British object relations school, to which Milner, for example, belongs. But before I can clarify this, I have to produce another fragment from my bag of pieces, and that is a short chunk of psychoanalytic history and theory.

Some of you may have noticed the direction in which we are moving through this series of seminars. In one sense, this corresponds simply enough to the chronological development of psychoanalytic theory. We begin with Freud; we moved on to Klein; and now we are about to find ourselves standing in the clear, bright light of British ‘object relations’ thought. But this trajectory also corresponds to an inverse chronology of human development. My first paper, with Moses as its focus, revolved around aspects of the infant-father relationship and its survivals in adult life. In my second paper, we were involved with the mother, albeit as an ‘internal object’, and the nature of the reparative processes which could be lavished upon that object when it was felt that it had been damaged or destroyed through the subject’s own hate and aggression. In these last two sessions, we are concerned with the earliest infant-mother relationships, but we are focusing on the nature of the infant’s experience before he (or she) has become fully aware of himself (or herself) as a being separated from the mother or the world.

Moses by Michelangelo

I want, now, to return to the British School, and to sketch out aspects of the way in which theory developed there after the arrival of Melanie Klein. You will recall that Freud himself conceived of the infant as auto-erotic and narcissistic. In Freud’s view, the baby was motivated by the desire to secure instinctual pleasure by evading tension. Freud postulated three phases of libidinal development—oral, anal, and phallic—prior to the Oedipal conflict and the emergence of so-called ‘genital sexuality’ involving the desire for objects outside the self. Freud supposed that the infant was only interested in the mother insofar as she served the purposes of the child’s auto-erotism, by gratifying instinctual desires such as that for food. As a matter of fact, Freud had only the dimmest conception of the nature of the infant’s relations to the mother, which he did not discuss until as late as 1926. Indeed, Freud often writes as if the relationship with the father was more important. (The reasons for Freud’s blindness in this respect were at least in part defensive; he never satisfactorily analysed his relationship with his own mother, a fact which led to distorted inflections in his theoretical formulations. There were also cultural factors: given the relative status of fathers in the 19th century, European, middle-class homes, Freud was often unable to see beyond the authority of Moses. As we saw, he was indifferent to the Venus.)

Venus De Milo

Klein’s theories, evidently, were in this respect a real advance on Freud’s. Klein gave a centrality to the infant’s early relationship with the mother, to the degree that, as Brierley put it, Freud’s more orthodox followers found it ‘difficult to reconcile Melanie Klein’s assumption that the infant very soon begins to love its mother, in the sense of being concerned for her, with Freud’s conception that in the earliest months the infant is concerned with its environment only in relation to its own wishes.’37 Nonetheless, despite Klein’s formal assurances to the contrary, it remains true that in her system the course and character of this relationship is determined not so much by the quality of the mothering which the child receives as by the way in which the child plays out its innate, instinctual ambivalence. As we have seen, Klein was concerned with what she took to be the working out of an instinctual opposition between love and hate, which was not greatly affected by the nature of the environment. In general, Klein emphasised, indeed overemphasised., orality, feeding, etc. As Guntrip puts it, ‘Mrs Klein states that “object-relations exist from the beginning of life”. . . but this seems to be something of an irrelevance; it does not matter much whether they do or not if they are merely incidental to the basic problems. ’38

A decisive step in psychoanalysis, however, was the replacement of dual instinct theory, whether of the Freudian or Kleinian variety, by a full object relations theory, i.e. by a theory in which the subject’s need to relate to objects plays a central part. Psychoanalysis arrived at this focus in Britain long before it did so elsewhere. (Only during the 1960s did some American analysts also become involved in this area of work.) The way in which this came about involved a number of disparate, and often seemingly incompatible strands and elements. Flere, I can only sketch a few of the more significant.

Some came from the serious critiques of psychoanalysis which were being elaborated outside the movement itself. For example, in the 1930s, analysts were often involved in theoretical jousting with members of the Tavistock Clinic. (Glover has written that within the British Psychoanalytic Society, ‘suggestions that a closer contact might be made even with more eclectic medico-psychological clinics, such as the Tavistock Clinic, were frowned on.’)39 Nonetheless, at the Tavistock, J. A. Fladfield, who was far from totally rejecting analytic findings, argued against Freud’s auto-erotic conception of infancy that the fundamental need of children was for protective love. In the early 1930s, Ian Suttie was one of Hadfield’s assistants. Suttie died at the age of 46, in 1935, but the following year his critique of Freud’s psychology, The Origins of Love and Hate, was published.

Suttie provides a systematic account of man as a social animal, whose object-seeking behaviour is discernible from birth. Suttie abandons Freud’s concept of Narcissism arguing that ‘the elements or isolated percepts from which the ‘‘mother idea” is finally integrated are loved (cathected) from the beginning.’ Thus Suttie found it possible to speak of the infant’s love for an external object, the mother, from the earliest moments of life. This was not sentimentalisation of the infant-mother relationship; he identified its biological basis clearly:

‘I thus regard love as social rather than sexual in its biological function, as derived from the self-preservative instincts not the genital appetite, and as seeking any state of responsiveness with others as its goal. Sociability I consider as a need for love rather than as aim-inhibited sexuality, while culture-interest is derived from love as a supplementary mode of companionship (to love) and not as a cryptic form of sexual gratification.’41 Suttie was not approved of by the psychoanalytic establishment in his life-time. Today, however, many of the criticisms he made of Freud—including his observations of the latter’s ‘patriarchal and antifeminist bias’—are very widely accepted, even within the psychoanalytic movement itself. Indeed, by the 1940s, hostility between the Tavistock and the Institute of Psychoanalysis was diminishing. For example, John Bowlby was analysed by Joan Riviere, one of Klein’s foremost followers; Klein herself was one of his supervisors when he was a trainee analyst. In 1946, Bowlby joined the Tavistock, without relinquishing his psychoanalytic associations. Bowlby was further strongly influenced by the work of ethologists, especially Tinbergen and Lorenz. Bowlby acknowledges a debt to Suttie, but in his own work he elaborated a. thorough-going critique of Freudian instinct theory: ‘in the place of psychical energy and its discharge, the central concepts are those of behavioural systems and their control, of information, negative feedback, and a behavioural form of homeostasis.’42 Bowlby strongly opposed the idea that the infant’s relationship to the mother was based on primary need gratification, such as the wish for food. Bowlby emphasised the need for ‘a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship’ with the mother ‘in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment’. He held that the ‘young child’s hunger for his mother’s love and presence was as great as his hunger for food.’4' Although retaining psychoanalysis as his frame of reference, Bowlby drew on a mass of empirical data from other disciplines. The fact that he stands at the intersection between psychoanalysis, behavioural studies, ethology, biology, and contemporary communications theory should have rendered his work of enormous significance to all of us on the left who are looking for a rigorously materialist account of the early infant-mother relationship. Instead, socialists have tended to revile his work without attending to it but that is another story.

Other influences were also inflecting the unique course which psychoanalytic theory was taking in Britain. You may remember that in my last seminar, I referred to Sandor Ferenczi, a close colleague of Freud’s until his latter days, and Klein’s first analyst. Ferenczi was the leader of the psychoanalytic community in Budapest, until his death in 1933. Guntrip has accurately described the differences between Ferenczi and Freud, differences which were to have tragic consequences for the former:

‘Ferenczi recognised earlier than any other analyst the importance of the primary mother-child relationship. Freud’s theory and practice was notoriously paternalistic, Ferenczi’s maternal- istic. His concept of "primary object love” prepared the way for the later work of Melanie Klein, Fairbairn, Balint, Winnicott, and all others who to-day recognize that object-relations start at the beginning in the infant’s needs for the mother. Ferenczi held that this primary object-love for the mother was passive, and in that form underlay all later development.’44 Many of those gathered round Ferenczi developed his approach. Hermann, for example, pointed towards such components in the infant’s relation to the mother as clinging and clasping, which could not be accommodated within the traditional Freudian perspective. Alice and Michael Balint began to develop a more radical critique of Freud’s theory of narcissism, but Hermann’s observations enabled them to progress beyond Ferenczi’s essentially passive conception of the infant’s relation to the mother, to a fuller characterisation of this ‘archaic’, primary object-relation. In the Balints’ view, the infant was ‘born relating’, even if its mode of loving was egotistic.45 Early object relations possessed autonomy from erotogenic activities. The Balints came to live and work in Britain, where their ideas had a considerable influence'among some Kleinians.

But, within Kleinian circles, parallel critiques and extensions of classical theory had already sprung up independently. Among the most significant was that put forward by W. R. D. Fairbairn, an analyst who, in the middle and late 1930s, was strongly under the influence of Klein. However, between 1940 and 1944, Fairbairn published a series of controversial papers— including, ‘A Revised Psychopathology of the Psychoses and Psychoneuroses’ of 194 1 46—in which he essentially revised psychoanalytic theory ‘in terms of the priority of human relations over instincts as the causal factor in development, both normal and abnormal’. Fairbairn described libido as not pleasure-seeking, but object-seeking; the drive to good object relationships is, itself, the primary libidinal need. In the words of Guntrip, his most devoted disciple: