Introduction by Laurence Fuller

Lot's Wife from La Petite Mort by Marcelle Hanselaar

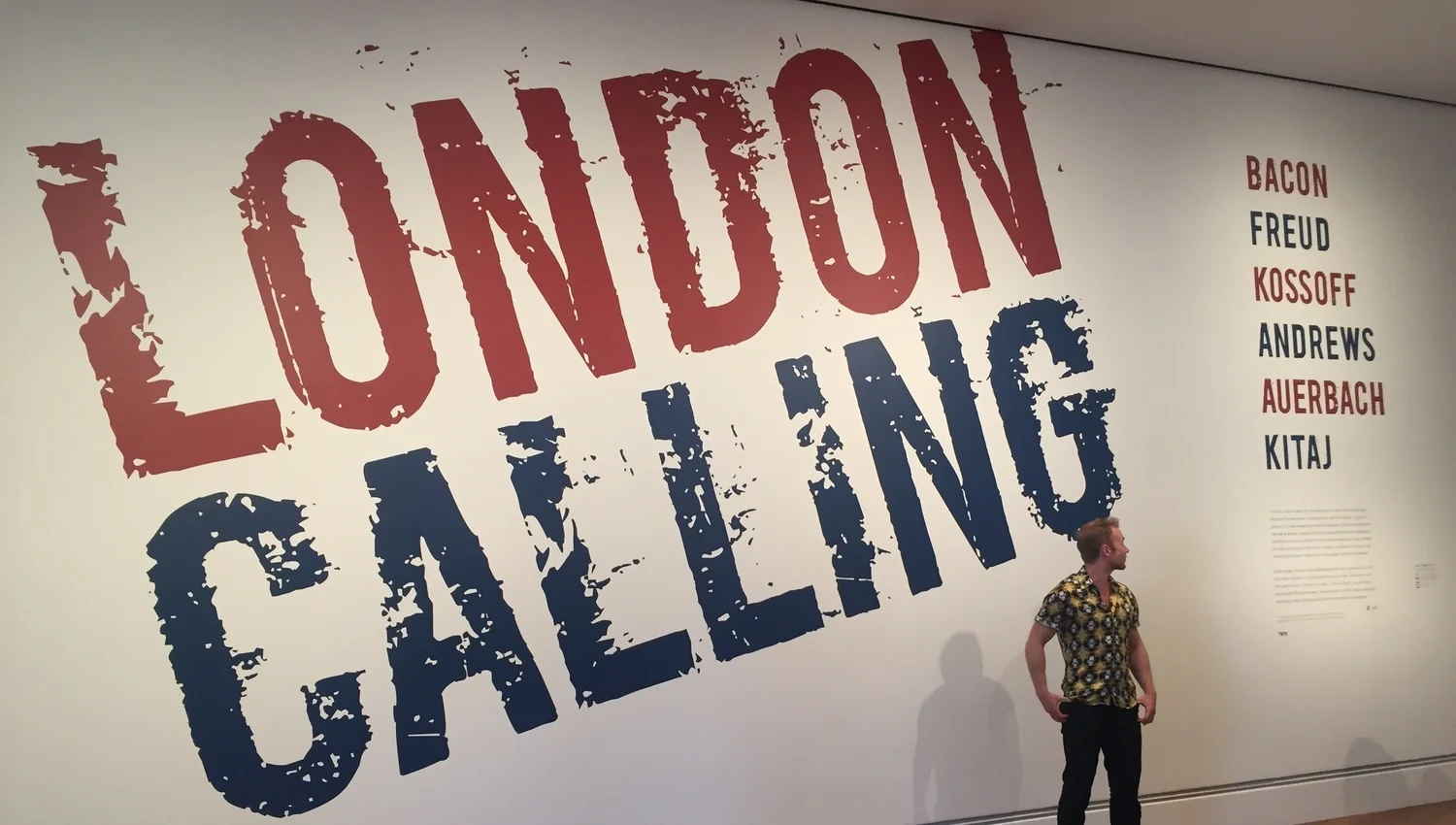

Why do we find sexuality a taboo subject in our culture? It is what creates life and yet can be a destructive force for many, a primordial unity for others and for all there is an element of sacrifice. The French call it La Petite Mort (The Little Death), Marcelle Hanselaar's series of etchings by this name have been were an early influence on me. I feel much of life comes down to this tiny demise, figurative painting by the London School in particular Bacon and Freud capture this so well.

Each relationship is structured differently and for conventional morality to get in the way of others happiness is ludicrous. For instance, it’s hard to believe not so long ago Homosexuality was not allowed, in fact it was illegal, as Francis Bacon’s work vividly demonstrates, during the creation of Reclining Woman 1961 (on display in this exhibition) the figure was suppose to be male, presumably his lover at the time, and in order to not be found out for his crimes he painted over the penis to make the figure appear female. This was the case with a number of his portraits up until the Sexual Offenses Act of 1967 allowed homosexual relationships in private. These works offer some exposure, revealing some things that are strange and difficult in our nature, yet I believe need to be explored to have lived fully.

Bacon is so present in all his paintings, the canvas and the subject are reflections of himself, there is no distance between himself and the painting. The same could be said of his lovers, his willingness to express a violent space even in the most casual ways is not an intimidation, but an invitation. He wanted to instigate the other, his way of seduction.

Though since Sigmund Freud the revelation that a person's sexuality informs so much about their behavior, the sexuality of Freud and Bacon standing in parallel opposition to each other, respectively extreme cases of both, Freud having potentially fathered 54 children (though only 14 of them confirmed publicly). Says something very fundamental about the way they see their subjects. For Freud he is like the observer, with a penetrating eye wishing to see his subject at their most vulnerable, to deeply understand them for the individuals they are. For Bacon he wishes to inspire his subjects for them to fight back at him, Freud wishing to subdue his subject.

"It's true to say when you paint anything you are also painting not only the subject but you are also painting yourself as well as the object that your trying to record" - Francis Bacon

There is, I feel, in my father Peter Fuller's perception of Bacon a fear of the humiliation of his gaze, and to meet Bacon would in itself be a violent act without any physical manifestations taking place. The mutilation that would occur in the mind alone would be enough to warrant a skepticism of his work. My father saw a threat in Bacon's pictures, that he thought only a concern with the grotesque could entertain. And he walked with this weight, the underlying value that their cannot be dignity in roughness. I don't believe roughness should be shied away from, but wholly embraced in order to fully live.

"I've always hoped to put over things as directly and rawly as I possibly can" - Francis Bacon

Here is where me and my father differ, on painters like Bacon, roughness, adrenaline, immediacy are all vital parts to an actors craft. An actor has only their humanity to bear, it's all they have to offer, even in the flesh, skin deep, blood flowing moment the actor finds their true self and that is what they bring to the world. Immediacy and sponteity are key aspects to Bacon's work. In acting there is a necessary ugliness, not in order to shock but in order to reveal, the best actors are emotionally naked, they've put themselves bare faced onto the world's stage, their ideas, their feelings and their unique individual song and if they've stayed the course they've been subject to all the ridicule the Western world has to offer in its competitive nature and still they stand in front of the camera lens, brave and naked. Daniel Day-Lewis said that it is "very hard to have any dignity as an actor" though he has tried for both, and in contradiction has revealed his soul through the life of another. There's this idea that actors are like meat puppets or narcissists, and all that they say is in order to sell themselves, and yes indeed the profession does attract many people like this, but the truly great actors know that there is not enough of their own humanity to bear to fill the void of the swelling mob as they seek love in another, and humility in the face of this is their only option, a constant, unending sacrifice of dignity, all the while struggling to pick it back up. I feel this same dichotomy is present in Bacon's pictures and in our relationship to sexuality.

Bacon said that he would to have liked to make some films towards the end of his life, painting solely from photographs and raw emotions, his subjects are reimagined first through a lens and then with the brush. American films are far more accepting of portrayals of violence, than they are depictions of sexuality, the naked human form is judged far more harshly by the censors than that same form being blown to bits by a machine gun. I believe that this is a mistake in our culture.

In the famous interview between David Sylvester and Francis Bacon, Sylvester suggests that Hockney is the antithesis of Bacon. And if as I have suggested in the past London based expressionist artist Marcelle Hanselaar is in line with Bacon, certainly one that that they share is this sense of theatricality in their work. I remember talking to Marcelle Hanselaar in this interview about the comparisons between theatre and painting. When I asked Marcelle 'Do you think shocking images will captivate people more?' she responded "I think because an image is artificial what you do on a canvas, you try to grab a whole life or a whole situation really on a square or rectangular piece. So of course it's like theatre you have to dramatize it, it has to be intensified, because otherwise people for the same money will just look at the wall and think 'nice wallpaper'". We discussed how in the mise-en-scène, the situation which we find her characters there is quite often a social dynamic wether its a lone figure caught in the act of something or multiple figures and they are caught, Marcelle told me that this sense of theatricality comes from a need to create an immediacy in her work, something Bacon was continually concerned with.

Yet there is a decided difference between what Bacon and Hanselaar call immediacy and theatricality, and the kind that Hockney puts to use in his work. It's much the same subjective approached from completely different corners.

An actor friend told me recently that I maintain a kind of stoic position to life in spite of it all, I feel in full consideration of the moment of death it becomes very difficult not to value the preciousness of life. "It is not death that a man should fear, but he should fear never beginning to live” - Marcus Aurelius. Bacon had much the same outlook when he suggested to David Sylvester that life life is so much sweeter to this who walk in the shadow of death because it can be taken away at any moment.

My father, who defended the preciousness of life, would constantly tell his friends that he was going to die young and would go about his work leaving the legacy that he did by the age of 42, with a kind of franticness, which is now recited back to me by those same friends as an ironic part of his story. I believe this stoic awareness of death was a vital aspect to his point of view on art. Though in the case of Bacon he defended the dignity of the image by bearing his own demons on paper and allowing the images to speak to the most vulnerable parts of ourselves, therefore he had a difficult relationship to Bacon's paintings:

RAW BACON

by Peter Fuller

Their heads are eyeless and tiny. Their mouths, huge. Two of them are baring their teeth. All have long, stalk-like necks. The one on the left, hunched on a table, has the sacked torso of a mutilated woman; the body of the centre creature is more like an inflated abdomen propped up on flamingo legs behind an empty pedestal; the third could be a cross between a lion and an ox: its single front leg disappears into a patch of scrawny grass.

They exude a sense of nature’s errors; errors caused by some unspeakable genetic pollution, embroidered with physical wound ing. One has a white bandage where its eyes might have been. All are an ominous grey, tinted with fleshly pinks: they are set off against backgrounds of garish orange containing suggestions of unspecified architectural spaces.

Francis Bacon painted this triptych, Three Studies for Figures at the Base o f a Crucifixion, now in the Tate Gallery, in 1944. It was first exhibited at the Lefevre Gallery the following April, where it hung alongside works by Moore, Sutherland and others who had sought to redeem the horrors of war through the consolations of art. Although Bacon referred to traditional religious iconography, he did not wish to console anyone about anything. Indeed, he seemed to want to rub the nose of the dog of history in its own excrement.

When the Three Studies was first shown, the war was ending and it was spring. Bacon was out of tune with the mood of his times. Certainly, as far as the fashionable movements in art were concerned, he was to remain so. And yet his star steadily ascended. By the late 1950s he was one of an elite handful of ‘distinguished British artists’. Today his stature among contem porary painters seems unassailable. And yet Bacon - who recently held an exhibition of new work at Marlborough Fine Art to mark the publication by Phaidon of a major monograph, Francis Bacon, by Michel Leiris - must be the most difficult of all living painters to evaluate justly. His work is so extreme it seems to demand an equally extreme response.

Bacon has always denied that he set out to emphasise horror or violence. In a chilling series of interviews conducted by David Sylvester, he qualified this by saying, ‘I’ve always hoped to put over things as directly and rawly as I possibly can, and perhaps, if a thing comes across directly, people feel that that is horrific.’ He explained that people ‘tend to be offended by facts, or what used to be called truth.’ He has repeatedly said that his work has no message, meaning or statement to make beyond the revelation of that naked truth.

Bacon’s serious critics have largely gone along with his own view of his painting. Michel Leiris, a personal friend of the painter’s, is no exception; Leiris argues that Bacon presents us with a radically demystified art, ‘cleansed both of its religious halo and its moral dimension’. Again and again, Leiris calls Bacon a ‘realist’, who strips down the thing he is looking at in a way which retains ‘only its naked reality’. He echoes Bacon himself in arguing that his pictures have no hidden depths and call for no interpreta tion ‘other than the apprehension of what is immediately visible’.

No doubt the ‘horror’ has been overdone in popular and journalistic responses to Bacon. But it is just as naive to think Bacon is simply recording visual facts, let alone transcribing ‘truth’. Creatures like those depicted in Three Studies can no more be observed slouching around London streets than haloes can be seen above the heads of good men, or angels in our skies. Of course Bacon’s violent imagination distorts what he sees.

But the clash between Bacon’s supporters and the populists cannot be dismissed as easily as that. The point remains whether Bacon’s distortions are indeed revelatory of a significant truth about men and women beyond the facts of their appearances; or whether they are simply a horrible assault upon our image of ourselves and each other, pursued for sensationalist effects. And this, whether Bacon and his friends like it or not, involves us in questions of interpretation, value and meaning.

The stature of Bacon’s achievement from the most unpropitious beginnings is not to be denied. Although his father named his only son after their ancestor, the Elizabethan philosopher of sweet reason, he was himself an unreasonable and tyrannical man, a racehorse trainer by profession. Nonetheless, Francis, a sickly and asthmatic child, felt sexually attracted to him. Francis received no conventional schooling and left home at sixteen, following an incident in which he was discovered trying on his mother’s clothes.

He worked in menial jobs before briefly visiting Berlin and Paris in the late 1920s; soon after, he began painting and drawing, at first without real commitment, direction or success. In the early 1930s, he was better known as a derivative designer of modern rugs and furniture, although an early Crucifixion, in oils, was reproduced by Herbert Read in Art Now. Bacon subsequently destroyed almost all his early work; his public career thus effec tively began only with the exhibition of Three Studies in 1944.

Bacon then began to produce the paintings for which he has become famous: at first there were some figures in a landscape; but soon he moved definitively indoors. He displayed splayed bodies, surrounded by tubular furniture of the kind he had once designed, in silent interiors. A fascination with the crucifix and triptych format continued; but he painted the naked, human body - usually male - in all sorts of situations of struggle, suffering and embuggerment. A picture of two naked figures wrestling on a bed of 1953 is surely among his best. But a series of variations on Velazquez’s Portrait o f Pope Innocent X - which he now regrets - became among his most celebrated. By the 1960s, the echoes of religious iconography and the Grand Tradition of painting had become more muted. Bacon could never be accused of ‘intimism’ : ‘homeliness’ is one of the qualities he hates most. The large, bloody, set-piece interiors continued; but the forms of their figures became less energetic, more statuesque. Bacon seemed increasingly preoccupied with portraits, usually in a triptych format, of his friends and associates: Isabel Rawsthorne, Henrietta Moraes, Lucian Freud, George Dyer (his lover), Muriel Belcher, the owner of a drinking club in Soho he frequented, and himself.

Bacon has repeatedly said that he is not an ‘expressionist’; it is easy to show what he means by this by contrasting his work with that of the currently fashionable, but lesser, painter George Baselitz (at the Whitechapel Gallery) - who is. Baselitz deals with a similar subject matter; but he invariably handles paint in an ‘abstract expressionist’ manner; i.e. in a way which refers not so much to his subjects as to his own activity and sentiments as an artist. Anatomy, physiognomy, gesture and the composition of an architectural illusion of space mean nothing to him: to Bacon, they are everything. Or rather almost everything.

For if he has sought to work in continuity with the High Art of the past, Bacon recognises that the painter, today, is in fact in a very different position. He has regretted the absence of a ‘valid myth’ within which to work: ‘When you’re outside tradition, as every artist is today, one can only want to record one’s own feelings about certain situations as closely to one’s nervous system as one possibly can.’

He stresses that the echoes of religion in his pictures are intended to evoke no residue of spiritual values; Bacon is a man for whom Cimabue’s great Crucifixion is no more than an image of ‘a worm crawling down the cross’. He is interested in the crucifix for the same reason he is fascinated by meat and slaught erhouses; and also for its compositional possibilities: ‘The central figure of Christ is raised into a very pronounced and isolated position, which gives it, from a formal point of view, greater possibilities than having all the different figures placed on the same level. The alteration of level is, from my point of view, very important.’ But, for Bacon, the myths of vicarious sacrifice, incarnation, redemption, resurrection, salvation and victory over death mean nothing - even as consoling illusions.

The appeal to a meaningful religious iconography is, in effect, replaced in his work by an appeal to photography; similarly, in his pictures, as in his life, the myth of a jealous and omnipotent god has been replaced by the arbitrary operations of chance.

Bacon’s fascination with Muybridge’s sequential photographs of men, women and animals in motion is well-known. References to specific Muybridge images are often discernible in his pictures; even his triptych format seems to relate more to them than to traditional altarpieces. He seems to believe that Muybridge ex posed the illusions of art, and freed it from the need to construct such illusions in the future. Unlike many who reached similar conclusions, they did not, of course, lead Bacon to narrow aestheticism or abstraction. Rather, he sometimes insists that the artist should become even more ‘realist’ than the photographer, by getting yet closer to the object; and, at others, that as a result of photography’s annexation of appearance, good art today has become just a game.

But this insistence on ‘realism’, and reduction of art to its ludic and aleatory aspects, are not, in Bacon’s philosophy, necessarily opposed. Accident and chance play a central role in his pursuit of ‘realistic’ images of men; they enter into his painting technique through his reliance on throwing and splattering. In fact, of course, Bacon exercises a consummate control over the effects chance gives him; but, as he once said, ‘I want a very ordered

image, but I want it to come about by chance.’ He fantasizes about the creation of a masterpiece by means of accident. The religious artists of the High Tradition attributed their ‘inspiration’ to impersonal agencies, like the muses or gods; and Bacon, too, is possessed of an overwhelming need to locate the origins of his own imaginative activity outside of himself.

The role of photography and chance in his creative process relate immediately to the view of man he is seeking to realise. ‘Man,’ he has said, ‘now realizes that he is an accident, that he is a completely futile being, that he has to play out the game without reason.’ Thus, in reducing itself to ‘a game by which man distracts himself’ (rather than a purveyor of moral or spiritual values) art more accurately reflects the human situation even than photo graphy . . . The human situation, that is, as seen by Bacon.

Bacon then has achieved something quite extraordinary. He has used the shell of the High Tradition of European painting to express, in form as much as in content, a view of man which is utterly at odds with everything that tradition proclaims and affirms. Moreover, it must be admitted that he has done so to compelling effect. It is perfectly possible to fault Bacon, technical ly and formally: he has a tendency to ‘fill-in’ his backgrounds with bland expanses of colour; recently, he has not always proved able to escape the trap of self-parody, leading to mannerism and stereotyping of some of his forms. But these are quibbles. Bacon, in interviews, has good reason constantly to refer back to the formal aspects of his work; he is indeed the master of them.

But this cannot be the end of the matter in our evaluation of him. Leiris maintains his ‘realism’ lies in his image of ‘man dispossessed of any durable paradise . . . able to contemplate himself clear-sightedly’. But is it ‘realistic’ to have a Baconian vision of man closer to that of a side of streaky pig’s meat, skewered at random, than to anything envisaged by his rational ancestor?

Nor can we evade the fact that Bacon’s view of man is con sonant with the way he lives his life. He emerges from his many interviews as a man with no religious beliefs, no secular ethical values, no faith in human relationships, and no meaningful social or political values either. ‘All life,’ he says, ‘is completely artificial, but I think that what is called social justice makes it more pointlessly artificial . . . Who remembers or cares about a happy society?’ One may sympathise with Bacon because death wiped out so many of his significant relationships; but his life seems to have been dedicated to futility and chance. It has been said that, for him, the inner city is a ‘sexual gymnasium’. He is obsessed with roulette, and the milieu of Soho drinking clubs. He wants to live in ‘gilded squalor’ in a state of ‘exhilarated despair’. He is not so much honest as appallingly frank about his overwhelming ‘greed’.

And it is, of course, just such a view of man which Bacon made so powerfully real through his painterly skills. Because he refuses the ‘expressionist’ option, he also relinquishes that ‘redemption through form’ which characterises Soutine’s carcasses of beef, or Rouault’s prostitutes. But it may, nonetheless, be that there is something more to life than the spasmodic activities of perverse hunks of meat in closed rooms. And perhaps, even if the gods are dead, there are secular values more profound and worthwhile than the random decisions of the roulette wheel.

I believe there are; and so I cannot accept Bacon as the great realist of our time. He is a good painter: he is arguably the nearest to a great one to have emerged in Britain since the last war. (Though I believe Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff are better.) Nonetheless, in the end, I find the vision of man he uses his undeniable painterly talents to express quite odious. We are not

mere victims of chance; we possess imagination - or the capacity to conceive of the world other than the way it is. We also have powers of moral choice, and relatively effective action, whether or not we believe in God. And so I turn away from Bacon’s work with a sense of disgust, and relief: relief that it gives us neither the ‘facts’ nor the necessary ‘truth’ about our condition.

1983

Why do we find sexuality a taboo subject in our culture? It is what creates life and yet can be a destructive force for many, a primordial unity for others and for all there is an element of sacrifice. The French call it La Petite Mort (The Little Death), Marcelle Hanselaar's series of etchings by this name have been were an early influence on me. I feel much of life comes down to this tiny demise, figurative painting by the London School in particular Bacon and Freud capture this so well.